by Paige Knight, MPP

by Paige Knight, MPP

December 2020

Download this report (Dec. 2020; 26 pages; pdf)

Acknowledgements

New Mexico Voices for Children is grateful for the research and expertise of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, and the Washington State Budget & Policy Center, all of which provided inspiration, knowledge, and analysis for this report.

A Note About Data: Whenever possible, data are disaggregated by race and ethnicity to provide a preliminary understanding of disparities. Data are not always available for all races, ethnicities, or tribes, which we recognize is problematic given our nation’s long history of cultural erasure. Some rural and tribal areas in New Mexico also tend to be undercounted in U.S. Census data and can be underrepresented in other sources as well. As a result, the statistics throughout this report tell a limited story, and in many cases, the numbers don’t reflect people’s lived experiences. New Mexico Voices for Children is committed to continuing to engage with the communities represented in this data to better understand the stories, voices, and people behind the numbers. We are also committed to both engaging with the communities left out of this data and advocating for better, more accurate, and inclusive data.

Introduction

Our children are New Mexico’s greatest asset, and they and their families should have every opportunity to live, learn, and thrive in healthy and safe communities – regardless of their zip code, skin color, or financial status. Creating thriving communities requires public investments, like quality education that boosts opportunities for all students, economic supports that help working families struggling financially to afford housing and nutritious food, and health coverage to access affordable health care, all of which produce a more prosperous and productive workforce and economy.

Unfortunately, decades of misguided laws and fiscal policies have left the state without the resources needed to make these critical investments, leaving New Mexico’s families and communities of color without the opportunities and supports they need in order to thrive. Inequities exist across lines of race and ethnicity when it comes to educational attainment, health outcomes, income and wealth, and economic well-being. These inequities stem from racism’s harmful legacy and ongoing oppression towards people of color in New Mexico and throughout the nation.

Government actions and policies have reinforced and further widened racial divides in income, wealth, education, and in the workplace. They range from slavery and Jim Crow laws, to the confiscation of tribal land and resources, to a drug-focused criminal justice system, and to red-lining policies, lending discrimination, and the segregation of Black families in lower-value neighborhoods. These policies have all been barriers to equal opportunity – despite the powerful resistance, organization, and advocacy of those facing racism and discrimination.

In order for every child in New Mexico to reach their full potential, our policymakers need to ensure that the policies in place now and in the future are antiracist. In other words, policies need to improve racial and ethnic equity, not cement current inequities in place. Tax policy is a powerful tool that can help advance racial justice because it outlines who pays their fair share of taxes, who doesn’t, and who benefits most from the way the system is structured.

But tax policy – like so many other public policies – has not always been used to advance equity. Instead, it has deepened racial inequities in both the past and present. And although New Mexico’s tax code is not grounded in racial hostility, many of the state’s policies still perpetuate these inequities. It does this by: providing tax cuts that favor wealth – owned overwhelmingly by white households – over the hard-earned wages of New Mexicans; giving more generous hand-outs to big corporations and the well-connected than families struggling financially; and limiting tax revenue at the expense of quality classrooms and other critical public services that build strong communities.[1]

Right now, New Mexicans earning low and moderate incomes – who are primarily families of color – pay a much greater share of their income in state and local taxes than do the state’s highest income earners – who are disproportionately white. And thanks to an overly generous tax deduction, New Mexico taxes the income earned from wealth – which is held overwhelmingly by white households – at a much lower rate than the wages and tips earned by hardworking New Mexicans.

Advancing racial equity through tax policy is an investment in the lives and future of all children. And it’s particularly important in New Mexico because 76% of our children are children of color (Figure I). We can break down the many hurdles our children face by improving how New Mexico raises revenue and funds important public services. At the same time that these changes are helping undo racism’s harmful legacy and ongoing damage they are strengthening all of our communities and the economy.[2]

In order to build a more equitable New Mexico, all of our tax cuts, deductions, credits, and rates need to prioritize hardworking New Mexicans and our communities of color instead of the wealthy and well-connected. This report discusses how past discriminatory policies in both the public and private sector have gotten us to where we are today, the racial and ethnic inequities that still exist in New Mexico and are particularly apparent due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and how tax policy can be improved and used as a tool so all New Mexicans have the resources and opportunities they need to reach their full potential.

History of discrimination and economic oppression

The racial and ethnic disparities that exist in our communities today are not due to happenstance. They are the direct result of institutional and systemic racism and the discriminatory policies that have determined who does and does not have access to income and wealth-building opportunities. Throughout history, people of color have had very little power in all levels of government, which has allowed white lawmakers to set policies that benefited themselves while deepening the challenges that people of color faced, whether those policies were explicitly race-based, or not. These discriminatory policies have occurred in both the public and private sector, including:

- The confiscation of land and resources from Native Americans, along with forced assimilation and displacement.

