Produced in conjunction with the NM Center on Law and Poverty

Download this fact sheet (Mar. 2016; 4 pages; pdf)

Years out of compliance

For 25 years—since 1991—New Mexico’s Human Services Department (HSD) has been under federal court order to bring the basic processing of medical and food assistance benefits into compliance with federal law.

In just the past three years, the court has entered six orders directing HSD to comply with federal law. Violations included unlawful delays and denials of food and medical assistance to eligible New Mexicans.

In May of 2014, a federal judge found that tens of thousands of New Mexico families were improperly being denied food and medical assistance. HSD was ordered to clear their backlog of cases and to immediately begin complying with the processing standards required by federal law.

The problems were so severe that the court ordered HSD to cease closing or denying cases for “procedural reasons”—meaning for the failure to complete or turn in paperwork and attend an interview—because the Department was still not following procedural requirements.

In December 2015, the New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty reviewed a random sample of case files that the state sought to close due to the applicant or participant’s alleged failure to complete the application or renewal process.

Now, nearly two years later, the review results on the following pages show that HSD continues to violate federal law and the court’s order. Eligible families continue to face illegal delays and denial of benefits.

In a time of state revenue shortfalls, the Department is unnecessarily expending scarce resources on illegal and inefficient processing systems.

Inefficiencies waste money

When inefficient processing results in HSD delaying benefits to eligible families, forcing them to go back through the application process, this is called “churn.” Churn not only disrupts a family’s access to benefits—which can compromise a family’s health and a child’s education—it also creates an unnecessary increase in applications, which costs the state money that could be better spent elsewhere.

Processing an application costs the state double or triple the cost of processing a renewal.1

The Center on Law and Social Policy recently estimated that churn from the Philadelphia County Assistance Office alone costs Pennsylvania almost $9 million annually in needless administrative costs. In addition, the Pennsylvania economy loses out on an estimated $69 million each year due to SNAP benefits lapsing because of churn.2

The population of New Mexico is about 2 million people—larger than the population of Philadelphia County, at 1.56 million.3 Given New Mexico’s larger population, high levels of poverty, and undoubtedly high churn rates, we could be wasting even more money and losing even more economic activity.

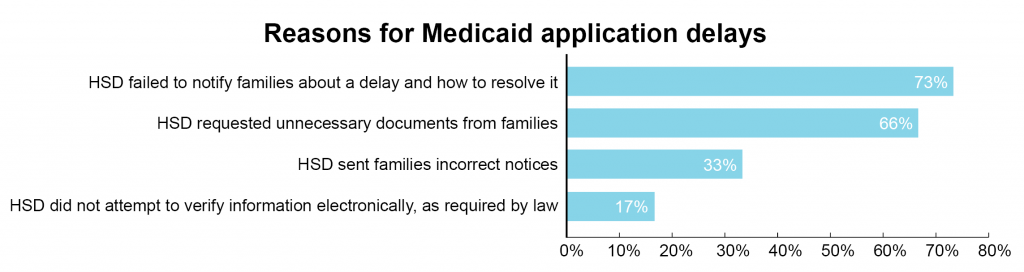

Delayed health care benefits

Case example:

A Hobbs family of four—including a 1-year-old child—was due to have their Medicaid renewed in March 2015. HSD made no attempts to renew the family’s Medicaid with available electronic information. HSD closed the 1-year-old’s Medicaid case in March, leaving the child without medical coverage, and left the rest of the family in a “pending status.” Four months later, in July, HSD sent the family a notice of delay saying that their Medicaid benefits could not be renewed because they had not returned the renewal form, despite the fact that HSD had never sent the renewal notice.

In the same month, the family was sent a notice telling them that they had to provide two months’ worth of paycheck stubs to prove their continued eligibility for Medicaid. One month’s worth of pay stubs is all that is required by law and it is only required if the family has changes in income. The family had reported no changes. After sitting in a pending status for seven months, the family’s case was finally reviewed again in October 2015—seven months later—and the family’s Medicaid coverage was renewed based on information already on file.

Case example:

A family of two living in Albuquerque applied for Medicaid in March 2015. On the application, the family indicated that they had no income. Rather than checking electronic sources of information to confirm that the family had no income, the Department requested proof from the household.

Notes in the family’s file say that the case could not be processed until the family provided sufficient proof that they had no income—despite the fact that the law prevents HSD from making families prove a negative statement. HSD never sent the family a notice explaining why they had not processed the case. As of December 2015—nine months later—the family was still waiting for Medicaid.

