Improving Tax Credits for a Stronger and Healthier New Mexico

Improving Tax Credits for a Stronger and Healthier New Mexico

Download the full report with appendices (Feb. 2019; 20 pages; pdf)

Download tables showing WFTC amounts by legislative district (Feb. 2020; 3 pages; pdf)

By Amber Wallin, MPA, and Cirila Estela Vasquez Guzman, Ph.D.

Introduction

Our economy is strongest when people have money to spend. But when people who work full time still don’t earn enough money to cover the basics, our economy is not at its healthiest. Tax credits for low- and moderate-income working families are a common-sense way to spur economic activity and put money in the hands of consumers who will spend it. When we increase the income of hard-working New Mexicans through tax credits, we all win. Tax credits can improve well-being by increasing opportunities to thrive and enhancing physical and mental health. When families and children have better physical and mental health, we become a stronger state. Tax credits are also a cost-effective and non-stigmatizing way to help hard-working, low-income families get ahead.

In New Mexico, the Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC) is one of the most sensible parts of our tax code: it encourages work, helps to raise hard-working families out of poverty, and benefits 225,000 New Mexico children, while also pumping millions of dollars back into local communities. Currently worth 10 percent of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the WFTC is lower than the national average for such credits and should be raised to 15 or 20 percent. In addition, the state should: expand outreach efforts and low-cost tax preparation assistance; restrict the use of refund anticipation loans; support federal efforts to increase the EITC for childless workers; and consider disbursing the refund through periodic payments over the course of the year. Increasing the WFTC and making these other changes would be a smart investment in New Mexico’s businesses, and our working families’ income, health, and future.

The History of the Credits

The WFTC is the state’s equivalent of the federal EITC. Its eligibility levels and refund amounts are based directly on the EITC, and it increases, complements, and leverages the EITC’s ability to directly benefit New Mexico. The purpose of the EITC is to help offset more regressive taxes, reduce poverty, and incentivize employment for low-income workers. The EITC was first passed with bipartisan support under President Gerald Ford in 1975. In 1986, the EITC was indexed to rise with inflation under President Ronald Reagan who called the program “the best anti-poverty, the best pro-family, the best job-creation measure to come out of Congress.”1

Since its passage, the EITC has been strongly supported by both Republican and Democratic lawmakers on both the national and state levels. The District of Columbia and 29 states have enacted state-level credits modeled after the EITC in order to help offset regressive state taxes for low-income workers while also improving conditions for families and encouraging work among lower-income earners. (See Appendix A, for a list of states with EITC-based credits.)

New Mexico enacted the WFTC in 2007 at 8 percent of the EITC and raised it to 10 percent of the EITC in 2008. State-based EITCs, such as the WFTC in New Mexico, are critical to increasing the positive impacts of the federal EITC on children and families, particularly among families who face the biggest challenges. On average, state EITCs provide a 17.6 percent match of the federal EITC thereby enabling states to improve benefits for families and invest in the state’s economy.2

How the Credits Work

The EITC and the WFTC reduce poverty in two ways: through the short-term and more immediate impact of the credit itself and through the more long-term increases in family earnings, which can provide lasting benefits for children. These benefits are multi-generational because they stick with children as they enter adulthood, which in turn supports healthy social and physical development of their own children and the economic development of our state.

In 2018, the EITC reached nearly 26 million families nationwide. Research shows that in 2016, this tax credit lifted about 5.8 million families with approximately 3 million children out of poverty.4 Furthermore, the EITC reduced the severity of poverty for 18.7 million people, which benefited nearly 6.9 million children.

Who Claims the Credits

In the 2015 tax year, the most recent year for which data are available, nearly 210,000 New Mexico individuals and families (or 34 percent of the tax returns filed in the state) claimed the EITC and the WFTC. That year, New Mexico’s working families received more than $520 million from the EITC and more than $52 million from the WFTC. The average credit amount was about $2,700 when the two refunds are combined.5 Every legislative district and county in New Mexico benefits from the credits. (See Appendices B, C, and D for EITC and WFTC amounts and percent of claimants by county, state House and Senate districts.)

As a group, those who claim the EITC and WFTC pay a large share of their incomes in taxes. In fact, in addition to the federal payroll taxes they pay, New Mexico’s lowest-income households pay a larger share of their income in state and local taxes than the households in every other income group. Those making less than $17,000 a year pay more than 10 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes. Meanwhile, New Mexicans who make more than $370,000 pay 6 percent of their incomes in those same taxes12 (see Figure IV). The lowest-income New Mexican taxpayers, therefore, are paying nearly twice the portion of their incomes in state and local taxes than are the richest New Mexicans. This huge disparity exists even after the current value of the EITC and WFTC are taken into account.