- The enslavement of Native Americans – known as genízaros – in present-day New Mexico, first under Spanish colonists, then under Mexican rule, and continued when New Mexico became a U.S. territory.

- The kidnapping, transport from their home countries, and enslavement of Black individuals and their families followed by restrictive and racist Jim Crow laws.

- The provision of free land to white male citizens via the Homestead Act of 1862, excluding Native American, Asian, Black, and other families who did not have European ancestry from this wealth-building opportunity.

- The delay in New Mexico’s statehood due to having a predominantly Mexican American and Native American population.

- The creation of the Land Grant Permanent Fund at statehood, when the federal government took land belonging to Native Americans and families holding Spanish land grants and set up a system to funnel revenues generated by those lands to the state.

- Discrimination in housing policies like red-lining, the segregation of Black families in lower-value neighborhoods, and racially restrictive covenants – real estate contracts that prohibited home sales to families of color – (even in Albuquerque) that were designed to maintain the homogeneity of white neighborhoods.

- Discrimination in financing, which has made it harder for borrowers of color to get loans, forcing them to turn to predatory lenders with financially debilitating high interest rates.

- The focusing of our criminal justice system on drug possession and use, over-policing in low-income areas and communities of color, differences in sentencing for similar drugs based on which racial groups use them, and a growing over-reliance on fines and fees to balance state and local budgets.

- Hiring and workplace discrimination, which has made it more difficult to obtain jobs, promotions, and fair pay.

Tax policy is not race-neutral

State statutes do not explicitly mention race or ethnicity, nor are race and ethnicity used to determine a person’s tax liability. But tax policy – like all other policies – is not race-neutral. Tax policy does not need to be intentionally racist to worsen or cement long-standing racial inequities in wealth and power. Racism’s historical legacy coupled with the discrimination and bias that exist today still impact a taxpayer’s income, consumption, and the valuation of their property. Examples of such policies include:

- Supermajority requirements that began in the post-Reconstruction era, when wealthy white landowners in Mississippi passed a constitutional requirement for a three-fifths vote for all state tax increases. This made raising revenue for public investments in schools and other services much more difficult, adding to the barriers that Black people faced then and yet today.[3]

- Property taxes are a primary source of local government revenue, but limits on property tax rates make it much more difficult to provide quality services for communities, like schools, parks, and libraries. The earliest constitutional property tax limits were adopted in Alabama at the end of the 19th century. These limits protected white property owners in the event that African Americans would come to power and try to increase property tax rates to fund education and other measures.[4] Over 140 years later, Alabama’s property tax revenue as a share of its economy is the lowest of any state, severely limiting the ability of local governments to provide quality education and other public services.

- In 1932, the first modern sales tax was adopted in Mississippi in order to reduce property taxes. This change shifted the tax base away from property owners and onto consumers, ultimately benefiting mostly white property owners while increasing taxes paid by Black households that owned little or no property.[5] Sales taxes generally fall hardest on those with the lowest incomes, yet these taxes now comprise a significant amount of the revenue base for many states.

- Property assessments for tax purposes is often a muddied process, and in the rural South during the Jim Crow era, assessors were typically white politicians who often over-assessed property owned by African Americans and under-assessed property owned by white residents. This meant African Americans were taxed more to support public programs and services they were simultaneously denied – or had separate and unequal – access to.[6]

These are just a few examples of the many ways discriminatory actions and policies have inhibited the ability to build generational wealth and have impacted the health and well-being of people of color. These examples also demonstrate how policy is not race-neutral. At every level, policy is producing or sustaining either equity or inequity between racial groups. Unfortunately, too many past and current policies have held families of color back from the same opportunities as white families, and one of the most harmful examples of such consequences is the racial wealth divide.

