Full Inclusion of Our Immigrant Population Would Lead to a More Prosperous New Mexico

Download this report (Feb. 2021; 20 pages; pdf)

Introduction

New Mexico is strongest and our future is brightest when everyone is able to make their unique contributions to our communities and the state. We all lose out when someone is hindered from contributing because of where they were born or how they arrived here. But that is the fate for too many New Mexicans who have come here wanting nothing more than to work hard and seek a better life.

At no time has this been so clear as during the COVID-19 pandemic, when federal relief enacted in 2020 was denied to many families with immigrant members. In New Mexico, more than $55 million in assistance was held back from more than 30,000 adults and 38,000 children. This loss of federal funding harms more than the families themselves. Relief funding during a recession is critical for supporting the small businesses where that money is spent, helping state and local economies.

Immigrants bring many assets to New Mexico including cultural and economic vibrancy, and entrepreneurship, and they expand the workforce needed by some of the state’s most critical industries. Regardless of their documentation status, immigrants are making vital contributions. New Mexico immigrants are business owners, construction workers, caretakers, students, and investors.

The contributions of immigrants have been particularly important during the Coronavirus pandemic. While COVID-19 has disrupted our lives and economy, immigrants across our nation are among those at the frontlines every single day, putting their lives at risk to ensure that grocery stores have fruits and vegetables, that restaurants can make and deliver food, that roads and highways are constructed and repaired, and that hospitals remain clean.

This report examines the multiple ways in which our state and nation are stronger because of our diverse and hardworking immigrant population – including their contributions to the state’s economy and tax system – and provides policies our lawmakers can enact so immigrant New Mexicans continue to strengthen our state.

Immigrants are an inextricable part of our state’s and our nation’s histories and culture. New Mexico can strengthen all families and communities through progressive and equitable immigrant-friendly policies that give all residents the opportunities needed to thrive. Treating our immigrant neighbors, workers, and colleagues equitably is essential to creating a strong economy and a brighter future for our nation and our state. We all win when we can all fully participate in our society.

Immigration Overview

The United States has long been perceived as a land of opportunity, a place where prospective citizens can achieve prosperity and upward mobility. Despite this, many Americans voice concerns about the overall impact immigrants have on this country. These fears, misconceptions, and anti-immigrant perspectives are echoed throughout public discourse. However, a continuously growing body of research consistently reports that immigrants have a net positive impact on the American economy, society, and culture.[1] Exacerbated by a former president who embraced xenophobic and anti-immigrant rhetoric and federal policies, the disconnect between perception and reality on immigration is particularly stark, but it’s hardly unprecedented.

Immigrants in our nation have been scapegoated, exploited for cheap labor, and treated as second-class citizens for hundreds of years.[2] This country’s xenophobic and exploitive history of immigration has shaped contemporary race relations.[3] Our immigration system is overly complex and broken, but Congress has failed to enact comprehensive immigration reform despite numerous attempts over the last three decades.[4] Aspiring citizens who are people of color continue to face the most difficult path to acceptance and eventual integration, as they have for much of the country’s history.[5] In fact, restrictive policies and discrimination have been part of the history of immigration in the United States and include the Chinese exclusion acts of 1875 and 1882 and the Texas Proviso of 1952. Historical racism and contemporary patterns of racial and ethnic bias and discrimination impact immigrants’ income, consumption patterns, property values, ability to build financial assets, and access to other vital resources.[6] The U.S. continues to welcome immigrants’ labor, but not immigrants themselves.

In addition to his inflammatory, xenophobic rhetoric, former President Trump instituted numerous policies that largely echo this country’s historically racist immigration laws. The rhetoric and policies focusing on deportation, family separation, and border militarization, have created a climate of fear for immigrants. Moreover, this type of fear tends to spread to the broader community, inhibiting group cohesion and limiting the community’s ability to thrive. Given their trepidation, uncertainty, and the hate directed specifically at immigrants, their possibilities for societal inclusion and meaningful community participation are constricted. Meanwhile psychological distress and poor health outcomes among immigrant individuals, families, and communities have increased.[7] When we prohibit immigrants’ full participation in our society, we harm the future of our nation.

A Timeline of Selected Race-Related U.S. Immigration Policies

New Country

- Naturalization Act of 1790: establishes citizenship of immigrants by naturalization and restricts it to free, land-owning, white males.

- Naturalization Act of 1795: repeals the Act of 1790 and extends by 3 years the residency requirement, which is extended by another 9 years in 1798.

