Download this updated report[*] (Updated September 2021; 20 pages; pdf)

Download the original report (March 2021; 20 pages; pdf)

Introduction

All children need access to nutritious food in order to be healthy. Food security – having reliable access to adequate amounts of nutritious food – is a social determinant for both physical and mental health, and children with consistent access to fresh produce perform better in school and are better equipped to meet developmental milestones, helping them build a strong foundation for future success. Unfortunately, the high rates of food insecurity in New Mexico prevent many children from reaching their full potential. The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened child food insecurity, making it more urgent than ever to take immediate action on this issue.

Definitions

Food Insecurity: Limited or uncertain access to adequate food for an active, healthy life due to lack of money and other resources.[1]

Hunger: A potential consequence of food insecurity that, because of prolonged, involuntary lack of food, results in discomfort, illness, weakness, or pain that goes beyond the usual uneasy sensation.[2]

Food Desert: Geographic area at least 1 mile (in urban settings) or 10 miles (in rural settings) from the nearest supermarket or large grocery store.[3]

-McKinley County community member

Evidence-based programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and tax credits like New Mexico’s Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC) and Low-Income Comprehensive Tax Rebate (LICTR), help New Mexicans gain financial security and address the root causes of food insecurity. However, when there are barriers to accessing these programs, or when they are underfunded, many families are forced to choose between healthy food and other basic household needs. By taking a holistic approach to solving the joint epidemics of financial and food insecurity, we can ensure that all New Mexico families have reliable access to nutritious food during the pandemic and beyond.

Food Insecurity in New Mexico

New Mexico has long had one of the worst rates of child food insecurity in the country. In 2020, 26% of New Mexico children experienced food insecurity,[4] which is up from pre-COVID-19 levels of 22%. Due to COVID-19, food insecurity in one county was as high as 38% in 2020 (see Figure I).

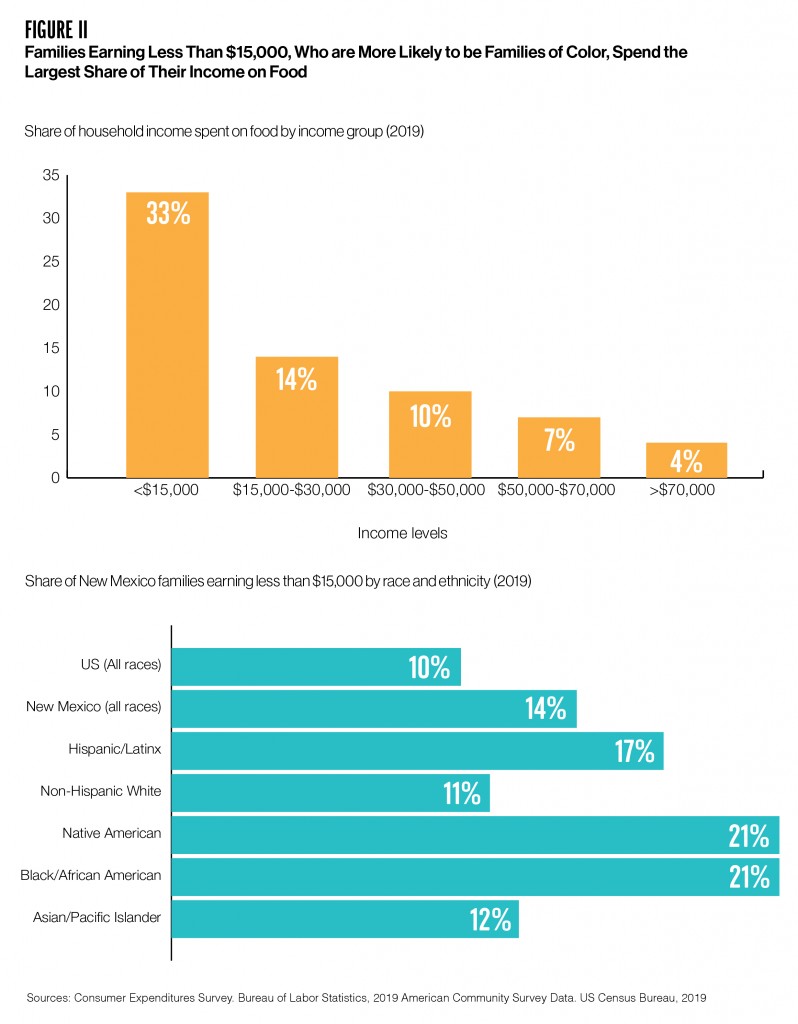

Food insecurity, which is defined as limited or uncertain access to food,[5] is most prevalent among families of color and those living in food deserts or poverty – meaning a household income of less than $25,750 a year for a family of four. In 2019, 25% of New Mexico children lived in poverty, which is the third highest rate in the country.[6] Children ages 0 to 3 experienced even higher rates of poverty at 36%, compared to 24% nationally.[7] Poverty is a major determinant of food insecurity because lower-income families often have to make trade-offs between purchasing food and other basic needs since food costs make up a larger share of their household budget. New Mexico households with annual income of less than $15,000 – which are disproportionately Black, Native American, and Hispanic – spend on average 33% of their income on food compared to 4% for households earning more than $70,000[8] (see Figure II).

