Link to the fact sheet (Jan. 2019; 2 pages; pdf)

By Armelle Casau, Ph.D.

Introduction

States that graduate more college students and ensure that their workers have the skills needed for 21st century jobs have stronger and more competitive economies, higher wages, lower unemployment rates, and lower poverty rates.1 But New Mexico has not been focused on improving access to post-secondary credentials for lower-income students and older adults – including many parents with young children – that would help lead to a more broadly shared prosperity. Rather, the state is ignoring long-term economic demands, choosing, instead, to continue to be a low-wage state with the highest long-term unemployment rate, have the highest poverty rate among the employed, and have the second worst student loan default rate in the nation.2

There are several reasons for this, but the primary issues covered in this report are these: the state has drastically cut funding to its public universities and colleges, which has led to large tuition increases; the state’s financial aid is misdirected toward students who do not need it in order to complete a degree; the need-based College Affordability Fund has been drained to pay for other unrelated priorities; and, the need-based financial aid that is available is insufficient. Too many adults are left with little choice but to go into debt or give up on attending college. To strengthen our economy and our families by developing our workforce, we need to make adequate, strategic investments in our public universities and colleges to keep them affordable. We also need to make our largest state-funded financial aid program – the Legislative Lottery Scholarship – need-based so we focus on the students most in need of support to succeed instead of the students who are already likely to succeed. In addition, we should replenish the College Affordability Fund and improve grants to better support part-time and older students wanting to earn credentials that can improve their families’ economic security as well as our workforce.

Higher Education Cuts In New Mexico Have Been Drastic

New Mexico has underfunded public higher education institutions for years. State funding for higher education is 34 percent lower now than it was in 2008, when looking at inflation-adjusted state spending per full-time student equivalent (FTE) – down from $14,104 in 2008 to $9,313 in 2018 (as indicated by the blue line in Figure I), according to a 2018 report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). That nearly $5,000 drop in per-student FTE funding since the start of the recession ranks New Mexico second worst in the nation for such funding cuts. Partly as a result of these funding cuts, tuition and fees at New Mexico’s public four-year institutions have increased, on average, by 38 percent since 2008 on a per-student FTE, inflation-adjusted basis – increasing from $5,023 in 2008 to $6,921 in 2018 (as indicated by the orange line in Figure I).3

Meanwhile median household incomes have remained fairly flat over that time period. Similar increases in tuition have been enacted at the state’s two-year community colleges as well.4

Even the state Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) has noted the problem of college affordability, stating in a 2017 evaluation report, “Cost of higher education remains a concern because decreasing state support generally leads to increased tuition.”5 Other states have also observed that declining state appropriations have led to tuition increases at public higher education institutions.6

The consequence of higher tuition is that students and families are bearing more and more of the cost of public higher education. College education is becoming less and less affordable for students of limited means, including many students of color. Adults of color in New Mexico have faced the most barriers to higher education, with only 21 percent having an associate’s degree or higher. New Mexico ranks poorly in the nation on this indicator.7 In 2017, average tuition and fees at public four-year institutions in New Mexico accounted for 20 percent of the median household income for Blacks and 17 percent for Hispanics, while it accounted for just 12 percent of the median household income for non-Hispanic Whites.8 And with college credentials becoming more out-of-reach, more and more employers are unable to find enough workers with the necessary college experience and credentials (see sidebar).

Moving forward, New Mexico needs to raise sufficient revenue to adequately invest in its higher education institutions.

The workforce is underdeveloped

More and more, 21st century jobs require at least some college education. But, in 2016, more than a third (36 percent) of working-age adults (25 to 64 years of age) in the New Mexico labor force had been unable to attain either a high school diploma or equivalent, or any education beyond that. Another third (34 percent) had earned a high school diploma or equivalent and had some college, but had been unable to earn a four-year degree. The final third (30 percent) had a four-year degree or higher.9 It’s been estimated that between 2014 and 2024, only 12 percent of job openings in New Mexico will be for workers with only a high school credential or less, while 48 percent of job openings will be for workers with more than a high school credential but less than a four year degree, and 40 percent will be for workers with a four-year degree or more.10 Without the proper workforce balance, New Mexico’s economy will suffer.