Post Civil War

- Page Act of 1875: first restrictive immigration law, effectively barring entry of Chinese women.

- 1878: In the In re Ah Yup case, U.S. Supreme Court rules individuals of Asian descent ineligible for citizenship.

- Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882: prohibits immigration of Chinese laborers; is renewed in 1892, made permanent in 1903, and finally repealed in 1943.

- Immigration Act of 1917: imposes a literacy requirement making it the first act to restrict immigration from Europe; establishes an Asiatic Barred Zone, which bars immigration from the Asia-Pacific area.

- Immigration Act of 1924: imposes quotas (based on the National Origins Formula) on immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere and extends the Asiatic Barred Zone to Japan.

- 1942: President Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, leading to the internment of 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, the majority of whom were U.S. citizens.

Post WWII

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952: abolishes racial restrictions found in statutes going back to 1790; retains a quota system for nationalities and regions; allows for the admission of refugees on a parole basis.

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: eliminates national origin, race, and ancestry as basis for immigration while maintaining per-country limits; establishes a seven-category preference system.

End of 20th Century

- Refugee Act of 1980: creates the Federal Refugee Settlement Program.

- Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986: criminalizes the employment of undocumented workers; establishes one-year amnesty for undocumented workers living in the U.S. since 1982.

- Immigration Act of 1990: provides family-based immigration visa, creates five employment-based visas, and creates a lottery diversity visa program to admit immigrants from countries whose citizenry are underrepresented in the U.S.

- Illegal Immigration Reform & Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996: expands which crimes make an immigrant eligible for deportation; makes it more difficult for unauthorized immigrants to gain legal status.

Post September 11

- Patriot Act of 2001: gives the federal government the power to detain suspected “terrorists” for an unlimited time period without access to legal representation.

- 2012: Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA): executive order by President Obama provides a work authorization permit to those who arrived in the U.S. when they were younger than 16 and before the year 2012, have remained in this country since then, have no criminal history, and are enrolled in school or have graduated.

- 2017: Attempts to rescind DACA: President Trump attempts to terminate DACA via an executive order; however, the initiative has thus far been thwarted by numerous challenges in federal court, including the Supreme Court decision, Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California.

- 2020: Public Charge Rule Change: executive order restricts poorer immigrants, specifically those who use federal assistance programs like Medicaid or SNAP, from obtaining permanent residency status; it was still working its way through the court system at the time this report was released.