Food insecurity, which is defined as limited or uncertain access to food,[5] is most prevalent among families of color and those living in food deserts or poverty – meaning a household income of less than $25,750 a year for a family of four. In 2019, 25% of New Mexico children lived in poverty, which is the third highest rate in the country.[6] Children ages 0 to 3 experienced even higher rates of poverty at 36%, compared to 24% nationally.[7] Poverty is a major determinant of food insecurity because lower-income families often have to make trade-offs between purchasing food and other basic needs since food costs make up a larger share of their household budget. New Mexico households with annual income of less than $15,000 – which are disproportionately Black, Native American, and Hispanic – spend on average 33% of their income on food compared to 4% for households earning more than $70,000[8] (see Figure II).

SNAP usage, which can be considered a proxy for measuring food insecurity, also reveals disparities by race and ethnicity (see Figure III). Because SNAP is supplemental, benefits do not provide all of the food a family needs over the course of a month, so families receiving SNAP benefits may still be food insecure.

SNAP usage, which can be considered a proxy for measuring food insecurity, also reveals disparities by race and ethnicity (see Figure III). Because SNAP is supplemental, benefits do not provide all of the food a family needs over the course of a month, so families receiving SNAP benefits may still be food insecure.

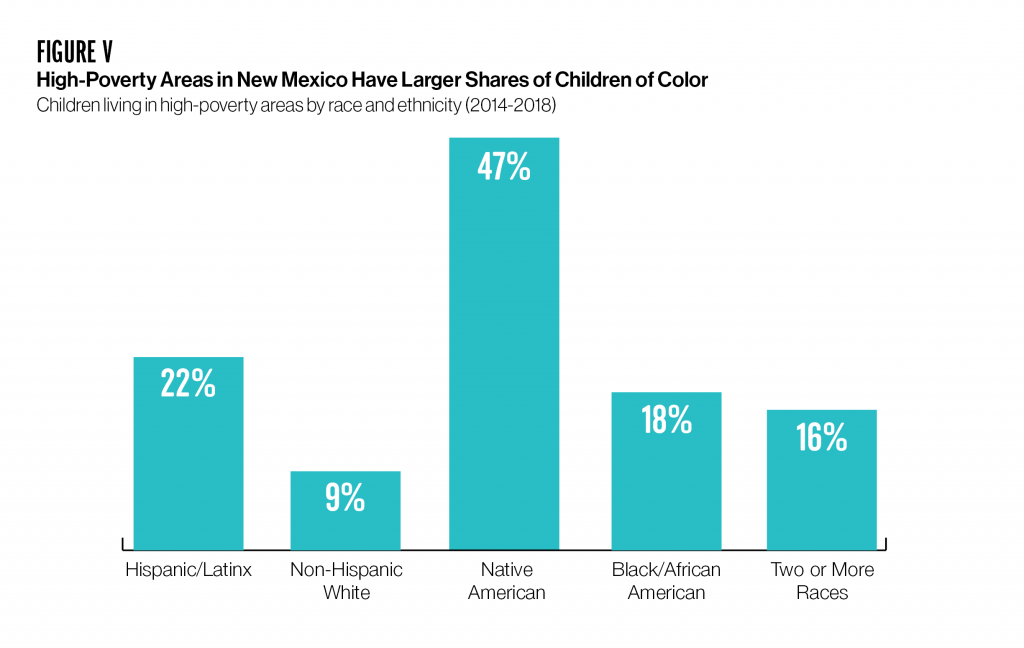

Although the full consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic remain to be seen, it is already clear that communities of color have been hit the hardest.[9] This public health crisis and recession are likely to worsen long-standing disparities in poverty rates between different racial and ethnic groups in New Mexico. Before the pandemic, Native American children had disproportionately higher rates of poverty (41%) compared to non-Hispanic white children (14%).[10] This income inequity contributes to racial and ethnic disparities in food insecurity. In 2018, 24% of Hispanic households and 17% of Black households experienced food insecurity. Native American households experienced the highest rate at 27% while non-Hispanic white households had the lowest rate at 10%.[11] In McKinley County, for example, where the population is 75% Native American, 37% of children experienced food insecurity in 2020, almost twice the national average (20%).[12] The high rate of food insecurity among Native American communities stems from a multitude of factors including a long history of structural inequities, systemic racism, and the theft of the lands where their ancestors grew and hunted food that stripped tribal people of their food sovereignty. Furthermore, large COVID-19 outbreaks in counties with majority Native American populations have exacerbated food insecurity in many communities that already experienced high rates.[13]

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a dramatic increase in demand for emergency food support from organizations such as food banks,[14] and upwards of 14% of New Mexican households with children report needing help securing food.[15] This increased demand has strained the emergency food system, particularly in rural areas and food deserts, which already face numerous difficulties in food access. Nearly 30% of New Mexicans live in a food desert,[16] meaning they live either 1 mile (in urban settings) or 10 miles (in rural settings) from the nearest supermarket or large grocery store (see Figure IV).