Workforce development is not just important for our state’s economy, but also for our families since many adults with lower educational attainment are stuck in low-wage occupations that don’t provide family economic security. Not surprisingly, New Mexico ranks worst in the nation in the percentage of working families that live in poverty (earning below 100 percent of the federal poverty level, or FPL) or are low-income (earning below 200 percent of FPL).11 Since increasing the educational attainment and the income of parents also positively impacts their children’s educational success and overall well-being, workforce development is a two-generational strategy that would serve New Mexico well. This is particularly important as the state ranks second worst in child poverty nationwide.

Employers need workers with more education and skills

A 2014 statewide survey found that, on average, 47 percent of employers had difficulty finding qualified applicants and specifically, 25 percent of them had some difficulty finding applicants with the needed educational level for the position. Looking at future employment needs, the survey found that the top three job categories that will need the most employees will require some college course work, occupational certificates, or associate’s degrees. Conversely, the category with the highest decrease in projected need was for workers with no high school diploma or equivalent.12

New Mexico Does Not Prioritize Students Who Cannot Attend College without Financial Aid

Less than one-third of state aid is targeted to students in need

While college is becoming harder and harder to afford for families of limited means, the financial aid that New Mexico provides is not well targeted to help those families who most need it. Prior to the early 1980s, virtually all state-funded financial aid across the nation was need-based.13 Over the past few decades, some states – including New Mexico – have shifted largely towards merit-based aid. Currently in New Mexico only 31 percent of the state-funded financial aid is need-based, compared with the national average of 76 percent (see Figure II), when looking at state-funded financial aid dollars per FTE undergraduate student.14

As 25 states target 95 percent or more of their state financial aid to need-based students, New Mexico is behind the curve nationally. With three of those states being Texas, Arizona, and Colorado, New Mexico is also behind the curve regionally.15 Overall, New Mexico does spend more money on financial aid per FTE undergraduate student than the national average and it also does rank near the national average on the proportion of state financial aid funding spent relative to overall spending for higher education.16 But the vast majority of the financial aid New Mexico provides is not need-based and hence not targeted to those who need it most – and low-income students suffer the consequences.

Many low-income students struggle to afford basic necessities and experience insecurity in housing as well as food, with students at two-year institutions more likely to suffer than students at four-year institutions.17 Black, Hispanic, and Native American college students, as well as older students, also have higher unmet financial needs than do their White peers.18 This inability to meet basic needs makes it difficult for students to persist in college and gain the credentials that can lead to economic security. With New Mexico’s lack of focus on need-based state aid and its high poverty rates, it is not surprising that the state fares poorly when it comes to the rate of low-income students enrolled in college. New Mexico’s estimated college participation rate for students from low-income families is only 22 percent, compared with the national average of 34 percent. The highest-ranking state has a low-income student participation rate of 56 percent.19

Need-based state aid funding is insufficient

New Mexico provided almost $105 million from the major state-funded financial aid programs to nearly 51,000 students in FY17.20 Figure III outlines the ten primary state-funded financial aid programs (including grant, scholarship, and work-study programs) for undergraduate students enrolled in New Mexico public universities and colleges. Not included in this list are very small financial aid programs like the Vietnam Veterans program that impacted very few students in FY17. These ten major programs represent nearly 99 percent of the state’s total financial aid funds ($104.9 million out of $106.5 million) and more than 97 percent of the total number of all students who receive state aid (50,999 out of 52,477).

Figure III shows how little state funding is targeted to need-based financial aid programs. Out of the nearly $105 million in state dollars spent on financial aid, only 18 percent ($19.3 million) was spent on programs that are solely need-based. Data from previous years show similar funding patterns across these programs. While about 40 percent of all state aid awardees received solely need-based aid awards, the average award amounts for need-based state financial aid programs ($947) was a third lower than award amounts for merit-based state aid programs ($2,799). The full cost of college attendance (COA) ranges widely. At CNM, the state’s largest two-year institution, the COA is $13,272 (of which $1,340 goes to tuition and fees) and at UNM, the state’s largest four-year institution, the COA is $19,542 (of which $6,644 goes to tuition and fees).

