Download this policy brief (Jan. 2016; 8 pages; pdf)

New Mexico is a poor state with high rates of food insecurity and with too many adults and children suffering from nutrition-related chronic conditions, including obesity and diabetes. Programs that incentivize consumption of locally grown, healthy, fresh produce to food-insecure individuals offer both health benefits to low-income communities as well as economic benefits to local farmers.

One example of a healthy food incentive program is Double Up Food Bucks (DUFB), which allows SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) recipients to double their purchases of fresh, locally grown produce when they shop at participating farmers’ markets. This helps qualifying households access more food at no extra cost and eat more locally grown, fresh fruits and vegetables while creating demand for such produce and circulating more money in the local economy. Programs like SNAP DUFB—that generate a win-win for vulnerable New Mexicans as well as local farmers—should continue to be supported and be expanded throughout New Mexico.

Low-income status and food insecurity

Low-income status and food insecurity

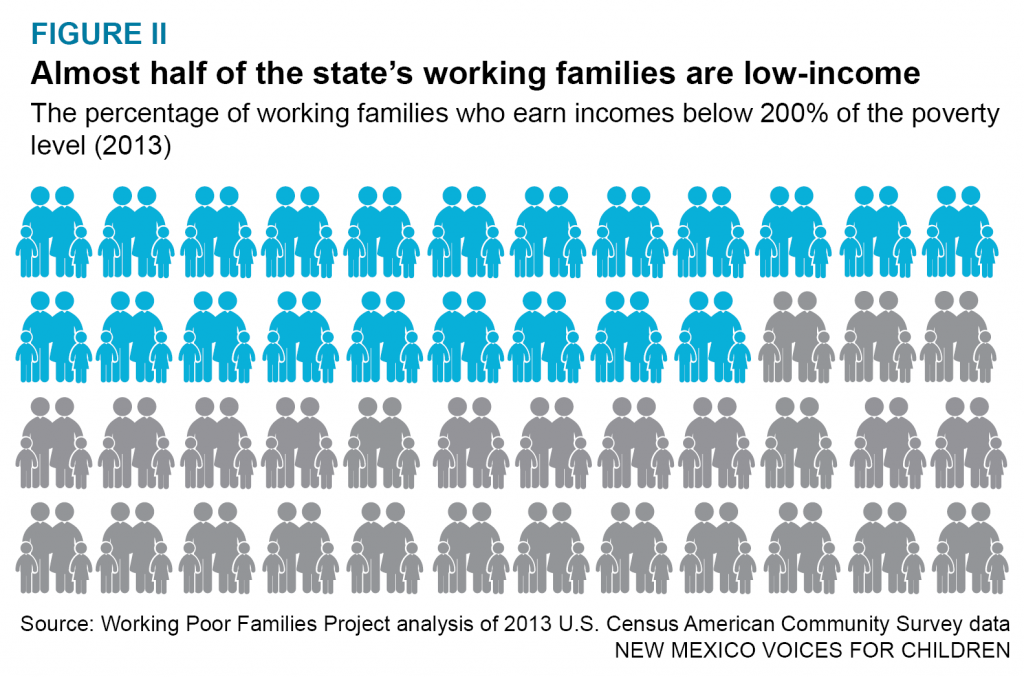

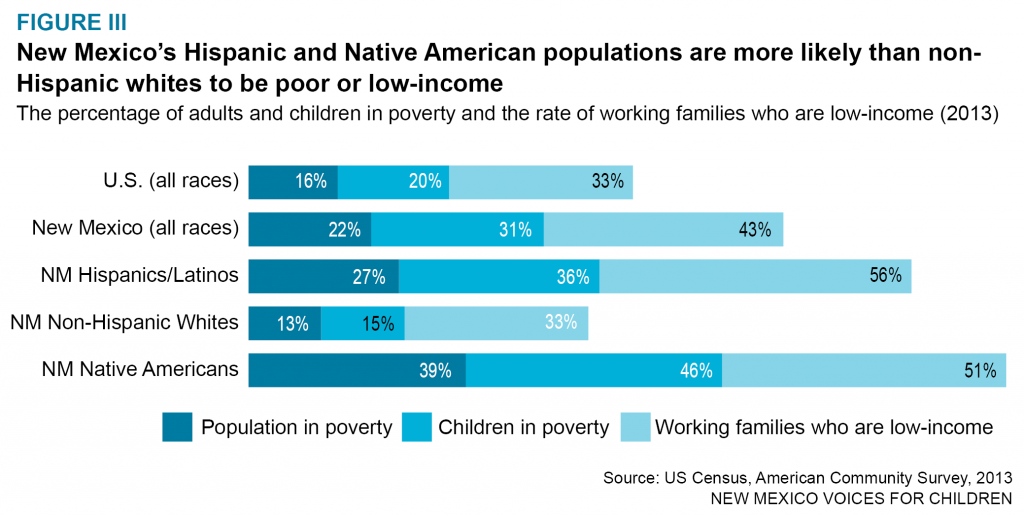

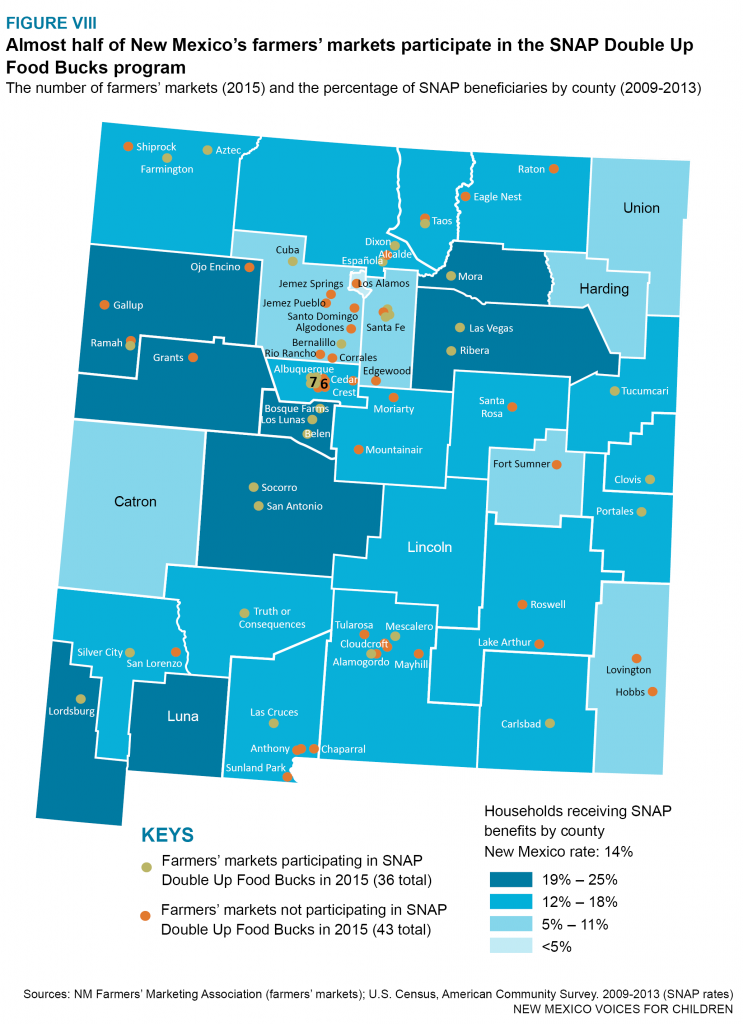

In New Mexico, 21 percent of the total population, and 30 percent of our children live at or below the federal poverty level—$19,790 for a family of three (see Figure I). This places New Mexico second highest in overall poverty and highest in child poverty nationwide.1 Many New Mexico families are working hard despite the slow statewide economic recovery but 42 percent of our working families are low-income, meaning they earn less than 200 percent of the poverty level2 (see Figure II). Racial and ethnic minorities are more likely than whites to live in poverty or earn low incomes (see Figure III).