The yawning racial wealth divide

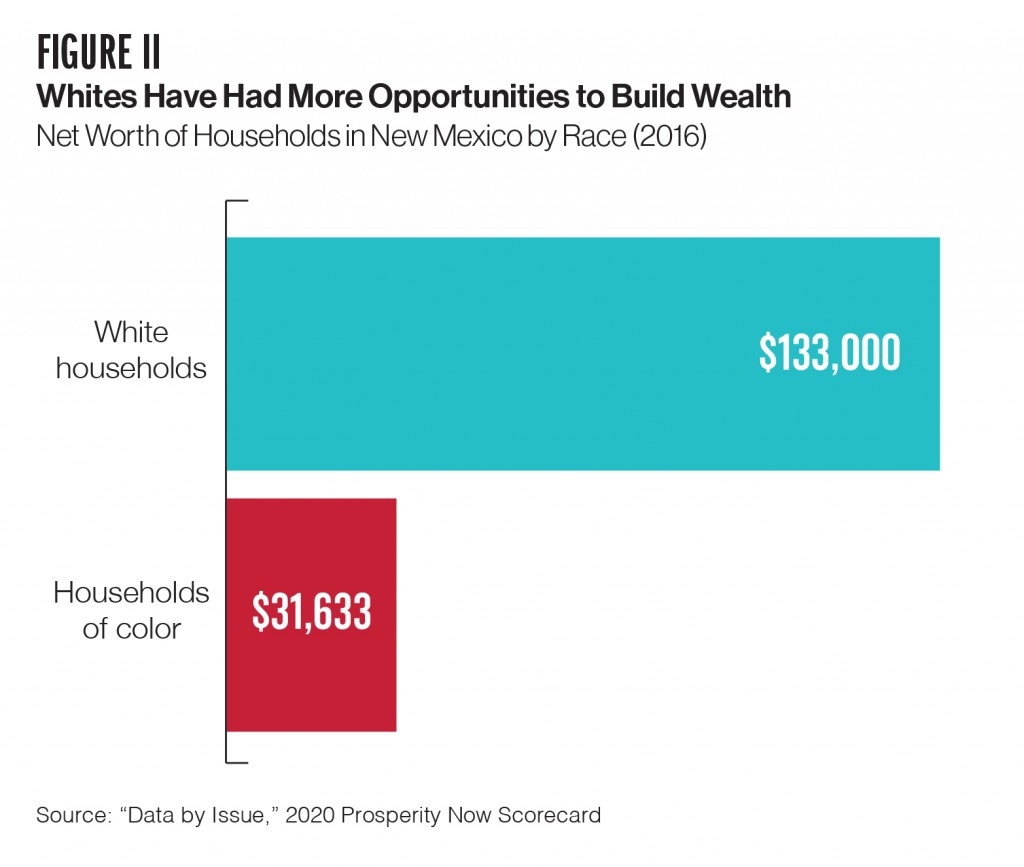

The racial wealth divide is a clear economic illustration of how decades of racial discrimination have resulted in and compounded the disparities we see today in health and economic security across racial and ethnic lines. Simply put, wealth is what you own minus what you owe, and the racial wealth divide is the difference in the net worth of white families and families of color. In New Mexico, white households have a median net worth of $133,000 while households of color have a median net worth of only $31,000 (see Figure II). Nationally, it’s even worse, with white households having ten times the median net worth of Black households and more than eight times that of Hispanic households.[7]

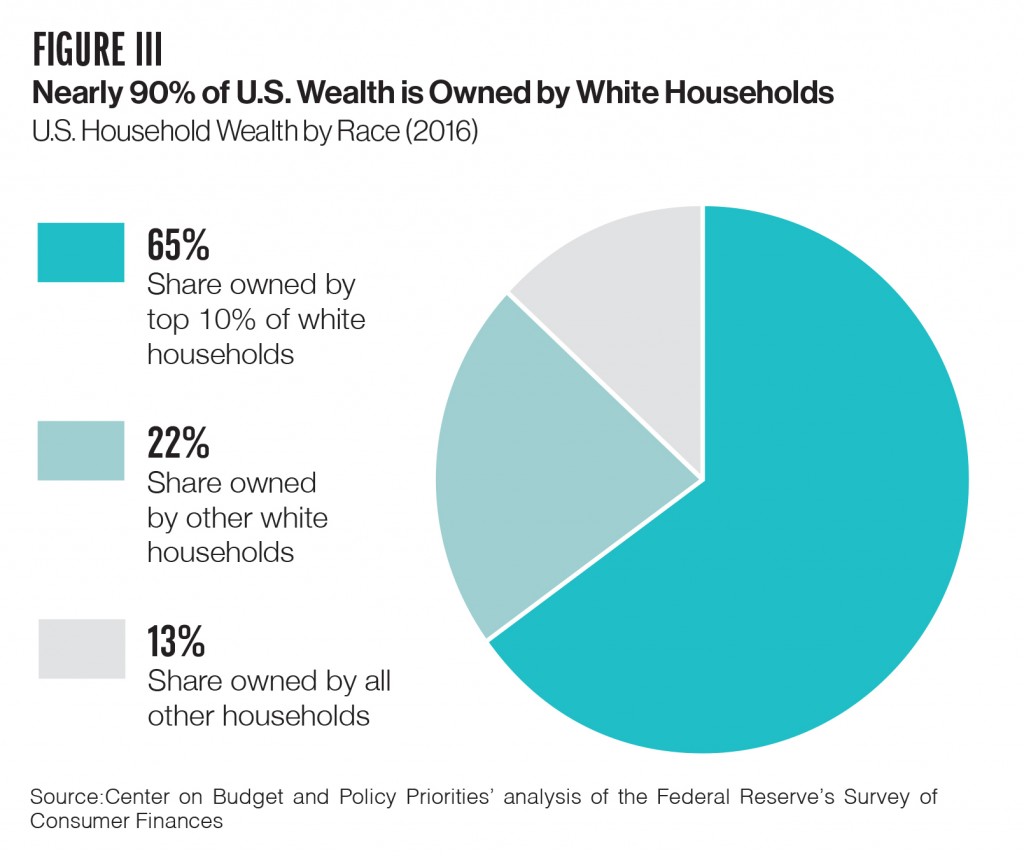

Wealth is important to health and economic security because insufficient wealth means you’re unable to purchase and hold onto your home, unable to obtain high-quality education without having to go into debt, unable to experience financial security, or to weather a crisis like a job loss or a major health challenge. And because wealth accumulates over generations, the divide has only gotten worse over time creating patterns of poverty and wealth that are highly unequal along the lines of race and ethnicity (see Figure III).