Limited access to nutritious food and fresh produce is a significant barrier to healthy dietary choices for rural and frontier communities in particular. Grocery stores in rural areas often lack fresh produce and families end up depending on lower-quality processed foods and unhealthy junk foods for subsistence. Additionally, inadequate rural transportation infrastructure disproportionately impacts New Mexico’s Native American communities. Poorly maintained roads and the absence of public transportation can make it difficult to get to the store and even impossible during bad weather.[17] To complicate matters more, the lack of cold storage in these areas severely limits the ability of the emergency food support system (e.g. food banks and school feeding programs) to provide these communities with fresh and healthy food.

New Mexico’s immigrant communities have faced many threats to food security, in part due to numerous attacks by the Trump Administration. The ‘public charge’ rule change penalized the use of safety net programs including SNAP, Medicaid, and Section 8 housing for some non-citizens who have historically been eligible for them. Even though the public charge rule change was reversed, it had already resulted in serious consequences for immigrant families. Once the public charge rule change was announced, non-citizens, as well as their citizen family members, reported avoiding enrolling in SNAP out of fear of deportation.[18] This ‘chilling effect,’ coupled with the exclusion of many immigrants from federal COVID-19 pandemic relief,[19] likely worsened food insecurity in immigrant communities. While no region-specific data are available on food insecurity among New Mexico’s immigrant and refugee communities, foreign-born Hispanics nationwide have higher rates of food insecurity than do U.S.-born Hispanics.[20]

Hunger and food insecurity among students in higher education is often overlooked, in part due to preconceived notions about college students coming from better-resourced families. In fact, as of 2018, 26% of undergraduate students were in households earning incomes at or below the poverty line.[21] More than 70% of college students were non-traditional, meaning they are financially independent from their parents. Non-traditional students likely started college late, may be a caregiver, and may maintain a job outside of school.[22] A recent survey of undergraduate students at the University of New Mexico found that 37% of respondents had experienced food insecurity within the past 30 days.[23] Some national data on college food insecurity during the pandemic shows that rates are even higher for community college students. In addition, Black students experience food insecurity at rates 19% higher than do white students.[24] The federal SNAP regulations restrict college students from accessing SNAP, based on the assumption that many are financially dependent on their parents. There are some exemptions for this rule including: students who are parents of young children, work more than 20 hours a week, or are enrolled in employment and training programs. Unfortunately, up to 18% of New Mexico’s college students may be eligible for SNAP but only 6% are enrolled, meaning the state is missing out on more than $22 million in federal resources to help address student hunger.[25]

-Albuquerque community member

Food Insecurity and Population Health

Food insecurity takes many forms and not everyone who is food insecure experiences hunger. Some households report having to skip meals whereas others depend on calorie-dense and lower-quality foods that do not satisfy basic nutritional requirements. Regardless of the reason, the consequences of childhood food insecurity follow a person over their lifetime. Children who experience even a marginal level of household food insecurity are more likely to develop behavioral, academic, and emotional problems.[26] Parents report that the frustration, anxiety, and depression caused by food insecurity negatively impacts their children’s physical and mental health, contributing to behavioral problems at school.[27] Children in households experiencing food insecurity are at a higher risk of impaired cognitive and physical development than are those in food-secure households.[28]

Cheaper foods and those with processed grains, fats, and sugars are associated with higher rates of childhood obesity and diabetes.[29],[30] Therefore, children in food-insecure households are also at a higher risk of being overweight and having diabetes, in part due to overconsumption of calorie-dense, nutritionally poor foods.[31],[32] A recent study found that adults who experienced food insecurity as children had higher rates of lifetime chronic health conditions such as asthma and depression, and are more likely to forgo necessary medical care.[33] These higher rates of chronic conditions increase health care costs, perpetuating the cycle of poverty by adding a significant financial burden on families already experiencing material hardship. Food insecurity ends up costing, on average, $1,914 in excess medical costs each year for an individual.[34] Obesity is associated with an increased risk of lifelong chronic illness management that can amount to more than $150,000 in excess medical costs over a lifetime.[35]

-McKinley County community member

Food Spending and Food Choices

Money and time are both barriers to families trying to make healthy food choices. Fresh, nutritious foods take more time to prepare and are generally more expensive than processed foods, which can make them impractical choices for low-income families. Those facing cost constraints purchase less fresh produce and lean meats. In New Mexico, 79% of children and 83% of adults are not eating enough fruits and vegetables[36] (Figure VI). In addition, parents in food-insecure households may have trouble affording foods that are culturally appropriate or that align with dietary restrictions or food allergies.