Lottery Scholarships account for the majority of state’s aid

In FY17 two-thirds of our state financial aid dollars came through the merit-based Legislative Lottery Scholarship (see Figure IV) – New Mexico’s largest state-funded financial aid program – and the other two accompanying merit-based Lottery Scholarship programs, the bridge Lottery Scholarship (which covers the first semester of college not covered by the regular Lottery Scholarship) and the Disability Lottery Scholarship (which has lower attendance and completion requirements for students with disabilities). These three scholarships are the primary reason so little of our state’s financial aid funding is need-based. And since the Lottery Scholarships are only available to full-time students who have very recently earned their high school diplomas or equivalent, it leaves older and part-time students out even though these students constitute a majority of the student population. Many of these students have children to care for and are looking for credentials to increase their families’ economic security.

Research shows that merit-based scholarship programs benefit middle- and upper-income students most – since they are more likely to have had access to greater educational resources and the experiences that lead to increased academic success. Because these students have other financial resources, these scholarship programs do not significantly increase college graduation rates for those types of students.21 Conversely, need-based grants for low-income students have been shown to help with college access, persistence, and graduation.22 Making the New Mexico Lottery Scholarship programs need-based would maximize the outcomes they were intended to have – increased access to college, reduced students’ financial burden, and improved educational attainment in New Mexico.23

Merit-based lottery scholarships transfer wealth upward

Merit-based lottery scholarships result in a transfer of wealth from those with lower incomes to those with higher incomes. Lotteries are disproportionately played by lower-income people who spend a higher percentage of their income on game tickets. This regressive nature is worsened by the fact that merit-based scholarships tend to fund the education of middle- and high-income students who are much more likely to be able to afford college without financial aid.24 Studies have found that the Georgia HOPE Scholarship – a merit-based lottery scholarship like New Mexico’s – dis-proportionally helped upper-income students and had a greater impact on college choice than on college attendance.25 In addition, since stagnating lottery revenues in New Mexico have not kept pace with scholarship demands and tuition increases, the state has enacted policy changes that make it harder for low-income students to access, retain, and benefit from the scholarship. These changes include an increase in full-time credit hour requirements and significantly decreased tuition coverage. Both of these changes are more likely to hurt students from low-income families than students from middle- and high-income families.

Too much state aid goes to students from high-income families

Too much state funding, including the Lottery Scholarship programs, goes to students from high-income families, many of whom are more likely than their lower-income peers to be eligible for substantial private and institutional merit-based scholarships. As seen in Figure V, 21 percent ($21.8 million) of New Mexico’s state-funding for the financial aid programs listed in Figure III goes to students from families that earn more than $80,000 per year, which is nearly double the state’s median household income of $46,744.26 More than 15 percent of funding ($15.7 million) goes to student from families earning more than $100,000 per year. This Figure excludes the $1.4 million in state funding spent on Competitive Scholarships for out-of-state students, since those are not available to New Mexico students. New Mexico families making $100,000 or more per year can more easily afford college costs for their children than low- and middle-income families can.

Looking specifically at the New Mexico Lottery Scholarships, nearly 27 percent of that funding (or $18.8 million) went to students from families earning more than $80,000 a year in FY17. Specifically, more than 19 percent of that funding ($13.6 million) went to students from families earning more than $100,000 per year. All of this indicates that the state is spending tens of millions of dollars every year subsidizing college costs for high-income families. This makes little sense in a state with high poverty rates and relatively low tuition costs. New Mexico would have more success generating good-paying jobs and improving our economy if we concentrated our efforts on the students who would be unable to attend college without financial assistance instead of on those who would be able to attend college without it. Sliding-scale state assistance can be warranted for some families making $80,000 a year, particularly those with more than one child in college. Options for state aid with sliding scales are listed at the end of the report.