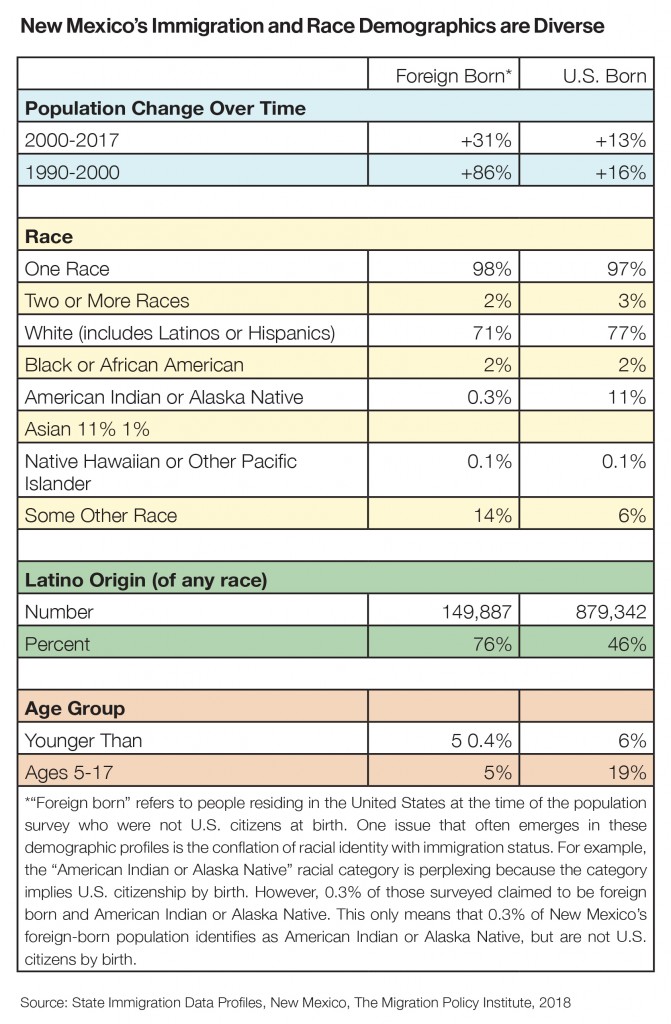

New Mexico’s Immigrant Population

New Mexico has a population of a little more than 2 million (2,095,428),[8] made up of both native- and foreign-born people, citizens and immigrants. Foreign-born New Mexicans can be naturalized U.S. citizens, resident aliens, immigrants with a temporary status such as a visa, or undocumented. Nearly 200,000 New Mexicans, or about 10% of our state’s population, are foreign-born.[9] Between 1990 and 2000, New Mexico experienced an 86% increase in the foreign-born population, and between 2000 and 2017, it experienced a 30% increase.[10] This uptick in immigration was primarily driven by a booming economy in the U.S., which attracted immigrants from Latin American, in particular Mexico, where the economy was stagnating.[11] Currently it is estimated there are some 60,000 undocumented immigrant residents in New Mexico.[12] They are equivalent to less than one-third of the non-citizen immigrant population in the state.

Of those New Mexicans who are foreign-born, the vast majority (75%) are from Latin America (South America, Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean). Of that group, just under two-thirds (68%) are from Mexico. Consistent with national trends, the most recent wave of Latino immigrants (those arriving after 2010) to New Mexico come from Central America and are mostly driven here because of conflict and violence in their home countries.[13]

New Mexico’s mix of families is diverse, multiracial, and multilingual. Whether U.S.- or foreign-born, a large share of New Mexicans speak languages other than English. About 30% of state residents speak Spanish at home and almost 10% speak Navajo.[14] Many families in New Mexico are of mixed immigration status, meaning some members are immigrants and some are not. Very few children younger than 5 in New Mexico are foreign-born themselves, in fact only 0.4% as of 2018. However, 20% of all New Mexico children (ages 5 to 17) live with at least one foreign-born parent, and 38,000 children have parents who are undocumented, including 8% of New Mexico’s K-12 students. Foreign-born and U.S.-born New Mexicans share interwoven lives, and their collective futures are inextricably linked: we share schools, communities, places of worship, and workplaces.