Current Programs

Federal- and state-level public assistance programs such as TANF and SNAP, tax credits, and other income supports have been shown to increase spending on food and decrease food insecurity.[37],[38],[39] Food pantries are also a valuable resource for filling in some of the meal gaps faced by low-income families and can help supplement public assistance programs. Unfortunately, even accounting for public assistance and food pantries, it is estimated that low-income New Mexicans still miss 13% of their meals – or three meals a week.[40]

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

SNAP – what used to be called food stamps – is a highly effective program aimed at reducing food insecurity by increasing the recipient’s spending power on food, which then indirectly allows for increases in spending on housing, education, and transportation, and offsets other forms of material and financial hardship that families earning low incomes face. New Mexico has the largest share of residents enrolled in SNAP (21.1%) in the nation.[41]

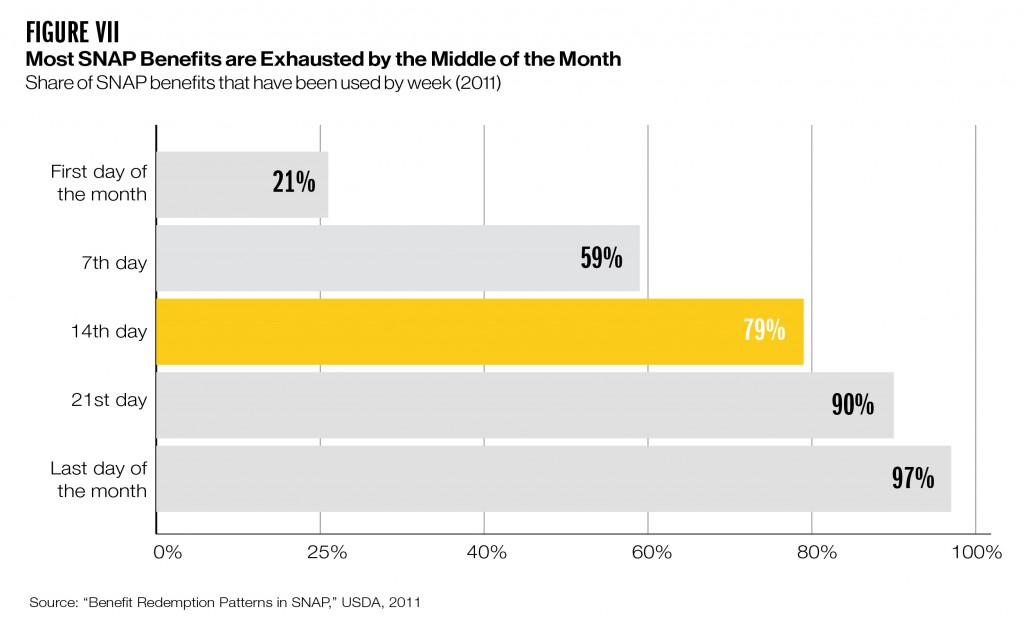

The benefits of SNAP participation on the health and well-being of its recipients are well documented. SNAP benefits have been shown to improve math and reading scores for children in kindergarten through third grade,[42] and SNAP enrollment is associated with not having to repeat grades.[43] Early childhood access to SNAP promotes healthy developmental and cognitive outcomes, thereby improving performance at school, increasing economic mobility, and decreasing the risk of chronic disease.[44],[45],[46] Unfortunately, SNAP benefit amounts are often too low to empower families to make the healthiest food choices. SNAP benefit amounts are based on the USDA’s “Thrifty Food Plan” that expects most meals to be prepared from scratch, requiring up to 8 hours more per week than the average amount of time families spend preparing meals,[47] an unrealistic expectation for working families. And, because they are “supplemental,” SNAP benefits do not meet a family’s entire food needs. Typically, 80% of SNAP benefits are used up within the first half of the month[48] (see Figure VII).

Towards the end of the benefit cycle, SNAP-receiving families are often forced to make a choice between food and other basic necessities meaning they eat less, have a lower quality of diet, and experience more food insecurity and hunger.[49] More than 60% of New Mexico families with low food security report having to make the choice between paying utilities and buying food[50] (see Figure VIII).

Towards the end of the benefit cycle, SNAP-receiving families are often forced to make a choice between food and other basic necessities meaning they eat less, have a lower quality of diet, and experience more food insecurity and hunger.[49] More than 60% of New Mexico families with low food security report having to make the choice between paying utilities and buying food[50] (see Figure VIII).

As part of the federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act, New Mexico was able to increase benefit amounts for all SNAP recipients up to the maximum amount available based on the size of their household.[51] While this move helped many low-income households who were receiving less than the maximum amount of SNAP benefits, it did nothing to help the lowest-income households already receiving the maximum amounts.