Putting the Credits to Work for New Mexico

The Credits Benefit New Mexico Workers

New Mexico has the highest overall poverty rate (20 percent) and second highest child poverty rate (27 percent) in the nation,13 but our high poverty rates would be even worse without the EITC and WFTC. Without these credits, nearly 40,000 more New Mexico families – including 20,000 more children – would live in poverty.14

New Mexico’s high poverty rates extend to workers and their families. The state is ranked among the worst in the nation in terms of poverty among the employed, among people who work full-time year-round, and among people who have a bachelor’s degree or higher.15 We also have one of the highest percentages in the nation of workers in low-wage jobs, so it is not surprising that New Mexico has the highest percentage (16 percent) of families that are working but still living below the poverty line, and the highest percentage (43 percent) of working families that are low-income (below 200 percent of the federal poverty level). Because so many of our working families are low income or living in poverty, we also have the worst rankings in the nation of the percent of children in working families that are low-income or living in poverty.16

New Mexico also has one of the highest rates of income inequality in the nation – meaning there is a large gap between what the lowest-income New Mexicans earn and what the highest-income New Mexicans earn.17 Income inequality puts our economy out of balance in part because too much income is concentrated into too few hands where it is less likely to be spent. Growing income inequality is especially destructive in New Mexico because while the rest of the nation has already bounced back from the Great Recession, New Mexico’s recovery is only now beginning to pick up. Economic recoveries happen more quickly when increases in income and employment are broadly shared and spread across all income levels. However, in contrast with historical economic recoveries, income and employment recoveries of the last recession have taken longer to reach low- and middle-income earners, especially in New Mexico. As the gap between the wealthiest and the poorest gets bigger, gains – including recession recovery gains – go very disproportionately to the richest. Tax credits like the EITC and WFTC that target benefits to low-income workers give these hard-working families a hand-up while helping to limit the growing gap in income inequality.

The EITC and WFTC not only help increase workers’ incomes, but they also help low-income families continue to participate in the workforce because they help pay for necessities like child care, transportation, and education or job training programs. This is good for businesses because workers who can pay for these basic needs are more reliable employees. Families earning very low wages see larger refunds as their incomes rise, which encourages them to work more hours. Extensive research shows that the EITC has been successful at encouraging and increasing work, especially among single parents, and particularly among single mothers.18 Increased work and earnings among low-income families has the effect, in turn, of reducing dependence on public assistance and shrinking Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF, the program formerly known as welfare) caseloads. Workers who receive credits like the EITC and WFTC also boost their Social Security earnings and retirement benefits, which can help reduce the incidence or severity of poverty in old age.19 Research shows that the EITC increases employment and reduces the need for public assistance across generations.

The Credits Benefit New Mexico Children and Families

The WFTC is a relatively small investment on the part of the state that can make a big difference in the health and well-being of New Mexico’s children and their families. That influence can begin prenatally and extend into adulthood. (See the ‘Tax Credits Are Health Credits’ sidebar for information on the many health benefits associated with tax credits like the EITC and WFTC.)

In addition to significant health benefits, children in families that receive the EITC and WFTC also see improvements in educational outcomes. Mothers who receive the EITC read to their children more frequently and assist their children more frequently with homework.20 The younger the children are at receipt of these tax credits, the better the academic and economic outcomes are. Earlier access to EITC leads to better school performance among elementary and middle school students21, 22 but benefits are also seen if the tax credit is received later in adolescence.

In one study, an additional $1,000 in EITC in the spring of high school senior year was shown to increase college enrollment by roughly half for student populations receiving the credit.23 Receipt of the EITC also increases both high school and college graduation rates.24

Because higher incomes from refundable tax credits are associated with better health, more education, and higher skills, children in families receiving EITC and WFTC are more likely to work and earn more as adults.25 In fact, children from EITC families, on average, go on to earn 17 percent more when they reach adulthood then do children from low-income families who do not receive the EITC.26 Perhaps because of these impacts, studies show that progressive state income tax provisions – including EITC and WFTC – are linked to increased intergenerational income mobility.27 This relationship strengthens with the size of the state-based EITC, and in states with larger credits, low-income children are even more likely to move up the income ladder over time.28

The Credits Benefit New Mexico Businesses

The EITC and WFTC are also good for business because they are good for the state’s economy. Last year alone, New Mexico’s low-wage workers received more than $570 million from the EITC and WFTC combined – much of which was pumped right back into the economy through rent payments, purchases of groceries and other household necessities, and to pay for child care. Research shows that EITC households spend their credits quickly and locally, and that local economies benefit as a result. Economists categorize the economic impacts of injections of money into an economy (in this case, federal EITC money into New Mexico’s economy) as the sum of: direct impacts (EITC recipients spending their refunds); indirect impacts (businesses spending more in response to EITC spending at those businesses); and induced impacts (changes in spending patterns caused by direct and indirect impacts).

Together these economic impacts are referred to as the “multiplier” effect of a program.29 The EITCis widely known to have a very strong multiplier effect. In fact, it is estimated that for every $1.00 claimed from the EITC, $1.50 to $2.00 is generated in local economic activity.30 That means the EITC alone could be responsible for somewhere between $780 million and more than $1 billion in economic activity in New Mexico each year. This economic activity is important in metro areas, but may be especially crucial in rural areas of New Mexico. (See Appendix B for EITC amounts and percent of claimants by county.)