New Mexico could do a better job of tracking where state aid goes

Unfortunately, we don’t know the full extent of the impact of the state’s financial aid decisions because 21 percent of our state aid funding ($21.4 million, including $15.0 million from the Lottery Scholarships) goes to students who did not fill out a FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) form. These students are more likely than not to be from middle- or high-income families. A recent nationwide survey showed that of the undergraduates who did not apply for financial aid (including federal aid), the top two cited reasons for not applying were that they could afford college without aid (43 percent) and they thought they were ineligible (44 percent), usually because of their family income.27There are indeed some low-income students who do not fill out a FASFA form because they do not know about it, are worried about going into debt, or are undocumented and not eligible for federal financial aid.28 Requiring students to fill out a FAFSA form (or a similar and simplified state version for undocumented and first-generation students) in order to receive state financial aid would provide a clearer picture of who is benefiting from state funding. In addition, it would give more financial aid options to students who have not historically filled out a FASFA form, and likely bring in some additional federal monies, like Pell Grants, that generate economic activity in the state.

Other states with long-standing merit-based lottery scholarships29 (denoted by the yellow boxes in Figure VI, in addition to the orange boxes indicating New Mexico) rank near the bottom when looking at the percentage of their state funding that is need-based.30 These states also rank poorly in key education and economic-related indicators, including adults with at least some college, median household income, adult poverty rates, and student loan default rates.31

The State’s Student Financial Aid Awards Are Insufficient

Lottery Scholarships now cover only a fraction of tuition costs

Whether merit- or need-based, Mew Mexico’s financial aid amounts are too low. When financial aid awards are insufficient to cover college costs and living expenses, it’s the low-income students who suffer the most.

Lottery scholarship demand has continued to outpace the amount transferred to the scholarship fund from lottery ticket sales in New Mexico. Over the past couple of years, the state has not appropriated additional funding to fully cover average tuition costs (which fall under three sectors: two-year community colleges, four-year comprehensive universities, and four-year research universities) at 100 percent, as the scholarship was originally intended to do (although this full tuition coverage was never legislated). Starting in FY15, the share of tuition covered by the scholarship dropped to 95 percent, then to 90 percent in FY16-FY17, and down to 60 percent in FY18 due to insufficient funding.32 Beginning in FY19, the Lottery Scholarship will only cover a low flat amount of sector-based tuition, which unfortunately won’t automatically rise with inflation or tuition increases.

Per semester, the Lottery Scholarship will now cover only a portion of current average sector-based tuition costs: $1,500 (about 42 percent) for four-year public research universities; $1,020 (about 35 percent) for four-year public comprehensive universities; and $380 (about 45 percent) for two-year public community colleges.

Depending on available lottery funds, the amounts might be a bit higher, but it’s not likely to ever again reach the amounts needed to cover full tuition costs.

While students from high-income families can absorb that drop in support, this is a problem for low-income and some middle-income students who are sensitive to price fluctuations and who depend on this scholarship to attend college. Studies have shown that even small tuition increases of $100 can, without additional aid, be enough to keep low-income students from enrolling in, or persisting with, college. Conversely, for every $1,000 in college tuition reduction, the college-going rate for high school graduates increases by about 5 to 7 percentage points.33

New Mexico could increase the impact of the scholarship if it distributed sufficient aid to students who need it most instead of capping awards and distributing smaller amounts of aid to as many students as possible, including high-income students. The inability to pay for college costs is one of the key reasons low-income students drop out of college. By making the Lottery Scholarship need-based and limiting the number of students who can access it to those who demonstrate financial need, we can once again cover tuition at 100 percent for those students and help increase college completion rates.

The state’s need-based College Affordability Fund has been depleted

While making the Lottery Scholarship need-based would dramatically increase the percentage of our state-funded financial aid that is targeted at the students who need it the most, there are other financial aid programs that need attention since the Lottery Scholarship is not accessible to students who are part-time or have been out of high school for a while.