Wealth is important to health and economic security because insufficient wealth means you’re unable to purchase and hold onto your home, unable to obtain high-quality education without having to go into debt, unable to experience financial security, or to weather a crisis like a job loss or a major health challenge. And because wealth accumulates over generations, the divide has only gotten worse over time creating patterns of poverty and wealth that are highly unequal along the lines of race and ethnicity (see Figure III).

Home ownership divide

Home ownership makes up about two-thirds of the wealth of an average American household, but, as Figure IV shows, white families in New Mexico are far more likely to own their homes than are families of color. Again, discriminatory policies – such as being denied a loan for a home or business or being denied the ability to live in a certain neighborhood – have led to these disparities. Even today, there’s evidence that prospective Black and Hispanic home buyers are turned down for home mortgages far more often than are white applicants of similar incomes.[8] Another study shows that Black and Hispanic home buyers are far more likely than whites to be charged higher interest rates, even when they have similar financial situations.[9]

Income divide

The ability to accumulate wealth over time increases with higher earnings, where again we can see disparities across different races and ethnicities. The median income for white households with children is $72,200 in New Mexico. As you can see in Figure V, it’s significantly lower for Hispanic, Black, and Native American households with children.

These disparities in earnings are not fully explained by education or occupation, either. Nationally, Black workers experience higher rates of unemployment and receive lower wages than white workers at every education level, and they receive lower wages in every occupation. Discrimination and segregation in hiring, pay, unionization, and employment were common and legal until the 1960s, but structural racism and implicit bias in the labor market persist today and have perpetuated employment and wage disparities.[10]

The racial wealth divide is not an unsolvable problem, but it requires bold, antiracist policy solutions to eliminate it. Tax policy and targeted public investments can help narrow the growing divide.

COVID-19 has exposed the inequities woven into the fabric of our society

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the long-standing health and financial inequities that exist for our communities of color as a result of systemic racism (see Figure VI). People of color, particularly Black and Indigenous people, throughout the country have contracted and died from the virus at disproportionate rates and they have been more likely to lose their jobs or income.

In New Mexico, lower income communities – which are disproportionately communities of color – have a higher prevalence of COVID-19 infections. On the left side of Figure VI you can see that census tracts with less than a 5% poverty rate have a COVID-19 prevalence of just over 200 for every 100,000 people. Now as you move to the right – the poverty rate grows – and the prevalence increases dramatically. The column on the far right shows that for census tracts with a poverty rate of 40% or more, the number of COVID-19 infections is ten times higher at more than 2,000 for every 100,000 New Mexicans.

These disparities among income levels exist due to the lack of options available to low-wage, often essential workers to deal with the virus. Many lack access to unemployment benefits, paid sick or family leave, and health insurance, and fewer work in occupations that can be done from home. In addition, long-standing, systemic failures in our tax and budget policies have equated to decades of divestment in New Mexicans earning low incomes. Together, these factors and this chronic divestment are the primary reasons people of color and those earning low incomes are more likely to have pre-existing health conditions, making them and their families more susceptible to the virus.

Those who are most at risk of contracting the virus in New Mexico are Native American communities due to the legacies of colonialism, racism, and the federal government’s failure to live up to its treaty obligations and adequately support the health and well-being of these communities. Comparing the proportion of COVID-19 infections to the proportion of New Mexico’s population illustrates how disproportionate the rates are: in the past couple of weeks, Native Americans accounted for 28% of infections – and in the spring it was even higher – while they compose only 10% of New Mexico’s population (Figure VII).

The opposite trend is true for white New Mexicans. They account for only 15% of infections despite being 37% of New Mexico’s population. And this is because occupations that are more likely to allow work from home – jobs that are also higher-paying – are disproportionately held by white workers.