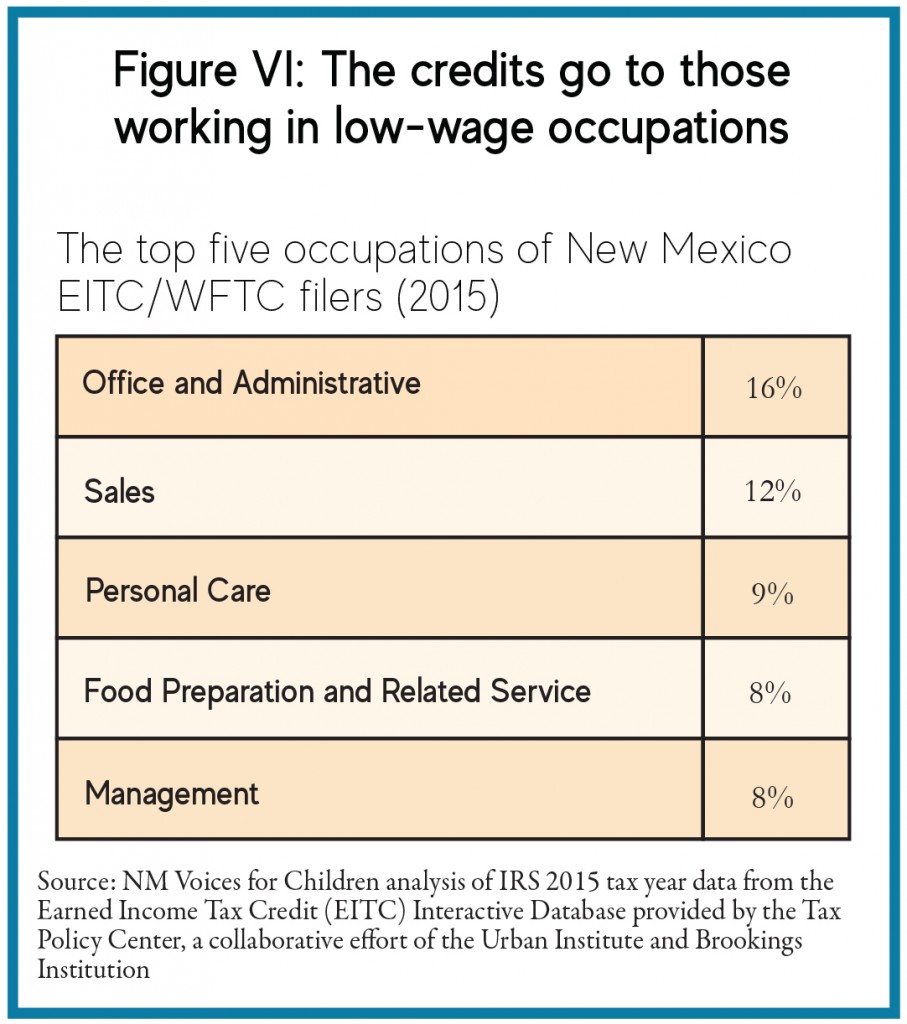

The EITC has other economic benefits as well. Though it is widely regarded as one of our nation’s most successful anti-poverty programs,31 the EITC was originally intended to primarily act as an economic stimulus.32 Over time, many governments have pushed for expanded EITC participation in their states for this very reason – to increase spending in their economies.33 The EITC and WFTC also benefit employers by enabling workers to better support their families even on meager wages. It has been estimated that as much as 36 cents of every dollar of an EITC credit directly benefits employers by lowering the cost of labor.34 This trend is likely to hold up in New Mexico, where we not only have one of the highest rates of working poor and working low-income families in the nation, but also one of the highest rates – 34 percent – of employment within occupations whose median annual pay is below the poverty threshold for a family of four.35

Tax Credits Are Health Credits

Social and economic conditions are critical determinants of both individual health and population health,36 but the health impacts of economic policies that shape the distribution of income and wealth are often overlooked. A growing body of literature shows that economic policies contribute both directly and indirectly to health. We know today that economic policies that directly target working-class families can improve population health more than policies that target the rich or the population overall.37 Policy levers that create opportunities and eliminate barriers in order to achieve health equity include the Medicaid expansion, laws to increase the minimum wage, state-funded pre-K, and housing assistance programs.Tax policies are also important health drivers. For example, increased tax revenues that leads to investments in infrastructure, such as mass transit, can improve the health and well-being of our communities. But in the current research connecting tax policy to health, the tax policy that looms largest and is most often linked to health is the EITC – and research suggests that the size of the credit impacts the extent of the improvement.

Research shows that the health benefits for children of the EITC begin in infancy.38, 39 A large body of research40 documents a positive relationship between increased EITC income and improved birth weights. On average, every $1,000 of EITC income is associated with a 7 percent decrease in the likelihood of babies being born at a low weight. Increases in the EITC have also been linked with increased likelihood for prenatal care, and decreased maternal smoking and drinking during pregnancy.41 The more generous these tax credits are, the more likely it is that smoking rates are reduced, maternal mental health is improved, and low-birthweight rates are decreased, among other improved health outcomes in families receiving the EITC.