New Mexico has the state-funded, need-based College Affordability Fund that provides up to $1,000 per semester (depending on need and course load) for low-income adults whose enrollment can be limited to half-time. Unfortunately, this fund is now depleted. In 2007, the fund had $95 million in reserves but $68 million was removed in 2010 and another $5 million was taken out in 2016 to fund other, completely unrelated, state priorities. While $1.5 million was added back in 2017 to help keep the fund solvent for another year, it now lacks enough funding to cover the average disbursements of $2 million per year for FY19.34

This fund is a crucial component of financial aid for low-income, older or part-time students and needs to be replenished. But even when the fund had sufficient reserves it did not serve enough students and it only provided a fraction of what was needed to cover tuition for those attending four-year universities. With 51 percent of college students attending public New Mexico institutions on a part-time basis, additional funding needs to be appropriated to serve more low-income, part-time students. More funds are also needed to provide higher award amounts.

New Mexico also has the need-based Student Incentive Grant (SIG), which disbursed $11.1 million in FY17. This grant used to get additional funding from the federal Leveraging Educational Assistance Partnership (LEAP) program, which provided matching federal dollars for state need-based financial aid. Unfortunately, the LEAP program was eliminated in 2011 as part of the continuing resolution that was passed to avert a federal government shutdown. The SIG program provides a maximum award of $2,500 per year and, just like the College Affordability Grant, it serves low-income students, including those who can only attend college half-time. And like the College Affordability Grant, this program also provides insufficient aid for many low-income, older or part-time students enrolled in four-year institutions.

In New Mexico, state financial aid accounts for 18 percent of the total financial aid that students rely on to help pay for college (see Figure VII). Another 25 percent of the aid students receive comes from federal Pell Grants and the largest share – 39 percent – comes from public and private loans. The “other” category in Figure VII (at 16 percent) includes federal work study and Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants, private grants and gifts, institutional grants and gifts, Native American tribal aid, and other gifts and scholarships from both within and outside of New Mexico. That category provides more than $113 million in aid but, as with state aid, a large portion – 40 percent ($45 million) – goes to students from families earning more than $80,000, including 11 percent ($12 million) to students from families earning more than $100,000 and to students who did not fill out a FAFSA form.

Pell Grants are insufficient and shrinking

Some lawmakers hold the misperception that our state does not require more need-based financial aid because low-income students receive Pell Grants. Pell Grants are need-based federal grants that provide invaluable financial aid for low-income students, are available to students attending college part-time, and can be used to cover living expenses (unlike many other scholarships that can only be used to cover tuition costs). But Pell Grant award amounts are limited – the maximum amount a student could get in the 2017-18 school year was $5,920 – but in New Mexico, the most recently available data show that students only received, on average, about $3,630 in the 2016-17 school year.35

Pell Grants also have decreasing purchasing power. Nationally, looking at constant dollars, the average Pell Grant covered 34 percent of the total cost of college attendance in 1974-75 but since the average award amount hasn’t kept pace with rising college costs, it only covered 16 percent of the total cost of attendance in 2016-17.36 There are also federal proposals to cut back on Pell Grant funding in future years or to freeze maximum Pell Grant awards, meaning the value would further erode over time.

When you factor in living expenses, Pell Grants only cover a small fraction of actual college costs. This is especially true for older and independent students, many of whom are foregoing earnings while in school. Insufficient financial aid impacts college attendance and persistence for low-income students in particular.

The full cost of attendance (COA) ranges widely. At CNM, the COA is $13,272 (of which only $1,340 goes to tuition and fees) and at UNM, the COA is $19,542 (of which only $6,644 goes to tuition and fees).37 Low-income students with Pell Grants still pay, on average, a much higher percentage of their family income on college costs than middle- and high-income families without Pell Grants pay.

Another issue low-income students could face is a policy proposal advanced by some to make the Lottery Scholarships and other state grants “last dollar” or “Pell First,” which means that students would have to use their Pell Grant first to cover tuition costs at public institutions and then use state-funded scholarships like the Lottery Scholarship to make up the difference. If state grants and scholarships are made to be “last dollar,” many students would be unable to use Pell Grants to help pay for living costs.