Immigrants Contribute Economically and Pay Taxes

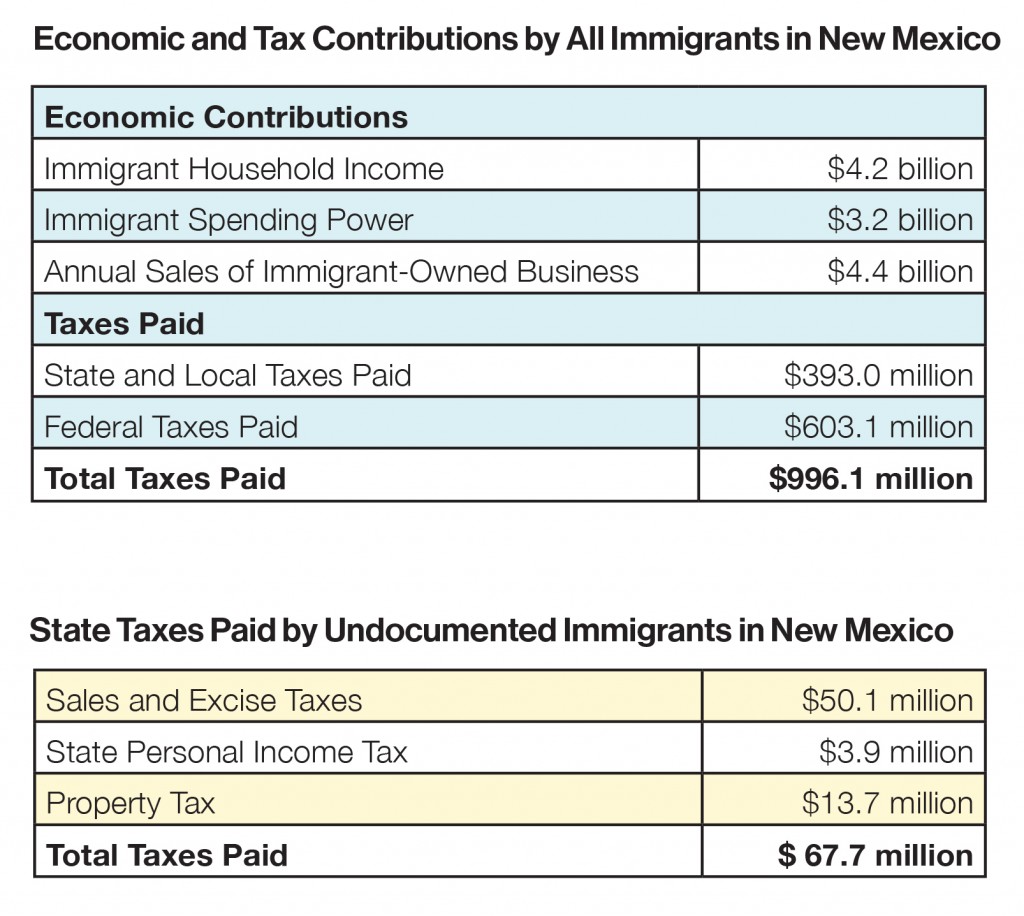

Immigrants have a substantially positive fiscal impact on the national economy, spending as much as $3.2 billion on goods and services, in addition to housing. Thus, they hold a tremendous amount of purchasing power.[15] Much of that purchasing requires the payment of taxes. Every time an immigrant purchases goods, fills their car with gas, and pays their cable bill, they are paying federal, state, and local taxes. Moreover, immigrants also pay property taxes as homeowners and as renters – because landlords typically pass their property tax expense on to renters. In New Mexico, 45% of undocumented immigrants are homeowners and those who do not own homes pay nearly $232.4 million in rent.[16]

The hundreds of billions of dollars in taxes paid by immigrants help sustain valuable government services and programs such as Social Security, unemployment insurance, and free and reduced-priced school lunches. New Mexico’s immigrant population pays a total of $996.1 million in federal, state, and local taxes.[17] The state and local share of those taxes, $393 million, stays here in New Mexico, supporting our public schools, hospitals, roads, and more.

Working immigrants, including those who are undocumented, also pay federal and state income taxes. Undocumented workers file their income taxes using an individual taxpayer identification number (ITIN) provided by the IRS. One report found that the 11 million undocumented immigrants living and working in the U.S. contribute more than $11.74 billion in state and local taxes every year.[18] An estimated 60,000 undocumented New Mexico residents pay more than $67.7 million annually in just state and local taxes including personal income taxes (nearly $4 million), property taxes (nearly $14 million), and sales and excise taxes (just over $50 million).[19] These revenue streams are the three principal ways the state and local governments fund public services, and for perspective, $67.7 million is enough to hire 1,860 teachers, 1,320 police officers or 1,115 public defenders.[20]

Like all residents in the U.S., immigrants make use of public services like education, health care, and public safety. However, immigrants’ economic contributions far outweigh the costs of any public services they incur. In other words, they contribute more money to federal, state, and local government budgets through taxes than they consume in the services paid for by taxes.[21] Immigrants are much less likely to make use of so-called safety net programs – they do not qualify for most anyway – and undocumented immigrants are ineligible for any safety net programs.