The tax credit also is associated with increased private health insurance coverage for children ages 6 to 14.42 Lifting the income of families of limited means when a child is young not only tends to improve children’s immediate health insurance coverage and access to health services, but is also associated with an increased likelihood of additional training and/or schooling, which is also linked to improved health outcomes.

Receipt of EITC also improves the health of adults, with a 9 percent increase in self-reported health status as ‘very good or excellent43 and a 4 percent decrease in state age-adjusted mortality rates.44 There is also a reduction in mental stress, including maternal stress.45, 46 The EITC is also linked to improved health coverage rates in adults. It contributed to a 4 percent increase in coverage for health insurance among adults with low skills47 and a 5 percent increase in health insurance coverage among single mothers with a high school education or less.48

The EITC is successful at improving health because good health is more than health behaviors or clinical care. Socio-economic factors account for nearly half of a person’s health outcomes. For example, upon receipt of the EITC, families may finally be able to secure a vehicle and have transportation when they need it for regular doctor visits, or they may now be able to move to a neighborhood with less crime or better schools, which may lead to long-term health benefits.49 Being able to get to one’s job and make ends meet decreases stress, which also provides additional emotional resources to the family. Additionally, parents may now be able to afford tutoring or other activities that help increase their children’s educational achievement, which in turn leads

to improved long-term health benefits.

More and more, researchers are investigating and articulating the connections between tax policies – including tax credits – and health.50 If expanded, the WFTC has the potential to have a greater impact on the next generation of children, thereby breaking the cycle of poverty. This policy is one of the few that have resulted in documented positive effects at all stages of life.

The Credits Build Opportunities for People of Color and Women

Evidence suggests that the federal and state-level EITCs are particularly effective at reducing poverty among households of color and among women.51 This is important in New Mexico, where people of color and women are more likely to live in poverty than their White and male peers. Children of color – who make up the majority (75 percent) of the state’s child population – are even more likely to face troubling economic conditions. In New Mexico, 30 percent of Hispanic children and 42 percent of Native American children live in poverty compared to 13 percent of non-Hispanic White children.52 Consequently, children of color are more likely to see the greatest benefits from the EITC and WFTC because they are the most likely recipients of the credits. As noted previously in the report, 52 percent of EITC and WFTC recipients in New Mexico are Hispanic and nearly 16 percent are Native American.

The EITC and WFTC can reduce poverty in families of color by alleviating high housing costs, for example. A larger portion of the income of families of color goes to housing costs, which limits the family’s ability to cover other necessities such as food, health care, and transportation. Nationally in 2016, 45 percent of African American and 43 percent of Hispanic children – compared to 23 percent of White children – lived in households with a high housing cost burden. New Mexico is ranked 35th in affordable housing as compared to the rest of the states.53 Increases in income through the EITC and WFTC can help families of color in our state address housing costs.

The EITC and WFTC also address racial and ethnic inequity by assisting children who are more likely to be at an educational and health disadvantage compared to their higher-income peers54 and increase opportunities for a better future among low-income families and children of color who often face much greater economic and health challenges. Credits like the EITC and WFTC are some of the best options to close those economic and health gaps.

These tax credits also provide benefits for single women who experience big gains in their physical and mental health because of the additional income. Single women are more likely to get health insurance as a result of the EITC55 and mothers who receive the EITC have improved prenatal health and birth-weight outcomes.56 Research also shows that a more generous EITC targeted to unmarried women with preschool-aged children leads to larger gains in earnings and wages in the long run.57 Since the introduction of the EITC program in 1975, there has been a 6 percent increase in mothers who are working, despite little change in child care subsidies or maternity leave policies – with employment increases highest among single mothers.58

We have significant incentives to improve programs like the EITC and the WFTC that help working mothers thrive. Of low-income working families, 41 percent are headed by working mothers. This is important because working mothers who are low-income are often employed in retail and service-sector jobs that pay low wages, limit work hours, and fail to provide benefits, such as health insurance and paid sick leave, which are crucial to the health and success of families and children.59

Preparing for America’s future requires us to ensure that we support all contributing members of our communities – no matter where they live, their gender, their racial and ethnic backgrounds, or how much their parents earn.

The Truth about Overpayments and Errors

1. The overpayment rate is overstated and based on older data.

- More than 40 percent of claims counted as “overpayments” were determined to be valid on further review.60

- The overpayment rate does not fully account for corresponding underpayments. For example, if a father mistakenly claims an EITC for a child that lives with the mother, the full amount is counted as an overpayment but the amount unclaimed by the eligible mother is not taken into account. Overpayment estimates are based on 2009 data, and do not reflect the significant additional enforcement measures the IRS has implemented since then.