Other Problems with New Mexico’s Student Financial Aid

Little state aid goes to two-year colleges

Overall, as seen in Figure VIII, for the main state-funded financial aid programs listed in Figure III, 85 percent of the funding ($88.8 million) in FY17 went to four-year institutions while only 15 percent ($15.7 million) went to two-year institutions. This is a nearly six-fold funding difference. New Mexico’s public four-year institutions are more expensive than two-year institutions but the $6,489 in yearly average tuition costs for four-year institutions is only 3.8 times the $1,706 yearly average tuition costs for two-year institutions so tuition costs do not entirely account for this funding imbalance.38

A similar imbalance is seen in the number of students benefiting from state-funded aid programs, with 58 percent of awardees attending four-year institutions and 42 percent attending two-year institutions. Given that 60 percent of all public college undergraduate students in New Mexico are enrolled in two-year colleges, there are imbalances in funding and financial aid award distribution.39

Looking specifically at the combined Lottery Scholarship programs in Figure IX, only 26 percent of Lottery Scholarships recipients were enrolled at two-year institutions and only 7 percent of the Lottery Scholarships funding went to two-year institutions in FY17. Since two-year colleges are more accessible to low-income, working, parent, minority, and rural students than are four-year universities, this also reflects an equity imbalance of the state’s largest set of aid programs.40

Yesterday’s Non-Traditional Students are Today’s Typical Students

College student demographics are changing. College students on average are older, work more hours to afford college and living costs, and are more likely to have children, which makes it harder to go to school full-time. Nationally, 40 percent of college students are over 25 years of age, 26 percent are parents, 51 percent are low-income, and 27 are employed full time.41 But our state financial aid is not geared toward adults and full-time workers. Lawmakers need to take these college student demographics into consideration when setting eligibility requirements for state-funded scholarships so aid programs are more equitably accessible to older and part-time students, including students who have children.