Not only has the virus itself impacted lower income areas and communities of color more than wealthier, whiter communities, but so has the resulting recession, which is why it’s been deemed the most “unequal recession in modern history.” Workers earning low wages have been dealt the largest economic blow and many are still struggling to regain their employment, while those at or near the top of the economic ladder have largely been unaffected.[11] In New Mexico, employment rates among workers in the lowest wage level had fallen 14% by the end of September compared to the beginning of the year, while high-wage workers saw their employment return to pre-pandemic levels (Figure VIII).[12]

The workers most impacted by the recession also have less money in savings to help with the financial stress and uncertainty if they lose employment income, making these workers and their families more at risk for housing, food, and economic insecurity. In New Mexico, many families are having difficulty paying for typical household expenses like food, rent or mortgage, car payments, medical expenses, or student loans. In October, 35% of white adults – compared to 55% of Hispanic adults and 75% of Black adults – reported having this difficulty (Figure IX).

The blatant disparities in the health and economic consequences of this pandemic exist because of racism’s harmful legacy and ongoing damage for people of color, including Black and Indigenous people. Decades of policy and budget decisions by policymakers that benefited the wealthy and well-connected while severely limiting the funding available for public support programs, public health, and other community investments are what created the context behind why so many people across New Mexico and the country are now struggling to afford necessities for themselves and their families. By acknowledging this history as well as the impact of current policies, we can begin to advance antiracist policies that build more broadly shared prosperity.

New Mexico’s tax code is still a barrier to racial equity

New Mexico’s statutes do not mention race or ethnicity, but our tax system still impacts racial equity by outlining who pays their fair share of taxes, who doesn’t, and who benefits most from the way the system is structured. When looking at the combination of state and local taxes that New Mexicans pay, our state tax system is regressive and exacerbates income inequality. New Mexicans earning the lowest incomes pay 10% of their income in state and local taxes while the top income earners pay just over 6% of their income in these same taxes (see Figure X).

As shown in Figure XI, the share of white taxpayers in each income group increases as you move from the lowest income group on the left to the highest income group on the right. While white taxpayers file 45% of all tax returns, they file 63% of the returns in the top 1% income group. The reverse is true for taxpayers of color, who compose a disproportionately high share of taxpayers in the lowest income group. In the lowest 20% of income earners, taxpayers of color file 67% of returns, despite filing 55% of all returns.

Taken together it’s clear that the smaller share in income that the highest earning New Mexicans pay in state and local taxes more often benefits white taxpayers, while the higher share that the lowest earning New Mexicans pay harms taxpayers of color the most (Figure XII).

This upside-down tax system is the result of ineffective and unnecessary tax cuts to the wealthy and well-connected that have made our tax system grossly inequitable, starved our schools, health care systems, and other vital services of important funding, and dangerously increased our reliance on volatile oil and gas revenues. There has been no evidence that these tax cuts have done anything to benefit our economy as promised, either. Examples of poor tax policy decisions include:

“Big Mac” tax cuts

In 1981, property taxes were limited and personal income taxes were cut by 25%, then by another 33% in 1982. This is an example of how powerful interests, especially those representing extractive industries, have used their power to limit the revenue needed to support schools, local governments, and state government and shift the state to a higher reliance on the gross receipts tax.

More income tax cuts

In 2003, the top three personal income tax brackets were cut, benefiting only the highest-income earners in the state. This made our income tax system essentially flat. These cuts also included a 50% deduction for those with capital gains income – the money people make selling assets like stocks and real estate – which overwhelmingly benefited the very wealthiest New Mexicans.

Elimination of the estate tax

New Mexico used to have an estate tax – a tax on high-dollar property (like cash, real estate, or stocks) inherited from someone who has passed away – but due to federal tax changes in 2001 it was eliminated and never restored. The loss of the estate tax has reduced our ability to make public investments that foster economic growth while allowing wealth inequality to grow.

Corporate income tax cuts

In 2013, large corporations received a big and unnecessary tax cut, while New Mexicans were promised that it would attract new businesses – a promise that failed to materialize. We have lost important revenue that could have been invested in what actually benefits businesses, like an educated and skilled workforce, modern and robust infrastructure, and a market for their goods and services.

Special carve-outs from the gross receipts tax

Numerous carve-outs for the well-connected and big industry interests have resulted in a dwindling base for the gross receipts tax, which lawmakers have addressed by increasing the overall rate substantially. This harms families with low incomes the most because they pay a greater share of their income in gross receipts taxes. And because policymakers have chosen to cut taxes for the people and corporations who can most afford to pay them and not tax concentrated wealth, our state and local governments have had to rely more heavily on this regressive tax to fund community investments.

These failed fiscal policies have resulted in significantly less revenue, meaning less investment in progress and in our communities. As a consequence, our education systems cannot adequately prepare our children for success in a 21st century economy, higher education has been put out of reach for many families, and our health care systems are inadequate to meet the on-going needs of people during a pandemic. These shortfalls harm the people who are struggling the most to make ends meet, who are too often New Mexicans of color fighting against decades of discrimination. This is especially true for public education, where the Yazzie-Martinez lawsuit ruling in 2018 found that the state was failing to meet the educational needs of our students of color, as mandated by our constitution.