Dreamers Contribute to State and Local Revenues

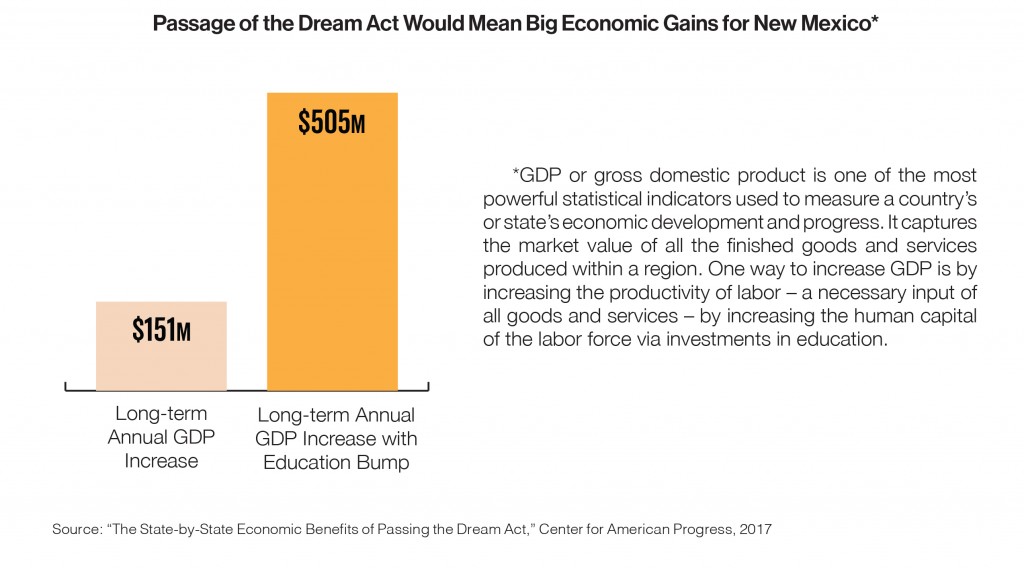

So-called Dreamers – those who applied and qualified for the DACA program (see the timeline of immigration policies to see qualification requirements for this program) – make unique and important contributions to New Mexico’s economy and pay state and local taxes. As of September 2019, there were about 6,000 Dreamers living, working, and paying taxes in our state.[22] It is estimated that New Mexico would lose as much as $16 million annually in state and local taxes if DACA recipients were to be deported. If DACA recipients are given a pathway to citizenship (i.e. if Congress passed the Dream Act), which would stabilize their contributions in the labor force, New Mexico’s annual GDP could increase by $151 million in the long-term. With additional investments in education, such as allowing access to more financial assistance for Dreamers wanting to complete a post-secondary education, the state GDP could gain as much as $505 million.[23]

Immigrants Create Jobs and Strengthen Our Workforce

Immigrants create jobs, strengthen our workforce, and they tend to be more entrepreneurial than non-immigrants, given that they are two times more likely than U.S.-born individuals to start a company.[24] For example, 40% of Fortune 500 companies were founded by immigrants or the children of immigrants.[25] As of 2018, there were 15,433 immigrant entrepreneurs in New Mexico, employing 27,014 New Mexicans in their businesses.[26] The total annual sales of immigrant-owned business in New Mexico is $4.4 billion.

The immigrant population has helped to sustain America’s shifting labor force. The role of immigrants in the workforce is particularly important as family sizes shrink and the baby boom generation ages, which reduces the share of the U.S.-born population that is of working age. Foreign-born residents are – and will continue to be – a vital part of the labor force of the nation and New Mexico. By 2024, 20% of New Mexico’s population will be over the age of 65, compared to 17.5% in 2020.[27] That is equal to a 14% growth in the share of the population older than 65. Younger immigrants are therefore filling crucial gaps in the market. Without more migration into New Mexico of working-age population, today’s children and young adults could struggle in the future to find care for their aging parents, and tomorrow’s entrepreneurs may struggle to find enough workers to grow their businesses to their full potential.

Immigrants also fill niches in the labor market, typically at the higher and lower ends of the skills spectrum. Nationally, immigrants are more likely to hold an advanced degree than are their U.S.-born counterparts. They are also more likely to have less than a high school education.[28] Uniquely, this allows them to fill critical shortages in the labor market at both ends of the salary spectrum. Undocumented immigrants, in particular, largely work in the positions an aging and more educated U.S.-born workforce is unable to fill, such as food production, caretaking, and construction.

In New Mexico, immigrants account for more than 37% of the state’s fishers, farmers, and foresters, and 18% of employees in the construction industry.[29] The occupations with the highest shares of foreign-born employees in New Mexico are janitors or building cleaning (25%), cooks (24%), and as commercial drivers (19%). The industries in New Mexico with the highest shares of foreign-born employees are construction (23%), restaurants or other food service (22%), and higher education, including junior colleges (17%).

Immigrants also do some of the most dangerous jobs in the workforce. Some 65,000 immigrants are serving on active duty in the U.S. military. Perhaps more importantly, as the nation struggles to recover from the economic recession brought on by the global pandemic, immigrants are keeping our communities safe and running and helping to keep afloat vital businesses. Nationwide, immigrants are disproportionately employed as “essential” workers, meaning they work in frontline industries. In New Mexico, where immigrants make up about 13% of our overall workforce, they are especially likely to be working in the cleaning industries that are helping keep our hospitals and nursing homes safe.[30] New Mexico’s immigrants are an active and much-needed segment of the state’s labor force and without them our economy would be less productive and dynamic.

Immigrants Have Been Left Out of Many COVID-19 Relief Programs

Though immigrants are an important part of the cultural and economic fabric of our state and a key part of the workforce that is keeping New Mexico running during this crisis, they’ve largely been left out of relief efforts. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act excluded millions of immigrants from its benefits.[31] This not only leaves many New Mexico workers, families, and children struggling, but could have serious detrimental impacts on our state and local economies. Furthermore, these workers often lack access to benefits like paid sick leave and health insurance.