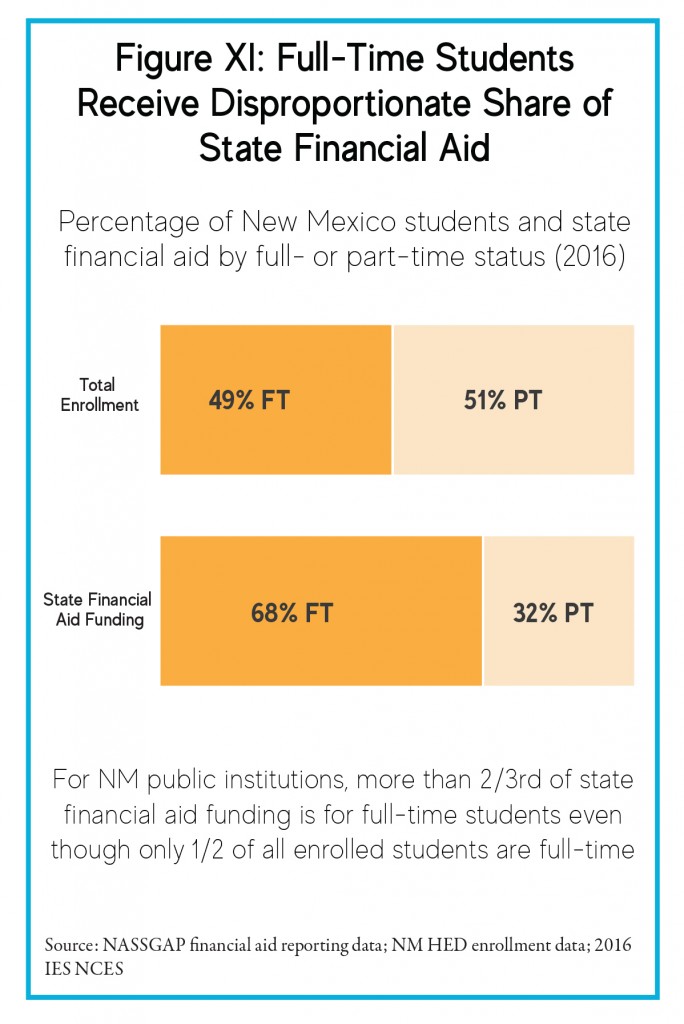

About 51 percent of college students enrolled in New Mexico public colleges and universities are part-time.42 Unfortunately, because our largest state-funded aid program – the Lottery Scholarship – requires full-time college attendance, only one-third (32 percent) of our state aid funding is for students who are part-time (Figure XI). Additionally, only 4 percent of the state aid awards for undergraduates go to students who are enrolled less than half-time.43 This is because nearly all of our state aid requires at least half-time enrollment status. For some students, half-time can be a burden when they have to juggle a full-time job or family obligations. This was found to be the case in Illinois. The Illinois Monetary Assistance Program (MAP) initially only provided aid to low-income, half-time, students. The state changed eligibility requirements to less-than-half-time when a study showed that this helped those students who had to temporarily drop below half-time to stay enrolled.44

More than two-thirds of state aid goes to just two universities

There is another imbalance that negatively impacts students in smaller cities and rural communities. Out of the more than $105 million of state-funded financial aid, 70 percent of the dollars went to only two institutions – UNM and NMSU – out of the 24 public universities and colleges across the state. And even though UNM and NMSU account for only 33 percent of the total student population enrolled in New Mexico’s public higher education institutions, 45 percent of all state-funded financial aid awardees were enrolled in these two institutions.47

New Mexico ranks second worst in student loan default rate

Since so many students have unmet financial needs even with state aid, Pell Grants, and other grants or scholarships, many are increasingly turning to loans to make up the difference. This is especially the case for low-income students since Pell Grant recipients are twice as likely as their peers to take out student loans. There is also a racial and ethnic equity issue since borrowing rates are consistently higher for Black and Hispanic college students than for White or Asian students.48

Loans constitute about 40 percent, on average, of the financial aid that New Mexico students depend upon. Across the state, 44,643 students borrowed $248 million in student loans in FY17 and the average loan debt per student was $5,554. While New Mexico is a low-tuition state and the average loan amount is not as high as in many other states, students in our state have a hard time repaying those loans partly because the economy is still struggling and wages have been stagnant. As a result, New Mexico has a student loan default rate of 18.2 percent, which is the second worst rate in the nation and much higher than the national average of 11.5 percent.49 When adults carry debt, many need to delay buying a home, starting or operating a new business, or starting a family. Many also seek higher wages in other states.50

Endnotes

- A Well-Educated Workforce is Key to State Prosperity, Economic Policy Institute, 2013; America Works: Education and Training for Tomorrow’s Jobs, National Governors Association, 2013-2014

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, long-term unemployment and wage data; American Community Survey, 2017 poverty data; Cohort Student Loan 2014

Default Rate, U.S. Department of Education - Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) 2008-2018 higher education funding and tuition data provided to NM Voices; Unkept Promises: State Cuts to Higher Education Threaten Access and Equity, CBPP, 2018

- Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) Tuition and Fees in Public Higher Education in the West data

- Program Evaluation: Higher Education Cost Drivers and Cost Savings, NM Legislative Finance Committee, 2017

- Hot Topics in Higher Education: Tuition Policy, National Conference of State Legislatures, 2015

- Working Poor Families Project’s analysis of 2016 U.S. BLS data

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) 2017 data provided to NM Voices; Unkept Promises: State Cuts to Higher Education Threaten Access and

Equity, CBPP, 2018 - American Community Survey, educational attainment of NM adults ages 25-64 in the labor force, 2016 1-year estimate

- New Mexico’s Forgotten Middle, National Skills Coalition’s analysis of long-term occupational projections from NM DWS, 2014-2024

- Working Poor Families Project’s analysis of 2016 ACS microdata

- New Mexico Employer Survey, 2014 NM Department of Workforce Solutions

- Trends in Student Aid 2017, College Board, 2017

- National Association of State Student Grant and Aid 47th survey report on state-sponsored student financial aid, academic year 2015-16

- Ibid.