These tax policies were enacted because, for far too long, the discussions around tax cuts, deductions, credits, and rates were centered on improving conditions for the wealthy and well-connected. But in 2019, the conversation began to shift towards how tax policy can be utilized to improve the lives of families and children throughout our state.[13] Policymakers restored some progressivity to our tax code and introduced a new personal income tax bracket for the highest 3% of earners, increased a tax credit for working families earning low incomes, and scaled back a tax giveaway for wealthy New Mexicans. Together, these measures resulted in a tax cut for 70% of New Mexico’s families with children while raising some important revenue to invest in our communities and schools.[14]

We can build on this progress, create the opportunities needed for thriving and healthy communities, and ensure the wealthy and well-connected pay their fair share in taxes by enacting tax policies that are targeted toward improving racial and ethnic equity, while raising revenues for a sufficient budget.

Solutions for advancing equity through our tax code

Ensure the wealthy and well-connected pay their fair share

New Mexico’s wealthiest households have benefited most from our inequitable tax code, paying the smallest share of their income in state and local taxes to fund the foundations of our communities and economy. The pandemic has also exacerbated the massive wealth disparities that exist between communities of color and wealthy, white communities. The following changes to our tax code will help ensure that the wealthy and highest income earning residents, along with big, profitable corporations, pay their fair share in taxes.

Improve the fairness of our personal income tax

The best way to create a more equitable tax system is through the personal income tax because it is the only tax that is based on the ability to pay. Despite progress made in 2019, a family earning $25,000 per year is still paying the same marginal income tax rate as families earning $250,000 per year. We can continue to fix our upside-down tax code and ensure the wealthiest pay their fair share by introducing additional brackets at the high end of the income scale.

We can also require high-income earners to pay the top rate on all or most of their income, in what’s known as “tax benefit recapture.” New Mexico’s income tax code allows high-income earners to pay the top tax rate only on the portion of their income that falls in the highest tax bracket (called a standard graduated-rate income tax). This means, the lower tax rates that are intended to benefit low- and middle-income New Mexicans benefit the wealthy as well. Tax benefit recapture would require high-income earners to pay the top rate on all of their income.

Repeal the capital gains deduction

New Mexico is one of only nine states to tax income from capital gains (the profits from sales of assets such as stocks or real estate) at a lower rate than the wages of hard-working people are taxed. Currently, New Mexico allows 40% of this unearned income to be deducted from income taxes, even though there’s no evidence that it fosters investment and no requirement that the investments be made in New Mexico. It is an ineffective and unfair tax break that overwhelmingly benefits the wealthiest while taking revenue away from much-needed public investment. In fact, 88% of the value of this tax break goes to the highest 13% of income earners in New Mexico.[15] And when 87% of the wealth in this nation is held by white households, repealing the deduction would help narrow the yawning racial wealth divide in our state.[16]

Decouple from federal “Opportunity Zone” tax breaks

For the same reasons listed above, New Mexico should decouple from the federal “Opportunity Zone” (OZs) tax break. The 2017 federal tax bill created new capital gains tax breaks for investments in designated OZs. There is already considerable evidence that the program is merely a tax windfall for rich investors rather than for the intended beneficiaries of the policy: low-income residents in these identified zones. There’s also no requirement that New Mexican taxpayers who receive these tax breaks make these investments in our state. If New Mexico doesn’t disallow these breaks, we will continue to lose revenue to subsidize OZ investments in other states, when that revenue could be better spent investing in our communities[17]

Increase the corporate income tax

Businesses depend on a healthy state economy for their success and profitability, yet because of cuts to the corporate income tax in 2013, our state has had less revenue to invest in the programs and services that help create jobs and build a strong economy, like ensuring a healthy and educated workforce, improving public safety, and modernizing our infrastructure. Taxing corporations is an effective way to reduce the racial wealth gap as well, since taxes on corporate profits reduce the value of corporate stock, and white households are twice as likely to own stock as are Black and Hispanic households.[18] New Mexico should increase the corporate tax so big, profitable companies are paying their fair share for the use of New Mexico’s land and water, roads and bridges, and other public infrastructure and services.

Enact an estate or inheritance tax

A large share of the nation’s wealth is concentrated in the hands of very few, and taxes on inherited wealth – estate or inheritance taxes – can help build more broadly shared prosperity. An estate tax is a tax on property (like cash, real estate, or stocks) that’s levied before it is transferred to the heirs of someone who has passed away, while an inheritance tax is levied on the recipients rather than the estate itself. Most states, including New Mexico, used to have such taxes, but due to federal tax changes in 2001, only 17 states and D.C. now have an estate or inheritance tax.