Food Banks

There is a network of five food banks that provide emergency food relief for families throughout New Mexico. Many food-insecure New Mexico families do not qualify for federal nutrition programs, which can be due to factors such as immigration status or household income, so they depend on local food banks for support. Food banks have always had an important role in improving food security. Before the pandemic, the largest food bank in the state, Roadrunner Food Bank, provided food for 70,000 New Mexicans each week.[52] The pandemic increased the demand for emergency food relief and from March through April of 2020, the two largest food banks in New Mexico spent $1.65 million purchasing food for New Mexicans in need.[53]

School Meals

The federal school meals program is a highly effective option for ensuring school-age children have access to nutritious food. In New Mexico, 75% of students participate in the free and reduced-price school lunch program.[54] Meals during the school day are essential for students living in severely food insecure households and, for some, may be the only regular meals they receive. When schools transitioned to remote learning because of COVID-19, students participating in these programs had difficulty accessing school meals. As a result, many school districts throughout the state provided grab-and-go meals, typically making them available to all students regardless of school meal program eligibility. Families with students who receive free or reduced-price school meals could also participate in the Pandemic-EBT program, where families received SNAP benefits as a replacement for missed school meals.[55] Continuing to offer school meals or expanding access to them if schools go back to virtual or hybrid classes will require increasing and maximizing funding and leveraging the infrastructure of the school system.

Double Up Food Bucks (DUFB)

The state-funded DUFB program, operated by the New Mexico Farmers’ Marketing Association, doubles the spending power for SNAP recipients by matching SNAP benefits dollar-for-dollar when spent on fresh produce grown locally. The DUFB program is available at 80 locations across New Mexico including 41 farmers markets, but also some grocery stores, farm stands, community-supported agriculture, and mobile markets, which makes it easier for New Mexicans in rural communities to access healthy food. In 2018, SNAP recipients in New Mexico spent more than $1 million in combined SNAP and DUFB, a nearly three-fold increase from $354,000 in 2015.[56] Of the DUFB participants, 75% said their families are eating more fruits and vegetables and 57% are eating less junk food. By incentivizing SNAP spending on fresh produce at farmers’ markets, more families have access to healthy food, making New Mexico healthier while supporting small, local growers. As a result of DUFB, three out of four participating farmers report making more money and more than a quarter plan to hire new staff. Programs like DUFB connect consumers to a network of local producers, strengthening the local food system and economy.

Heat and Eat

Federal law allows families who receive at least $20 a month in energy assistance an increase in their SNAP benefits. This is known informally as the “Heat and Eat” program. States can provide this energy assistance through the federally funded Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). However, LIHEAP is only available to families who pay a heating or cooling bill separately from their rent. This leaves many New Mexicans whose utilities are included in their rent ineligible for the increased SNAP benefits afforded by Heat and Eat.

Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP)

The CACFP reimburses the costs of meals for eligible children in community-based child care programs including child care centers, day care homes, Head Start programs, family child care homes, after-school care programs, and emergency shelters. This funding addresses food insecurity for young children at a critical time for brain development, promoting better cognitive and health outcomes.[57] However, New Mexico’s participation in this program has fallen dramatically putting us behind the rest of the country. In 2018, only 7,890 New Mexico children participated in CACFP in home child care settings.[58] This represents a 40% drop from 2013, compared to a 9% drop nationally. Among child care centers, CACFP participation in New Mexico increased by only 19%, compared to a 36% increase nationally during this time frame.

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

Federally funded TANF is a critical, but underutilized and underfunded anti-poverty program that provides cash assistance to families with children who earn very low incomes or are between jobs. Cash assistance helps parents afford basic household needs including diapers, clothing, and housing, allowing families to spend more money on food. Cash assistance is one of the most effective ways to eliminate child poverty, according to a recent National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine report.[59]

Progress from the Regular 2020 Legislative Session

Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham has made ending child food insecurity a high priority. In working toward this end, policymakers passed several pieces of legislation during the 2020 regular legislative session, including:

A State-level “Heat and Eat” Program was Created in Statute

By creating a state-funded energy assistance program during the 2020 regular session, legislators helped ensure all SNAP-eligible families could take advantage of the Heat and Eat benefit, regardless of whether they pay a separate heating/cooling bill. With a $1.5 million investment, the state will be providing energy assistance to 68,000 SNAP-eligible households – almost one-third of all SNAP households, about half of which have children – making these families eligible for up to $90 per month in increased SNAP benefits. Every SNAP dollar spent generates $1.70 in economic activity, circulating tens of millions of dollars through the local economy. By establishing this program in law, the state has ensured it will continue through successive administrations.

Co-pays were Eliminated for Reduced-price School Breakfast and Lunch

House Bill 10 appropriated almost $540,000 to the NM Public Education Department to eliminate co-pays for almost 12,500 students living at or below 185% of the federal poverty level. These small co-pays add up over the course of the school year and are a significant barrier for students’ access to school breakfast and lunch.