In order to provide financial relief directly to families, the CARES Act included rebate checks of $1,200 for individual tax filers ($2,400 for joint filers), and an additional $500 for every child under age 17, with rebates gradually reduced for single taxpayers with incomes over $75,000, heads of households making more than $112,500, and joint filers with incomes over $150,000.[32]

This is important and necessary assistance for many New Mexico families, but many immigrant families are left out of this relief because in order for a household to receive a rebate, each adult listed on the tax return must have a Social Security number (SSN), and the additional $500 for each child is only available if the child has an SSN. This provision meant many New Mexico workers and their families were ineligible for rebate relief. Because many families are mixed-status, this deprived U.S. citizens of relief as well. Due to this provision, more than 30,000 New Mexico adults and more than 38,000 New Mexico children were denied more than $55 million in recovery assistance. This also means that money will not be circulating in New Mexico’s economy.[33]

While both the state and federal government have taken steps to support workers who have lost income or their jobs since the pandemic began through improvements in the unemployment insurance (UI) system, immigrants who are not work-authorized or who lack documentation are not eligible for UI benefits. Immigrant workers who are eligible must have an SSN or valid work authorization when they apply for UI, while they are receiving UI benefits, and during the base period that states use to determine whether laid-off workers have earned enough wages to qualify for UI benefits. This can leave out some DACA and temporary protected status (TPS) recipients and applicants, as well as undocumented workers. This, despite the fact that, according to a recent report, New Mexico’s immigrants have contributed approximately $58 million to the state’s UI program through payroll deductions over the last ten years.[34]

The negative impact of this aid exclusion is massive for New Mexico workers, families, and communities. More than 16,400 of New Mexico’s low-income workers use an ITIN to file and pay their income taxes. Given that the New Mexico unemployment rate in August of 2020 was higher than 11%,[35] nearly 2,000 New Mexico immigrant workers could miss out on the roughly $315 in state unemployment insurance benefits per worker, per week.[36] This means more than $585,000 in state UI benefits is not flowing to immigrants in New Mexico who have lost their jobs due to the pandemic. The economic stakes may be much higher, as these estimates only take into account workers with ITINs, even though some immigrant workers without ITINs may have also become unemployed due to the pandemic. Lastly, immigrants are overly represented in industries that have been disproportionately impacted by the global pandemic, such as the hospitality industry.

As the nation continues to grapple with the ongoing health and economic crises, policymakers must adopt relief measures that include all immigrants in order to ensure that all of our communities can survive through and thrive beyond the pandemic.

Immigration Law: An Elusive Path

U.S. immigration law is complex and confusing to those who attempt to use it. Immigration to the United States on a temporary or permanent basis is generally limited to three routes: employment, family reunification, or humanitarian protection. Each of these possibilities is highly regulated, and subject to numerical limitations and eligibility requirements. Immigration also takes time – often years or decades – and money. For example, to apply to adjust one’s immigration status and become a lawful permanent resident, the currently filing fee per person is $1,225, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Unauthorized immigrants who want to become citizens cannot just “get in line.” The immigration system is complex and laws remain outdated, cumbersome, and rather restrictive. These issues have been a factor in the increase in immigrants here without documentation.

Our current immigration system has not kept pace with the legitimate needs of our country. It does not work for families who are trying to reunite (many of whom face wait times that can last many years, or even decades); it does not work for businesses that need workers in order to meet the needs of American consumers; and it does not work for immigrants – laborers, entrepreneurs, and others – who want to play by the rules, earn a good living, and give their children a shot at a brighter future. Our current immigration system also doesn’t work for the American public, who rely upon the economic contributions of immigrants in all aspects of our lives. In short, the immigration system has long failed to reflect the realistic needs of American society, American businesses, and American families.

Policy Priorities: Removing Barriers so All New Mexico Immigrants can Thrive

While immigration is largely a federal issue, state and local policymakers can take key steps to better integrate immigrants – including immigrants who are undocumented – into the mainstream economy and foster well-being for everyone. Removing barriers would allow all New Mexico residents to access economic opportunities, which would allow them to earn higher wages, spend more at local businesses, and contribute more in the taxes that fund our schools and other investments that are critical to a prosperous New Mexico.

These common-sense solutions include granting access to COVID-19 relief programs, enacting fair tax policies, expanding access to higher education, and enacting stronger worker supports. These are reasonable steps to maximizing immigrants’ contributions to New Mexico and ensuring that all families in the state have the opportunities they need to thrive.