Enact a “mansion tax” on high-value real estate

New Mexico can also adopt a tax on high-value housing, often called a mansion tax, to help fund crucial services. We can do this in one of two ways, either by levying a tax or fee at the time of sale (like a real estate transfer tax), or on an ongoing basis through existing property tax systems. No state has a graduated property tax rate for mansions, but seven states levy a surcharge on the highest-value homes or have a progressive bracket structure through their real estate transfer tax system.19]

Reform or repeal itemized deductions

Itemized deductions are costly and provide little-to-no benefit to most people earning low and middle incomes. The opportunity to reform itemized deductions is ripe because the 2017 federal income tax law – by significantly increasing the standard deduction – curtailed the number of taxpayers who itemize. Now it’s mostly affluent households that still itemize.[20] New Mexico should consider reforming the itemized deductions it allows – like home mortgage interest – to distribute existing asset-building tax subsidies more equitably.

Enact targeted policies and tax cuts for families most in need

One of the best ways to fix our upside-down tax system and help working families who are struggling financially is to enact targeted tax cuts. It’s a cost-effective and non-stigmatizing way to help families get by. What’s more, while the benefits – if any – of tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations are never worth as much as the tax cuts themselves cost, there is ample evidence that tax cuts for those earning the lowest incomes create economic activity, which results in more tax revenue. There are a number of well-researched ways to reduce taxes for working families and make our tax code more equitable, including:

Expand and increase the Working Families Tax Credit

Tax credits like the Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC) improve the health and well-being of the families and children who receive them. The WFTC – which is worth 17% of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit – benefits more than 200,000 New Mexican families, with top beneficiaries including essential workers and people of color – two groups who have been disproportionately harmed by COVID-19. The WFTC also improves physical and mental health by reducing financial hardship and giving families more money to spend on food and other household goods. It’s a common sense, bi-partisan solution to help New Mexico families survive through and thrive after the pandemic and should be both increased in amount and expanded to individuals who are currently excluded, like workers who file their taxes with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) and young, childless workers.[21]

Increase the Low-Income Comprehensive Tax Rebate

The Low-Income Comprehensive Tax Rebate (LICTR) is another tax policy tool to help improve equity and invest in our families. LICTR puts money back into the pockets of New Mexicans earning the lowest incomes, and rebates like LICTR are often spent quickly and locally on everyday goods and services like transportation and child care – keeping money flowing throughout our economy. Originally enacted to counter the regressive nature of the state’s gross receipts tax, the rebate amount has not been increased in over 20 years. Simply adjusting the rebate to account for inflation would bring some fairness back to our tax system and help families who are struggling financially to afford basic necessities.[22]

Enact a state Child Tax Credit

Enacting a child tax credit would improve economic equity for families of color and women and help address our high rate of child poverty. Improving family economic well-being is important because it is a critical foundation for healthy child development. Exposure to economic stress and hardship can take a toll on a child’s physical and mental health, educational achievement, and social-emotional well-being. Like the WFTC, a child tax credit is shown to improve infant and maternal health, reduce childhood poverty, improve test scores, and result in higher graduation and college attendance rates.[23] All of these benefits accrue to the larger community in the form of lower costs for programs to remediate the long-term effects of poverty as well as a stronger economy.

Create and protect an equitable budget and tax code

Communities of color have long been underfunded and under-resourced, adding to the many barriers they already face due to systemic racism. Our tax and budget policies must meet the needs of our families of color and ensure that they have the same access to opportunities that white families have enjoyed throughout history. Our revenues also need to be sustainable and adequate so we can build an equitable budget regardless of the state’s economy. Policymakers should:

Increase the Land Grant Permanent Fund distribution

New Mexico has the nation’s second largest Land Grant Permanent Fund (LGPF). Legislators and voters should choose to increase the distribution of the fund, which is currently only 5% of the 5-year average value of the corpus. Increasing the distribution by just one more percent would help us make the necessary investments in the early childhood education programs that will help our kids – 76% of whom are children of color – be better prepared when they start school, increase college attendance, and enter the workforce with the skills needed to succeed.

Evaluate how we spend through our tax code via exemptions and deductions

New Mexico gives away more than $1 billion a year in tax credits, exemptions and deductions to people and businesses throughout the state. This spending through the tax code is known as a tax expenditure. While some of these expenditures benefit families struggling financially to make ends meet – like the food tax deduction and a credit for working families – others are mere giveaways for special interests and big corporations. These hand-outs need to be evaluated regularly for effectiveness, and if they are not helping our economy or our people prosper, they should be repealed. Similarly, future proposals for exemptions, credits, or deductions need to also be evaluated for impacts on equity and intended purpose.