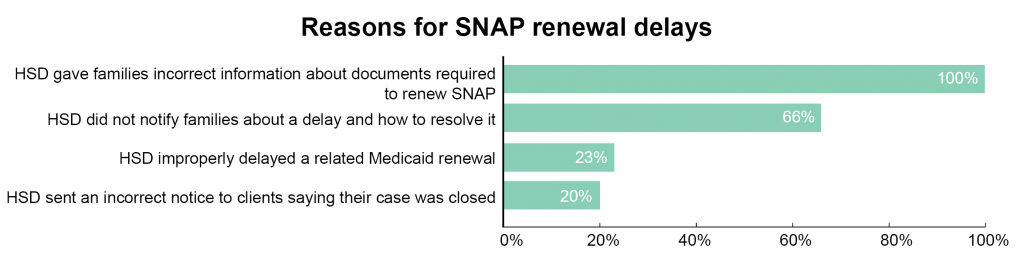

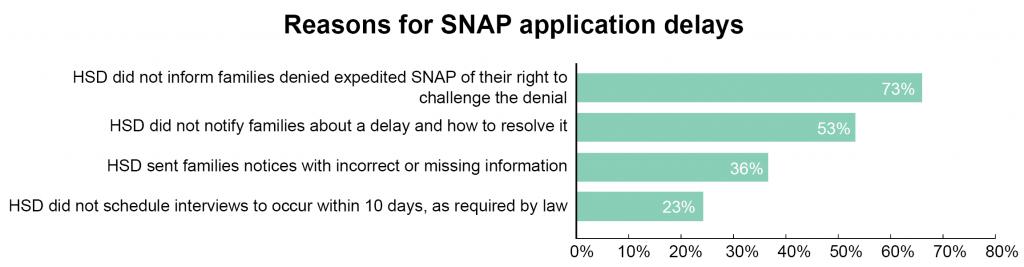

Delayed food assistance benefits

Case example:

In August 2015, an elderly man from Alamogordo who has no income was due to renew his food stamps. However, HSD failed to send him the required renewal form. When HSD improperly closed his case at the end of August, they also did not send him the legally required notice informing him that his food assistance case was being closed, so he had no idea that he would not receive food assistance in September as he was expecting.

Instead of sending the required renewal form and notice of case closure, HSD sent a notice stating that his food assistance was delayed because HSD was behind in processing his recertification paperwork. This notice was both confusing and incorrect because HSD never received any recertification paperwork from him. After going three weeks without food assistance, the man went to an Income Support Division office to submit a new application for food assistance.

Case example:

After experiencing a total loss of household income, an Albuquerque resident applied for food assistance in May 2015. He was eligible for emergency food assistance because he had no income or assets. However, his caseworker improperly denied him emergency food assistance and failed to inform him that he could contest this decision by meeting with a supervisor to explain his situation. Even though interviews must occur within 10 days of the application, his interview was scheduled for one month after he applied. After the month-long delay, he did not appear at the interview.

In June, HSD sent him a notice telling him that his case was delayed because HSD had not finished reviewing his file. This was incorrect. The case was pending because the interview had not taken place. Not knowing that he could simply schedule and complete an interview to finish his application, he ended up waiting for benefits through October of 2015—more than five months after the date of application.

Common-sense steps HSD can take to improve efficiency, save money, and resolve litigation

1. Eliminate requests for unnecessary documents

Federal law precludes states from requiring documents from applicants and participants that are not necessary to determine eligibility. New Mexico’s HSD continues to require documents that are either not necessary to determine eligibility or that the state already has access to through electronic interfaces. These unnecessary requests require significant additional work and often delay and deny critical assistance to eligible families.

2. Make client notices accurate and understandable

HSD reports that 35 percent of decisions to deny or close SNAP are done with incorrect notices.4 Families often receive notices that are confusing and that contain incorrect information about what the family must do to keep their benefits. This is despite the fact that HSD has been under court order to bring its notices into compliance with the law for over two decades. In 2013, the Department began using a new IT system that is capable of implementing the changes required by law, but the changes still have not been made.

3. Automate Medicaid renewals

State agencies must attempt to renew Medicaid for families based on information electronically available whenever possible. This is known as ex parte renewal. Data show that New Mexico does not attempt ex parte renewal before requesting documentation and the completion of forms from families.

Many states automate renewals to eliminate paperwork wherever possible. Medicaid for eligible families can be automatically renewed whenever a family renews or updates their case information to remain enrolled in SNAP, for example. The IT contractor that HSD uses has already programmed automated Medicaid renewals in other states.

4. Create a comprehensive, accurate online worker manual

New Mexico does not have a comprehensive manual for HSD workers to use in processing cases and determining eligibility. Instead, employees are directed to the New Mexico Administrative Code (NMAC) for policy guidance. Unfortunately, the NMAC is neither up-to-date nor easily understandable. In addition, large portions of the NMAC conflict with federal law. Policy memoranda issued by the state are put on a shared drive for workers to access. However, the memoranda are not indexed to the NMAC sections to which they apply. As a result, workers are often not aware of a relevant memo they should be following.

Many states invest in an online worker manual as an effective and up-to-date reference for workers. This helps workers process cases as required by law and in the most efficient manner possible.

5. Collect and share data on enrollment and processing

The strongest measure of the state’s efficiency in processing applications and renewals is the churn rate. Churn happens when eligible individuals lose benefits for a procedural reason—like the failure to turn in paperwork or attend an interview—only to reapply for the same benefits shortly thereafter. Churn creates an unnecessary increase in applications, which are more costly to process than renewals.

Measuring and reducing churn would position New Mexico to use its limited resources more efficiently to improve the timeliness and accuracy of eligibility determinations and demonstrate compliance with court orders.

Endnotes

1. “Understanding the Rates, Causes, and Costs of Churning in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” USDA, November 2014

2. “Churn Hurts Clients, DHS Caseloads, and Pennsylvania’s Economy,” Center on Law and Social Policy, January 2015

3. US Census QuickFacts, 2014

4. General Information Memorandum ISD-GI 16-22, HSD, March 1, 2016