2. Most EITC overpayments are due to honest mistakes, not intentional fraud.

- IRS studies acknowledge the majority of errors are unintentional61 and stem from the combination of

the complexity of the EITC’s rules and the complexity of many family living arrangements.62 - Most EITC errors occur on commercially prepared returns,63 and commercial tax preparers, not

individual filers, are responsible for 75 percent of the value of EITC overpayments.64

3. EITC errors cost significantly less than business tax noncompliance.

- A 2012 IRS study found that 56 percent of business income went unreported in 2006. This cost $122 billion in uncollected revenue – more than ten times the size of estimated EITC overpayments that year.65

- The EITC rate of noncompliance is substantially lower than the rate in a number of other parts of the tax code, and accounts for a very small share (less than 3 percent) of the estimated $450 billion tax compliance gap.

IRS Actions to Reduce EITC Overpayments66

- More than 80 percent of EITC claims are now filed electronically, better enabling the IRS to identify questionable EITC claims before paying them.

- A powerful IRS database identifies questionable EITC claims, targeting nearly 500,000 claims annually for examination.

- The IRS is implementing rules to require preparers to register and pass a competency exam that promises to be a major step forward.

- In 2013, the IRS identified 7,000 preparers with high error rates in the EITC claims they filed. It carried out a range of interventions with these preparers before and during the 2013 filing season, including educational visits by IRS agents. Overall, this strateg y alone averted an estimated $590 million in erroneous claims, according to the IRS.

Policy Recommendations

Evidence that New Mexico’s Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC) helps working families and spurs the economy is abundant. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) also enhances the health and well-being of families and children in our state. However, the credit could do even more and have a bigger positive impact in our state with some improvements.

- Increase the value of the WFTC: At 10 percent, New Mexico’s WFTC is below the national average among states that have a similar EITC-based tax credit (see Appendix A). Lawmakers should increase the credit from 10 percent to at least 15 percent of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit. Raising the credit to 15 percent of the EITC would mean investing $26 million more in our economy and our hard-working, low-income families. This practical investment will make a big difference for New Mexico families struggling to get by on low wages.

- Expand outreach efforts and tax preparation assistance: One in five eligible workers in New Mexico misses out on the EITC and WFTC, either because they don’t claim it when filing, or they don’t file a return. Tax assistance programs – such as the United Way and CNM’s Tax Help New Mexico program – that provide free (and bilingual) tax preparation for low-income New Mexicans are great models for tax preparation outreach. Lawmakers should expand outreach efforts like these and support free or low-cost tax preparation assistance in order to maximize the benefit of the credit. Expanding access to volunteer tax preparation services and free online tax filing would preserve more of the credits’ value for those filers that might otherwise face significant tax preparation fees or be pressured to buy costly refund products that eat up a large part of the credits, blunting their otherwise positive impacts. Additionally, due to the proven economic benefits of the EITC, expanding participation among eligible filers would increase transfer payments and benefit New Mexico’s economy.

- Restrict refund anticipation loans and checks: Another good reason for increasing access to free or low-cost tax preparation for low-income New Mexicans is that it keeps them from being preyed upon by commercial preparers offering refund anticipation loans (RALs) and refund anticipation checks (RACs). Thirty eight percent of New Mexico EITC and WFTC claimants receive RALs or RACs,67 and low-income taxpayers who claim the EITC represent the majority of the consumers for both products.68 RALs are very short-term loans made to the tax filer so they can receive a refund the same day, but they often come with significant fees and high interest rates. RACs are essentially the same thing except that a taxpayer must open a temporary bank account. Fees for preparation of the return and the RAC account are then deducted from the taxpayer’s refund before a check is issued. Tax preparers who push RALs and RACs often fail to tell their customers that they could receive their refund by electronic transfer in as little as two weeks at no cost. While IRS rules have led to a dramatic decrease in RALs among EITC claimants from 2007 to 2010, during the same time period, the percent of EITC recipients requesting RACs more than doubled, from 26 percent to 56 percent.69

- Both RALs and RACs disproportionately harm EITC and WFTC tax filers and can siphon off much of the value of the credits that is intended to help low-wage workers. New Mexico should limit the rate that can be charged on these refund options, mandate and standardize disclosure and marketing practices, and strictly enforce compliance among lenders.

- Support federal efforts to increase the EITC for childless workers: Working, childless adults are the only group effectively taxed into poverty or deeper into poverty by federal income taxes.70 These workers pay significant federal income and payroll taxes, yet receive little to no EITC, the credit that otherwise offsets significant portions of these taxes for low-income workers. In tax year 2013, the average combined credit for recipients in New Mexico with qualifying children was $3,334, while the average combined credit for New Mexico recipients without children was only $301. About 22 percent of EITC and WFTC returns in New Mexico are filed by childless workers, but less than 4 percent of the total EITC credit amount goes to these workers.71 Increasing the EITC for childless workers would not only raise their incomes and help offset taxes that send them into poverty, but, according to recent research, it could also help address low labor-force participation and high incarceration rates of childless, low-income workers.72

- Consider periodic payment options of the EITC and WFTC: The single annual disbursement of the EITC and WFTC can present challenges for workers struggling to support their families throughout the year. Research shows that about 95 percent of EITC recipients carry debt of some kind, and that in many families, significant portions of refunds may be spent on debt payments.73 Paying out a portion of filers’ refunds throughout the year would better enable them to cover daily and monthly expenses without taking on additional debt and then using the refund to pay off that debt (with added interest).74 This would also increase the chances that refunds are spent on goods and services at local businesses, rather than on high-cost financial products (like payday loans), many of which are serviced by large, multi-state financial institutions. A pilot program in Chicago that issued EITC recipients their refunds on a quarterly – rather than an annual – basis found that periodic payments improved overall financial stability for and reduced financial stress of EITC families. Pilot project researchers also reported that 83 percent of families in the program preferred quarterly payments to the standard annual method.75

Endnotes

- Quoted by Lea Donosky in “Sweeping Tax Overhaul Now The Law,” Chicago Tribune, October 23, 1986.