Funding was Increased for New Mexico Grown Fruits and Vegetables for School Meals Program

More than $330,000 was appropriated for the fiscal year 2021 budget. This funding went to the NM Public Education Department to expand the New Mexico Grown Fruits and Vegetables for School Meals Program, to increase the availability of fruits and vegetables for students while supporting local growers and food systems.

Funding was Increased for the TANF Transition Bonus Program

The NM Human Services Department received an appropriation of $1.8 million in federal funding for the TANF Transition Bonus Program, which provides $200 per month for up to 18 months for TANF participants who maintain at least 30 hours in paid employment per week. This program is meant to support parents in low-income families as they transition back into the workforce. Unfortunately, using federal funds makes the program difficult to administer and will likely result in a low participation rate due to the burdensome reporting requirements associated with federal funding.

Progress from the Regular 2021 Legislative Session

In response to the pandemic, New Mexico legislators increased and expanded two refundable tax credits, which are an evidence-based approach for ensuring that families have more money to spend on food and other household goods. This spending also supports local economies all around the state. These tax credits also improve health outcomes for parents, infants, and children, and children in families that receive them do better in school, are more likely to attend college, and earn more as adults, helping break the cycle of poverty.

The Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC) was Expanded and Increased

The WFTC is the state version of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which has long had bipartisan support in Congress. Legislators increased the WFTC from 17% to 20% of the EITC; ended the exclusion for tax filers using an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number, and ended the exclusion for young adult workers (ages 18-25) without children. Refundable tax credits have been shown to increase families’ purchases of healthier food options and they improve health outcomes, helping break the cycle of poverty.[60]

The Low-Income Comprehensive Tax Rebate (LICTR) was Increased and Indexed to Inflation

Families and seniors earning the least money pay a larger share of their incomes on certain state and local taxes, such as the gross receipts tax, than do those earning more money. LICTR was enacted to help rectify this. Until 2021, however, it had not been updated in more than two decades, meaning it was helping fewer and fewer of the people it was designed for, having lost much of its value due to inflation. In 2021 lawmakers expanded eligibility for LICTR and tripled the amount of the rebate. They also Indexed LICTR to inflation so it won’t lose its value over time.

Funding was Appropriated for Anti-Hunger Programs

In the budget, $2.72 million was appropriated to fund several K-12 school nutrition programs including: New Mexico Grown, which puts locally grown produce into schools; breakfast after the bell; and reducing co-pays for school meals. Another $100,000 was directed to initiate a pilot program to address college hunger. And $275,000 was appropriated to fund a committee of stakeholders from the government, industry, and the nonprofit sector to strategize how to make our food system more sustainable and locally based, with the goal of eliminating hunger and strengthening the local economy.

Post-Session Progress

Improvements were Made to the Child Care Assistance (CCA) Program

Most parents cannot work without child care and even fewer can afford high-quality care without some assistance. The lack of child care has significantly stalled our economic recovery, as it keeps many parents from returning to the workforce. Earlier this summer, the state’s Early Childhood Education and Care Department put federal American Rescue Plan Act funding to work by greatly expanding the state’s CCA program. Among the changes: eligibility was raised significantly, meaning most working parents will qualify for some assistance; co-payments were reduced; and reimbursement rates for providers were increased.

Policy Recommendations

Even in light of these victories, much more work needs to be done – particularly in the wake of the Covid delta surge, which hit after the 2021 regular session was over. Among our policy recommendations, we urge policymakers to:

Enact a State-level Child Tax Credit (CTC)

Increases in the federal CTC, which will benefit most families with children, coupled with the advance payments that began earlier this summer, are expected to dramatically reduce child poverty over the next year. New Mexico should also consider enacting a state-level CTC in order to help more families with children afford basic expenses like food, housing, and child care.

Increase the WFTC for Families with Young Children

While improvements were made to the WFTC in 2021, more could be done to help parents with children younger than 6 years. Parents with young children are generally young themselves, meaning they are just starting out and have not yet reached their peak earning years. Meanwhile, preschool-age children have specific needs – such as diapers, strollers, and other safety-related products – that are costly but that older children have out-grown. Boosting the credit amount for parents whose children are ages 0 to 5 would help ensure these families can better afford basic necessities.

Fully Fund Food Banks, Pantries, and School Meal Programs

More than ever, New Mexicans are depending on food assistance programs to meet their nutritional needs. This increased demand during the pandemic has put significant strain on these systems, which have had to adapt in order to provide critical food support for more New Mexicans. The state can help strengthen the food assistance system and promote food security throughout the pandemic and after by ensuring that food banks, food pantries, and school meal programs are fully funded.