Enact Inclusive COVID-19 Relief Policies

New Mexico’s state and local governments should do what they can to assist those left out of federal relief in order to ensure that all New Mexico workers, families, and communities can survive through and thrive after this crisis.

- Expand eligibility and funding for the General Assistance Program to include undocumented residents, and others who do not qualify for federal relief.

- Create a new emergency assistance fund for New Mexico residents who are ineligible for other forms of federal or state relief, similar to funds created in Minneapolis, California, and Oregon.

- Create a basic health plan or Medicaid buy-in plan that is available to all residents, regardless of immigration status.

- Increase the state SNAP supplement and expand it so it provides a minimum benefit to families who are financially eligible but do not qualify for federal SNAP due to immigration status.

- Ensure language-appropriate information is available to non-English speakers – information on what benefits are available and how to apply for them, including having non-English application forms.

- Provide information to immigrant communities about public charge and encourage families to enroll their U.S.-born children who qualify for safety net benefits.

Enact Equitable Tax Policy

New Mexico’s Legislature can restructure the tax system so it is more fair for all, as well as more inclusive of immigrants, by providing state-level tax credits to promote economic security and recovery from the recession, and to improve health and well-being for all hard-working families.

- The state’s Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC) is a proven poverty-fighting tool, but it leaves behind too many immigrant workers earning low wages. This tax credit should be expanded to taxpayers filing with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN).[37]

- The state’s Low-Income Comprehensive Tax Rebate (LICTR) should be increased and indexed to rise with inflation. As this rebate has not been increased in more than two decades, this would provide crucial relief for all New Mexico families earning low incomes.

- A new state-level Child Tax Credit should be enacted for families with children.

Remove Barriers to Higher Education

New Mexico has underfunded its public higher education institutions for decades,[38] which has led to enormous tuition increases. This is especially problematic for low-income students, students of color, and immigrant students. The state should enact policy changes to ensure every New Mexican has equal access to higher-educational opportunities.

- Expand to immigrant students the Opportunity Scholarship, which established tuition-free higher education in the state’s two- and four-year institutions.

- Make the New Mexico Lottery Scholarship need-based. This is the state’s largest financial aid program, but it is merit-based. That leaves just 31% of state-funded financial aid as need-based. The national average for need-based aid is 76%.[39]

- Replenish the College Affordability Fund, which provides financial assistance, regardless of immigrations status, to low-income students who do not qualify for the Lottery Scholarship because they attend part-time or are older. More than $75 million was drained from this fund to cover other priorities during the last recession and very little of the funding has been replaced.[40]

Promote an Inclusive Workforce

The state could enact several policies that would benefit many New Mexico workers and improve child and family well-being.

- Enact and enforce policies to prevent wage theft and add more investigators to the Department of Workforce Solutions to deal with the issue, which disproportionately impacts immigrant workers.[41]

- Eliminate exemptions for the state minimum wage for those sectors where immigrants tend to be overrepresented, including dairy and farm workers.

- Ensure that all workers can earn paid sick leave. The lack of paid sick leave is most common in low-wage jobs, where immigrants are over-represented. With almost half of all workers unable to accumulate paid sick leave, New Mexico has the highest percentage of workers lacking paid sick days in the U.S.[42]

Conclusion

New Mexico’s immigrant population is diverse, integral to our state’s history, and provides significant contributions to our communities. Regardless of how they came here, immigrants contribute to our culture, society, and economy – especially right now amidst our nation’s public health crisis. All New Mexicans are likely to benefit from policies that remove barriers to opportunity for immigrants and treat aspiring citizens as valued members of our communities. Treating our immigrant students, workers, and colleagues the way we want to be treated is essential to creating a thriving economy and stronger future for our state.

We can only build a stronger New Mexico if our policymakers are willing to champion equitable policies, cast votes that prioritize all families, and ensure the state consistently provides the revenue needed to make these investments over the long term for all New Mexicans. If we make this commitment, we can ensure a brighter future for our immigrant families and children who call the Land of Enchantment home.