- Gagnon, D., Mattingly, M., and Schaefer, A. 2017. State EITC Programs Provide Important Relief to Families in Need. Carsey Research National Issue Brief #115.

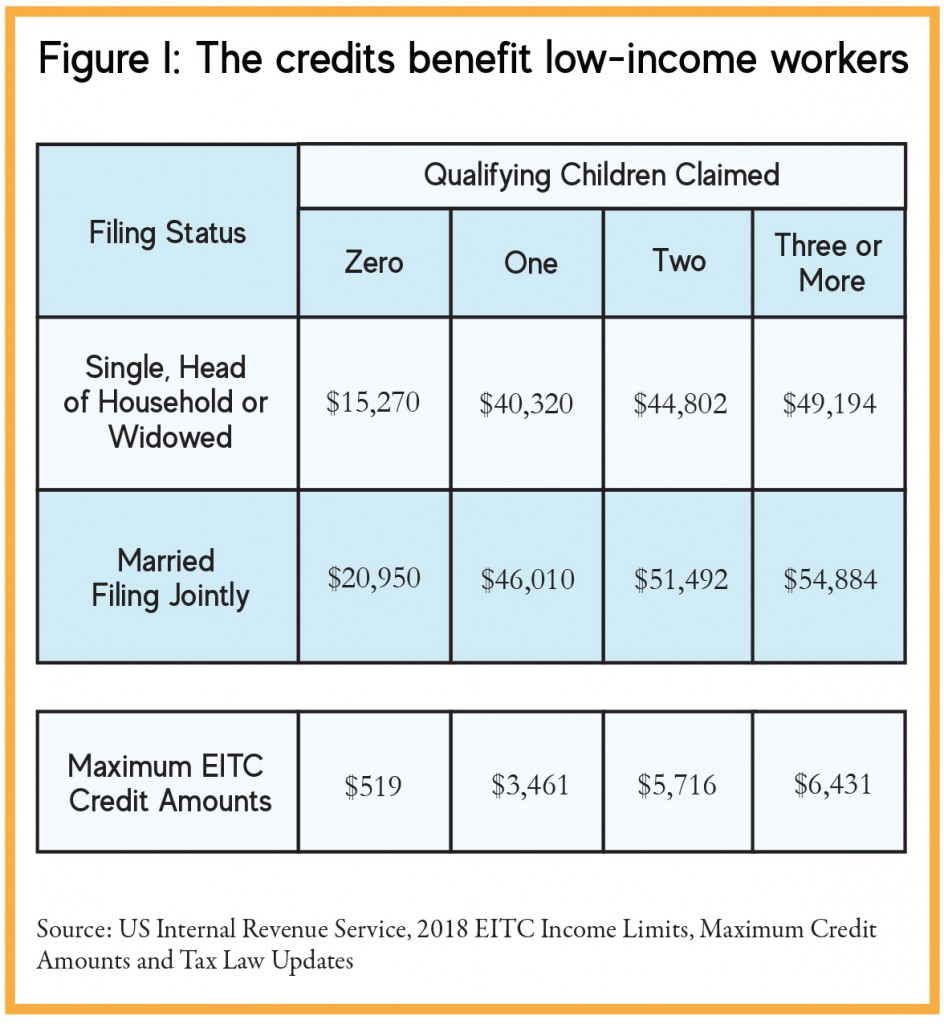

- EITC qualifications include: having earned income from things like wages, salaries, disability pay, and profits from owning your own business; being a U.S. citizen or resident alien for the entire tax year; having a valid Social Security number for everyone on the tax return; and not having income investments over $3,500.

- The Earned Income Tax Credit. April 2018. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) Policy Basics.

- NM Voices for Children analysis of IRS 2015 tax year data from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) Interactive Database provided by the Tax Policy Center, a collaborative effort of the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution.

- Ibid.

- Dowd, T., and Horowitz, J. 2011. “Income Mobility and the Earned Income Tax Credit: Short-Term Safety Net or Long-Term Income Support,” Public Finance Review.

- CBPP analysis of 2009-2012 American Community Survey data.

- KIDS COUNT Data Book. 2018. Annie E. Casey Foundation.

- Two Generation Approaches to Poverty Reduction and the EITC. 2015. Grantmakers Income Security Taskforce.

- The Earned Income Tax Credit. April 2018. CBPP Policy Basics.

- Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States. October 2018. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey data, 2017.

- Brookings Institution analysis of 2011 tax year data.

- US Census Bureau, American Community Survey data, 2017.

- Conditions of Low-Income Working Families in the States. Working Poor Families Project (WPFP), Population Reference Bureau analysis of U.S. Census American Community Survey data, 2016.

- On the Gini Coefficient measure, NM is 40th; on shares of income by quintile, NM is 44th. US Census, American Community Survey, 2014 data (1st being the best ranking a state can have, 50th being the worst ranking ).

- Eissa, N., and Hoynes, H. 2006. Behavioral Responses to Taxes: Lessons from the EITC and Labor Supply. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

- Two Generation Approaches to Poverty Reduction and the EITC. 2015. Grantmakers Income Security Taskforce.

- Averett, S., and Wang, Y. July 2015. The Effects of the Earned Income Tax Credits on Children’s Health, Quality of Home Environment, and Non-Cognitive Skills. IZA Discussion Paper Series No 9171.

- Duncan, G., Morris, P., and Rodrigues, C. 2011. “Does Money Really Matter? Estimating Impacts of Family Income on Young Children’s Achievement with Data from Random Assignment Experiments.” Developmental Psychology 1263-1279.

- Dahl, G., and Lochner, L. 2012. “The impact of family income on child achievement: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit.” The American Economic Review 102(5): 1927-1956.

- Manoli, D., and Nicholas, T. January 2014. Cash On Hand and College Enrollment: Evidence from Population Tax Data and Policy Nonlinearities. NBER. Working Paper 19836.

- Thomas, P.W. November 2017. Childhood Family Income and Adult Outcomes; Evidence from the EITC. Purdue University.

- EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds, CBPP, revised in 2015.

- Duncan, G., Ziol-Guest, K., and Kalil, A. 2010. “Early-Childhood Poverty and Adult Attainment, Behavior, and Health,” Child Development, January/February 306-325.

- Two Generation Approaches to Poverty Reduction and the EITC. 2015. Grantmakers Income Security Taskforce.

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Kline, P., and Saez, E. 2015. The Economic Impacts of Tax Expenditures: Evidence from Spatial Variation Across the U.S., special report for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

- Holmes, N., and Berube, A. 2015. The Earned Income Tax Credit and Community Economic Stability. Brookings Institution.

- Avalos, A., and Alley, S. 2010. “The economic impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in California.” California Journal of Politics and Policy.

- Dollar Wise: The Best Practices on the Earned Income Tax Credit, U.S. Conference of Mayors, 2008.

- Ben-Shalom, Y., Moffitt, R., and Scholz, J. 2011. An Assessment of the Effectiveness of Anti-Poverty Programs in the United States, NBER; and The Earned Income Tax Credit at Age 30: What We Know. 2016. Brookings Institution.

- Nichols, A., and Rothstein, J. 2015. The Earned Income Tax Credit, NBER.

- Berube, A. 2006. Using the Earned Income Tax Credit to Stimulate Local Economies. Brookings Institution.

- New Mexico ranks 42nd in the nation on this measure. WPFP analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics May 2015 Occupational Employment Statistics.

- Kaplan, G.A., and Lynch, J.W. 1997. “Editorial: Whither studies on the socioeconomic foundations of population health?” American Journal of Public Health 87(9): 1409-1411.

- Rigby, E., and Hatch, M.E. 2016. “Incorporating Economic Policy into a ‘Health-In-All-Policies’ Agenda,” Health Affairs 35(11): 2044-2052.

- Hoynes, H.W., Miller, D.L., and Simon, D. 2015. “Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7(1): 172-211.

- Baker, K. University of Notre Dame mimeo, 2008; and Strully, K.W., Rehkopf, D.H., and Xuan, Z. “Effects of Prenatal Poverty on Infant Health: State Earned Income Tax Credits and Birth Weight.” American Sociological Review (August 2010), 1-29.

- Haman, R., and Rehkopf, D.H. 2015. “Poverty, Pregnancy, and Birth Outcomes: A Study of the Earned Income Tax Credit.” Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol Sep. 29(5):444-452.

- Hoynes, H.W., Miller, D.L., and Simon, D. 2012. Income, The Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health, NBER; and Baker, K. Do Cash Transfer Programs Improve Infant Health: Evidence from the 1993 Expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit. University of Notre Dame.

- Baughman, R.A., and Duchovny, N. 2016. “State Earned Income Tax Credits and the Production of Child Health: Insurance Coverage, Utilization, and Health Status.” National Tax Journal 69(1): 103-132.

- Lenhart O. 2018. The effect of income on health: New evidence from Earn Income Tax Credit. Review of Economics of the Household 1-34.

- Muennig, P.A., Mohit, B., Wu, J., Jia, H., Rosen, Z. 2016. “Cost effectiveness of the earned income tax credit as a health policy investment.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 51(6):874-881.

- Evans, W.N., and Garthwaite, C.L. 2014. “Giving Mom A Break: The Impact of Higher EITC payments on Maternal Health.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 6(2): 258-290.