Expand Double Up Food Bucks

Increasing funding for DUFB would expand these benefits for eligible New Mexicans while further developing New Mexico’s local food and farming systems. Increased funding could also support outreach in rural areas to build more awareness of the program, attract local producers to sell at retail outlets, and be used to hire staff to help relieve the administrative burden of the smaller markets that participate in DUFB. In addition to funding, SNAP recipient participation in DUFB could be further incentivized by including more grocery stores in the DUFB program. This would support a more extensive network of outlets for DUFB participants to choose from and allow families to take advantage of the program when farmers markets are not open or are out of season.

Increase the Visibility of SNAP Among College Students

Many college students aren’t aware that they may be SNAP-eligible. Increasing awareness through outreach would help normalize and reduce the stigma of SNAP recipiency for students in both 2- and 4-year degree programs. Institutions can do this by making materials and resources for enrolling in food and nutrition programs available to students during orientation and use information from the Free Application for Federal Student Aid forms to inform students about SNAP eligibility. States can also let school enrollment count towards SNAP work requirements, remove work requirements for full-time students, and develop criteria for institutions to be designated “hunger-free campuses.” Other steps include allowing SNAP purchases at on-campus retailers, and expanding on-campus food pantries, food recovery programs, or dining center meal donation programs.

Remove Work Requirements for TANF

The rate of TANF participation has dropped in large part due to work requirements enacted during the last recession. Unless work requirements are paired with programs that help families increase their skills and education, they ultimately do not improve workforce participation rates and instead are associated with increases in deep poverty.[61] New Mexico should remove the work requirements enacted in 2011, giving families more flexibility in accessing TANF benefits.

Increase TANF Benefits

As the primary cash assistance program for families living in poverty, the purpose of TANF is to help families meet basic needs. Unfortunately, TANF benefits are insufficient for accomplishing this purpose. In New Mexico, benefits amount to only $447 per month for a family of three, which equals a household income at 26% of the federal poverty level. The state’s TANF benefit has not been increased since 1996, therefore increasing the benefit amount and indexing it to inflation would make TANF benefits more impactful for its recipients. The state can also use TANF to provide diaper stipends for families with young children. Families spend $70 to $80 a month on diapers for each child, and state funding of $3 million would provide the almost 3,300 families on TANF with children ages 0 to 3 with a diaper stipend,[62] helping offset an unavoidable expense of raising children. Another update to TANF that would make the program more impactful includes implementing a full pass-through policy, which allows TANF recipients to retain 100% of the child support payments that the state collects on their behalf. Furthermore, eliminating TANF time limits will give families a better chance at having the support they need to achieve economic security.

Make the Improvements to Child Care Assistance (CCA) Permanent

In New Mexico, single-parent families spent roughly 40% of their monthly income on child care[63] before changes were made to CCA. New Mexico should make the improvements in child care permanent in order to continue to give families access to safe, healthy environments for their kids to grow and learn in while parents work.

Support Food Sovereignty for Tribal Communities

Policymakers should consult, learn from, and work directly with tribal governments and organizations – such as the Notah Begay III (NB3) Foundation and the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance – that promote food sovereignty for tribal communities. These groups have the most qualified experts on restoring New Mexico’s Native food systems with culturally appropriate, place-based food practices, natural resource management, and sustainable economic and infrastructural development. They need to be at the forefront of developing the policy solutions that will most effectively address food insecurity and food sovereignty in Native communities.

Keep Food Tax-Free

Taxing food is a regressive policy that would worsen inequities in food access by further straining the household budgets of food-insecure families. This policy would have broad consequences for public health by compromising financial security for many low-income New Mexicans.

Derek Lin, MPH, is a research and policy analyst with New Mexico Voices for Children

*Updated to include new data, legislation, and regulations, as well as to correct an error in data about children ages 0 to 3

Endnotes

[1] Definitions of Food Security, USDA ERS, 2020

[2] Ibid

[3] USDA Food Access Research Atlas, USDA, 2017

[4] “The Impact of Coronavirus on Food Insecurity,” Feeding America, 2020

[5] Definitions of Food Security, USDA ERS, 2020

[6] State of the States: Profiles of Hunger, Poverty, and Federal Nutrition Programs, Food Research & Action Center, 2020

[7] “Profile of Infants and Toddlers in New Mexico Hunger, Poverty, Health, and the Federal Nutrition Programs,” Food Research and Action Center, 2019

[8] Consumer Expenditures Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019

[9] “Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: The need for a trauma-informed social justice response,” Psychological Trauma, 12, 443-445, 2020

[10] One-Year Estimates, 2019, American Community Survey Demographics and Housing Estimates, US Census Bureau, 2020

[11] Ibid

[12] Food Insecurity Health Indicator Report, NM-IBIS, NM Department of Health, 2019

[13] “COVID-19 and Indigenous Peoples: An imperative for action,” Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29, 2737-2741, 2020