- Trends in Student Aid 2017, College Board, 2017

- Still Hungry and Homeless in College, Wisconsin HOPE Lab, 2018

- CLASP analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2015-16 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study; Developing State Policy that Supports Low-Income, Working Students, CLASP, 2018

- Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States, The Pell Institute, 2018

- NASSGAP Data obtained from the New Mexico Higher Education Department, FY17

- “State Merit-Based Financial Aid Programs and College Attainment,” Journal of Regional Science, 2014

- “Looking Beyond Enrollment: The Causal Effect of Need-Based Grants on College Access, Persistence, and Graduation,” Journal of Labor Economics, 2016

- “Making College Affordable by Improving Aid Policy,” Issues in Science and Technology, 2010

- A Gamble with Consequences: State Lottery-Funded Scholarship Programs as a Strategy for Boosting College Affordability, American Association of State Colleges and Universities, 2014

- “Making College Affordable by Improving Aid Policy,” Issues in Science and Technology, 2010

- American Community Survey, 2017 1-year estimate

- Undergraduates Who Do Not Apply for Financial Aid, U.S. Department of Education Data Point, 2016

- Financial Aid Eligibility Mindsets Among Low-Income Students, National College Access Network, 2016

- A Gamble with Consequences: State Lottery-Funded Scholarship Programs as a Strategy for Boosting College Affordability, American Association of State Colleges and Universities, 2014; A Comparison of State’s Lottery Scholarship Programs,

Tennessee Higher Education Commission, 2012 - National Association of State Student Grant and Aid 47th survey report on state-sponsored student financial aid, academic year 2015-16

- American Community Survey, educational attainment, poverty and median household income 2016 data; Cohort Student Loan 2014 Default Rate, U.S.

Department of Education - NM Legislative Lottery Scholarship Report, NM HED, 2017

- Price Sensitivity in Student Selection of Colorado Public Four-Year Higher Education Institutions, Colorado Department of Higher Education, 2012; College on the Cheap: Costs and Benefits of Community College, University of Texas at Austin, 2014

- NM LFC Fiscal Impact Reports for College Affordability Fund bills

- Distribution of Federal Pell Grants by State 2016-17, US Department of Education

- Indicator of Higher Education Equity in the United States, The Pell Institute, 2018

- Higher Education Cost Drivers and Cost Savings, NM Legislative Finance Committee, 2017

- NM Higher Education Department data

- Ibid

- Policy Matters AASCU A Gamble with Consequences: State Lottery-Funded Scholarship Programs as a Strategy for Boosting College Affordability

- NCES/IPEDS data from Redesigning State Financial Aid to Better Serve Nontraditional Adult Students, CLASP, 2016

- Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, National Center for Education Statistics

- NASSGAP Data obtained from the New Mexico Higher Education Department, FY17

- Redesigning State Financial Aid to Better Serve Nontraditional Adult Students: Practical Policy Steps for Decision-Makers, CLASP, 2016

- Strengthening New Mexico’s Workforce and Economy by Developing Career Pathways, New Mexico Voices for Children, 2014

- Pennsylvania Targeted Industry Program, Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency

- NASSGAP Data obtained from the New Mexico Higher Education Department, FY17

- Indicator of Higher Education Equity in the United States, The Pell Institute, 2018

- Cohort Student Loan 2014 Default Rate, U.S. Department of Education

- Life Delayed: The Impact of Student Debt on the Daily Lives of Young Americans, American Student Assistance survey, 2013; Student Loan Debt and Housing Report, National Association of Realtors, 2017; The Biggest Threat for Startups? Student Loan Debt, EdSurge, 2016.

Download the full report (Jan. 2019; 20 pages; pdf)

Link to the fact sheet (Jan. 2019; 2 pages; pdf)

A Working Poor Families Project report.

The Working Poor Families Project is funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Ford Foundation, Joyce Foundation, and The Kresge Foundation.