- Boyd-Swan, C., Herbst, C., Ifcher, J., and Zarghamee, H. 2013. The earned income tax credit, health, and happiness. IZA Discussion Paper 7261.

- Baughman, R.A. 2005. “Evaluating the Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Health Insurance Coverage.” National Tax Journal, 58(4): 665-84.

- Cebi, M., and Woodbusy, S.A. 2014. “Health insurance tax credits, the earned income tax credit, and health insurance coverage of single mothers.” Health Economics 23(5):501-503.

- Smeeding, T., et al. 1999. The Earned Income Tax Credit: Expectation, Knowledge, Use, and Economic and Social Mobility. Center for Policy Research: Paper 147.

- Simon, D., McInerney, M., and Goodell, S. Oct. 2018. “The Earned Income Tax Credit, Poverty, and Health.” Health Affairs Health Policy

Brief: Culture of Health. - State Earned Income Tax Credits Help Build Opportunity for People of Color and Women. CBPP. July 2018.

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2017 American Community Survey Data accessed through the KIDS COUNT Data Center.

- Talk Poverty data by state, New Mexico, 2018 https://talkpoverty.org/state-year-report/new-mexico-2018-report/.

- Silvis, J. Feb 2016. Six Ways the EITC Helps Kids in Schools. Get it Back Blog. http://www.eitcoutreach.org/blog/six-ways-the-eitc-helps-kids-in-schools/.

- Cebi, M., and Woodbusy, S.A. 2014. “Health insurance tax credits, the earned income tax credit, and health insurance coverage of single mothers.” Health Economics. 23(5):501-503.

- Haman, R., and Rehkopf, D.H. 2015. “Poverty, Pregnancy, and Birth Outcomes: A Study of the Earned Income Tax Credit.” Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol Sep. 29(5):444-452.

- Neumark, D., and Shirley, P. 2017. The Long-Run Effects of the Earn Income Tax Credit on Women’s Earnings. NBER. Working Paper No. 24114. (Issued Dec 2017 and revised May 2018).

- Bastin, J. April 2016. The Rise of Working Mothers and the 1975 Earned Income Tax Credit. Thesis, University of Michigan.

- Povich, D., Roberts, B., and Mather, M. 2014. Low-Income Working Mothers and State Policy: Investing for a Better Economic Future, WPFP.

- Testimony of Nina Olson, IRS National Taxpayer Advocate, before U.S. House Appropriations Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government, February 26, 2014, p. 32.

- Holtzblatt, J., and McCubbin, J. “Issues Affecting Low-Income Filers” in The Crisis in Tax Administration, by Aaron, H., and Slemrod, J., Brookings Institution Press, November 2002; and Liebman, J. November 1995. “Noncompliance and the EITC: Taxpayer Error or Taxpayer Fraud.” Harvard University.

- Department of the Treasury, Agency Financial Report (AFR), fiscal year 2013, p. 207. It is estimated 70 percent of issues relate to complex residency and relationship requirements and confusion on claiming eligible children. The remaining 30 percent of EITC improper payments stem from verification of wage and self-employment income. (EITC recipients are as likely to be self-employed as other taxpayers.) Income verification issues regarding self-employment are a concern in the tax code as a whole, not unique to the EITC.

- Testimony of John A. Koskinen, IRS Commissioner, before US House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Oversight, February 5, 2014.

- Based on IRS audits of EITC claims in the IRS study, “Compliance Estimates for the Earned Income Tax Credit Claimed on 2006-2008 Returns,” as reported in Estimated Earned Income Tax Credit Annual Overclaims, by the CBPP.

- Tax Gap for Tax Year 2006: Overview. IRS. January 6, 2012. ese figures, which are for 2006 tax returns, represent the estimated impact of business under-reporting in the personal income tax; they do not include under-reporting or other sources of error in the corporate income tax.

- Greenstein, R., Wancheck, J., and Marr, C. April 2014. Reducing Overpayments in the Earned Income Tax Credit. CBPP.

- NM Voices for Children analysis of 2015 IRS income tax data provided by the Brookings Institution.

- EITC Interactive: User Guide and Data Dictionary. Brookings Institution, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Marr, C., Huang, C.C., Murray, C., and Sherman, S. 2016. Strengthening the EITC for Childless Workers Would Promote Work and Reduce Poverty. CBPP.

- NM Voices for Children analysis of 2013 IRS tax data provided by Brookings Institution.

- Marr, C., Huang, C.C., Murray, C., and Sherman, S. 2016. Strengthening the EITC for Childless Workers Would Promote Work and Reduce Poverty. CBPP.

- Holmes, N., and Berube, A. 2015. The Earned Income Tax Credit and Community Economic Stability. Brookings Institution.

- Holt, S. 2015. Periodic Payment of the Earned Income Tax Credit Revisited. Brookings Institution.

- Bellisle, D., and Marzahl, D. 2015. Restructuring the EITC: A Credit for the Modern Worker. Center for Economic Progress.

Download the full report with appendices (Feb. 2019; 20 pages; pdf)