[14] “New Mexico food banks see surge in demand during pandemic,” KRQE TV, 2020

[15] Week 18 Household Pulse Survey: Oct. 28 – Nov. 9, US Census Bureau, 2020

[16] USDA Food Access Research Atlas, USDA, 2017

[17] “The Navajo Nation’s horrendous roads keep killing people and holding students hostage, but nothing changes,” Center for Health Journalism, 2019

[18] “One in Seven Adults in Immigrant Families Reported Avoiding Public Benefit Programs in 2018,” Urban Institute, 2019

[19] Essential but Excluded: How COVID-19 Relief has Bypassed Immigrant Communities in New Mexico, NM Voices for Children, 2020

[20] “Food Security Among Hispanic Adults in the United States,” USDA, 2011-2014, 2016

[21] Demographics and Housing Estimates, US Census Bureau, One-Year Estimates, 2019, American Community Survey, 2020

[22] “Better Information Could Help Eligible College Students Access Federal Food Assistance Benefits,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2018

[23] Basic Needs Security at UNM: 2020 Research Report, UNM Basic Needs Project, 2020

[24] #RealCollege During the Pandemic: New Evidence on Basic Needs Insecurity and Student Well-Being, Boise State University, 2020

[25] Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students, Young Invincibles, 2018

[26] “Association of Food Insecurity with Children’s Behavioral, Emotional, and Academic Outcomes: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 38, 135–150, 2017

[27] “Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children,” Pediatrics, 118, e859-68, 2006

[28] “Household food insecurity: associations with at-risk infant and toddler development,” Pediatrics, 121, 65-72, 2008

[29] “Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Obesity among Children and Adolescents: A Review of Systematic Literature Reviews,” Childhood Obesity, 11, 338-346, 2015

[30] “A cost constraint alone has adverse effects on food selection and nutrient density: an analysis of human diets by linear programming,” Journal of Nutrition, 132, 3764-3771, 2002

[31] “The association of child and household food insecurity with childhood overweight status,” Pediatrics, 118, e1406-13, 2006

[32] “The Intersection between Food Insecurity and Diabetes: A Review,” Current Nutrition Reports, 3, 324-332, 2014

[33] “Food Insecurity and Child Health,” Pediatrics, 144, 2019

[34] “Food Insecurity and Health Care Expenditures in the United States, 2011-2013,” Health Services Research, 53, 1600-1620, 2018

[35] “The lifetime costs of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review: Lifetime costs of childhood obesity,” Obesity Reviews, 19, 452-463, 2018

[36] “Fruit and Vegetable Consumption,” Health Indicator Report, NM Department of Health, 2018

[37] Ibid

[38] Improving Tax Credits for a Stronger and Healthier New Mexico, NM Voices for Children, 2019

[39] A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce the Number of Children in Poverty by Half in 10 Years, National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM), 2019

[40] “Missing Meals in New Mexico,” NM Association of Food Banks, 2010

[41] Interactive Map: SNAP Rose in States to Meet Needs but Participation Has Fallen as Economy Recovered,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), 2019

[42] “Food Stamp Program participation is associated with better academic learning among school children,” Journal of Nutrition, 136, 1077-1080, 2006

[43] “Protective Association between SNAP Participation and Educational Outcomes Among Children of Economically Strained Households,” Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition, 12, 181-192, 2017

[44] “The effect of food stamps on children’s health: Evidence from immigrants’ changing eligibility,” Journal of Human Resources, 0916-8197R2, 2018

[45] “Food assistance programs and child health,” The Future of Children, 25, 91-109, 2015

[46] SNAP is Linked with Improved Nutritional Outcomes and Lower Health Care Costs, CBPP, 2018

[47] Ibid

[48] “New Mexico Should NOT Tax Food,” NM Voices for Children, 2018

[49] More Adequate SNAP Benefits Would Help Millions of Participants Better Afford Food, CBPP, 2019

[50] “New Mexico Should NOT Tax Food,” NM Voices for Children, 2018

[51] “How the Federal COVID-19 Response Impacts New Mexico: Food Assistance,” NM Voices for Children, 2020

[52] The Roadrunner Roundup, Roadrunner Food Bank, 2019

[53] Reports from Roadrunner Food Bank and The Food Depot, 2020

[54] Percentage Students Eligible for Free or Reduced-Price Meals, NM Public Education Department, Custom data requests, 2019

[55] “How the Federal COVID-19 Response Impacts New Mexico: Food Assistance”

[56] NM Farmers’ Marketing Association, 2019

[57] “Association of Food Insecurity with Children’s Behavioral, Emotional, and Academic Outcomes: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 38, 135–150, 2017

[58] “Profile of Infants and Toddlers in New Mexico Hunger, Poverty, Health, and the Federal Nutrition Programs”

[59] A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, NASEM, 2019

[60] Improving Tax Credits for a Stronger and Healthier New Mexico

[61] A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty

[62] “2018 State Diaper Facts New Mexico,” National Diaper Bank Network, 2018

[63] “The US and the High Cost of Child Care,” ChildCare Aware of America, 2018