Download this report (Feb. 2021; 20 pages; pdf)

Endnotes

[1]. Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R.G., Immigrant America: A Portrait, Third Edition, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006; “The Economic Benefits of Immigration,” Berkeley Review of Latin American Studies, 2013; “Immigration in the United States: Recent trends and future prospects,” Maylasian Journal of Economic Study, 51(1), 69-85 (2014); and “Immigration in American Economic History,” Journal of Economic Literature, 55(4), 1311-1345 (2017)

[2]. “Immigration in the United States: Recent trends and future prospects,” Maylasian Journal of Economic Study, 51(1), 69-85 (2017)

[3]. “Immigration in American Economic History,” Journal of Economic Literature, 55(4), 1311-1345 (2017)

[4]. Ross, M.C., Immigration Reform: Proposals and Projections, NOVA Science Publishers, 2013; and Jawetz, T., “Immigration Reform and the Rule of the Law,” testimony before the Border Security and Comprehensive Immigration Reform Council, Center for American Progress, Feb. 15, 2019

[5]. “Gifts of the Immigrants, Woes of the Natives: Lessons from the Age of Mass Migration,” The Review of Economic Studies, 87(1), 454-486 (2020).

[6]. “The Economic Benefits of Immigration,” Berkeley Review of Latin American Studies, 2013

[7]. “The Impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement on Immigrant Health: Perceptions of Immigrants in Everett, Massachusetts, USA,” Social Science & Medicine, 73(4), 586-594 (2011)

[8]. FactFinder Population Estimates, U.S. Census, 2018

[9]. State Immigration Data Profile, Migration Policy Institute, 2018

[10]. Ibid

[11]. Rise, Peak, and Decline: Trends in U.S. Immigration 1992–2004, Pew Research Center, 2005

[12]. “U.S. unauthorized immigration population estimates by state, 2016,” Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends, Feb. 2019

[13]. State Immigration Data Profile, Migration Policy Institute, 2018

[14]. U.S. Census, 2010

[15]. “Immigrants and the Economy in New Mexico,” New American Economy, 2018

[16]. Ibid

[17]. Ibid

[18]. Undocumented Immigrants State & Local Tax Contributions, Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy (ITEP), March 2017

[19]. “Property Taxes and Residential Rates,” Real Estate Economics, 36(1), 63-80 (2008)

[20]. Estimated developed by NMVC using the average salaries in NM for the following professions: public defender ($53,856), police officer ($52,500), and teacher ($29,381)

[21]. “Fear vs. Facts: Examining the economic impact of undocumented immigrants in the U.S.,” Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 39(4), 111-135, Western Michigan University, 2012

[22]. “Approximate Active DACA Recipients as of September 30, 2019,” DACA Population Receipts since Injunction, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), 2019

[23]. “The State-by-State Economic benefits of Passing the Dream Act,” Center for American Progress, Oct. 2017

[24]. “Immigrants and the Economy in New Mexico,” New American Economy, 2018

[25]. The Economic Case for Welcoming Immigrant Entrepreneurs, Ewin Marion Kauffman Foundation, March 2014

[26]. “Immigrants and the Economy in New Mexico,” New American Economy, 2018

[27]. “Population Projections,” Geospatial and Population Studies (GPS), University of New Mexico, July 2000 (GPS uses a standard cohort component method based on the demographic balancing equation: Popt = Popt-1+ Births – Deaths + Net Migration)

[28]. “Immigrants and the Economy in New Mexico,” New American Economy, 2018

[29]. Ibid

[30]. Ibid

[31]. Essential but Excluded: How COVID-19 Relief has Bypassed Immigrant Communities in New Mexico, New Mexico Voices for Children (NMVC), April 2020

[32]. “CARES Act Includes Essential Measures to Respond to Public Health, Economic Crises, But More Will Be Needed,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), 2020

[33]. NMVC analysis of data from the U.S. Census American Community Survey, ITEP, and the Pew Research Center

[34] “Unemployment Insurance Taxes Paid for Undocumented Workers in NYS,” Fiscal Policy Institute, May 2020

[35]. Workforce Connection, NM Department of Workforce Solutions, Sept. 2020

[36]. Monthly Program and Financial Data, average benefits from week of 8/31/20, US Dept. of Labor

[37]. “Expanding New Mexico’s Best Anti-Poverty Program,” NMVC, Jan. 2020

[38]. Improving College Affordability to Support New Mexico’s Education, Workforce, and Economic Goals, NMVC, 2018

[39]. “NM’s Lottery Scholarship is not targeted to the students who need it the most,” NMVC, Feb. 2018

[40]. “Advancing Equity in New Mexico: College Affordability,” NMVC, June 2019

[41]. Mexican Immigrants and Wage Theft in New Mexico, Somos Un Pueblo Unido, Aug. 2013

[42]. “Valuing Families at Work: The Case for Paid Sick Leave in New Mexico,” NMVC, Aug. 2019