Keep TABOR-like policies and supermajority requirements out of our tax code

A so-called Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR) is a constitutional amendment that would severely limit the state’s ability to invest in our communities, as it would require a supermajority – a vote of 60% or more – of the state legislature to approve any tax increases.[24] Colorado is the only state to have enacted a TABOR and it is struggling to meet the needs of its residents, having to rely more and more on extremely regressive fees that fall most heavily on communities of color.[25]

Continue building up our state rainy day fund

Before the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing recession, New Mexico was ranked 4th in the nation in terms of having adequate reserves, and our rainy day fund certainly helped the state avoid larger cuts to the state budget.[26] During times of economic downturns, rainy day funds help maintain important public services that help families – particularly families of color – survive through these times of crises. Our lawmakers need to continue to build up adequate reserves and utilize them when they are needed instead of cutting critical programs and services that help families make ends meet.

Building a stronger, more equitable New Mexico

Every child in New Mexico deserves the opportunity to realize their full potential, yet too many hurdles exist for children and families of color that reduce their opportunities to truly thrive and prosper. These hurdles have been constructed, heightened, and shifted time and time again throughout our history, creating a legacy of racist and discriminatory policies and actions. Our tax and budget policies have also deepened racial inequities in New Mexico by giving handouts to the state’s wealthiest, mostly white, residents, expecting those earning the least to pay the highest share of their income in taxes, while starving our budget of the revenue needed to adequately invest in the most underserved communities and classrooms. But as we saw in 2019, tax policy can be a powerful tool to advance racial and ethnic equity. We must build on this progress by ensuring the wealthy, well-connected, and big corporations pay their fair share in taxes, enacting and expanding tax policies targeted to families most in need, and creating an equitable, antiracist tax code and protecting an adequate budget.

Making these important reforms will help us build a stronger New Mexico that values families and ensures all children have the opportunities they need to succeed; a stronger New Mexico that attracts new businesses with jobs that pay livable wages and important benefits like health insurance; and a stronger New Mexico where education is supported from before we’re born until we land a career. Together, we can create a stronger New Mexico by investing in the health, well-being, and potential of our people.

Endnotes

[1] “What’s really behind NM’s budget woes,” New Mexico Voices for Children (NM Voices), 2016

[2] “Advancing Racial Equity with State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), Nov. 2018

[3] Dorothy Overstreet Pratt, Sowing the Wind: The Mississippi Constitutional Convention of 1890, University Press of Mississippi, 2018, p. 130-131

[4] Malcolm Cook McMillan, Constitutional Development in Alabama, 1798-1901: A Study in Politics, the Negro, and Sectionalism, The Reprint Company, Spartanburg, South Carolina, 1978, p. 306

[5] Mississippi House Journal, 1932, p. 787, accessed through the University of Mississippi libraries

[6] “Power to Destroy: Discriminatory Property Assessments and the Struggle for Tax Justice in Mississippi,” The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 82, No. 3, Aug. 2016, p. 581

[7] “Examining the Black-white wealth gap,” Brookings Institute, Feb. 2020

[8] “Kept Out: For people of color, banks are shutting the door to homeownership,” Reveal, The Center for Investigative Reporting, Feb. 2018

[9] “What Drives Racial and Ethnic Differences in High Cost Mortgages? The Role of High Risk Lenders,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Feb. 2016

[10] Kijakazi, Kilolo, “Bold, Equitable Policy Solutions are Needed to Close the Racial and Gender Wealth Gaps,” statement before the Subcommittee on Diversity and Inclusion Financial Services Committee, United States House of Representatives, Sept. 24, 2019

[11] “The covid recession economically demolished minority and low income workers and barely touched the wealthy,” The Washington Post, Sept. 2020

[12] Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker, https://tracktherecovery.org/, accessed Nov. 10, 2020

[13] “Advancing Equity in New Mexico: Tax Policy,” NM Voices, May 2019

[14] “Fairer Taxes Put Us on the Road to a Stronger New Mexico!,” NM Voices, Oct. 2019

[15] IRS Statistics of Income, 2017

[16] “Wealthiest 10 Percent of White Households Own Two-Thirds of U.S. Wealth,” CBPP, 2016

[17] “States Should Decouple Their Income Taxes from Federal ‘Opportunity Zone’ Tax Breaks ASAP,” CBPP, April 2019

[18] Lisa J Dettling et. Al, “Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” Federal Reserve Board, Sept. 27, 2017

[19] “State ‘Mansion Taxes’ on Very Expensive Homes,” CBPP, Oct. 2019

[20] “State Itemized Deductions: Surveying the Landscape, Exploring Reforms,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Feb. 2020

[21] “The Working Families Tax Credit Will Help New Mexico Bounce Back,” NM Voices, Nov. 2020

[22] “New Mexico must step up to help our families who are struggling,” NM Voices, Nov. 2020

[23] “A new Child Tax Credit would put us on the road to a stronger New Mexico,” NM Voices, Feb. 2019

[24] Six Reasons Why Supermajority Requirements to Raise Taxes Are a Bad Idea, CBPP, Feb. 2020

[25] Policy Basics: Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR) CBPP, Nov. 2019

[26] Some States Much Better Prepared Than Others for Recession, CBPP, Mar. 2020