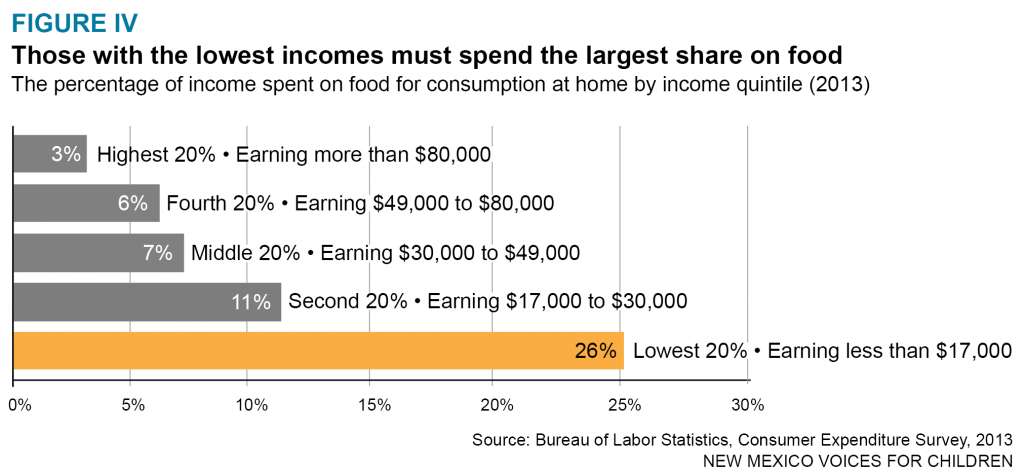

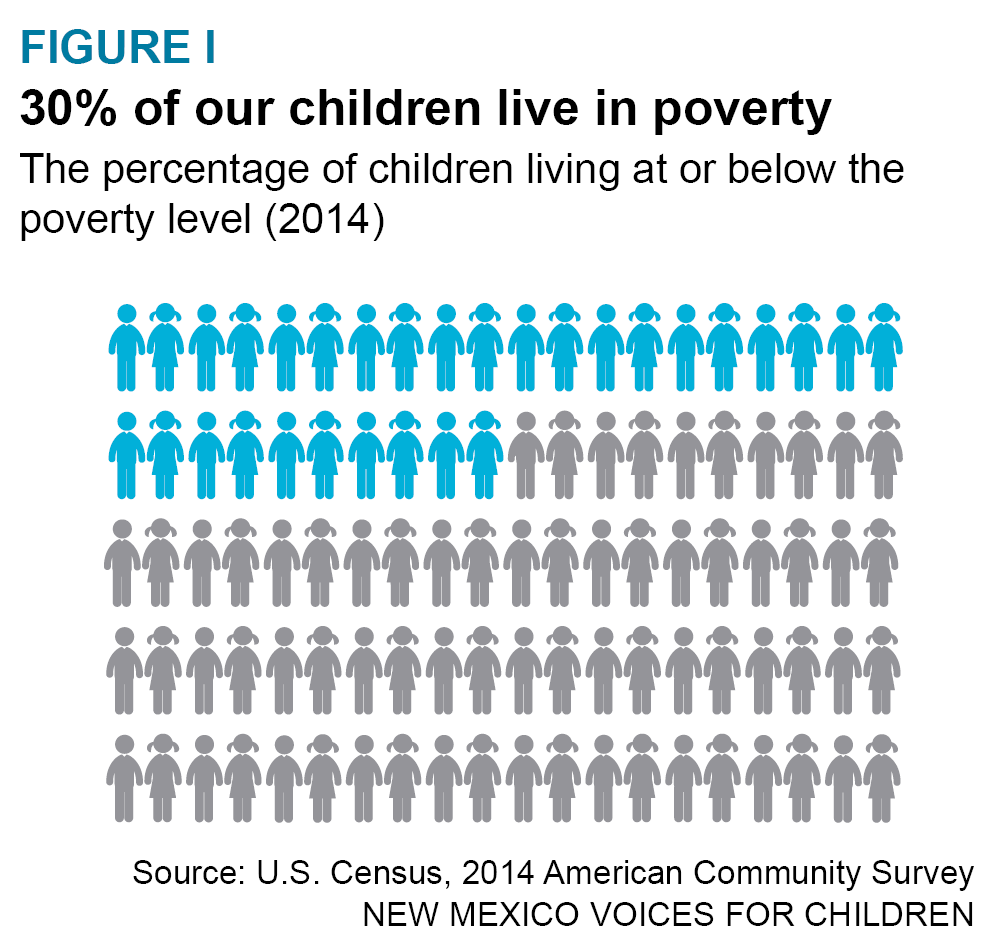

Low-income families are more likely to suffer from food insecurity3 and they have to spend a much larger portion of their income on food purchases than middle- or upper-income families. On average, the lowest 20 percent of households spends 26 percent of their income on food purchases, while the highest income earners spend only 3 percent (see Figure IV). Food insecurity affects 17 percent of New Mexico’s entire population and 28 percent of New Mexico’s children4 (see Figure V). New Mexico ranks eighth in the U.S. in overall food insecurity and third in child food insecurity.5 Of the more than 70,000 hungry New Mexicans who seek food assistance every week, between 30 and 40 percent are children and 21 percent are seniors over the age of 60.6

Food insecurity and poor nutrition

Food insecurity and poor nutrition

Eating healthy is expensive. A recent study showed that the cost of a healthy diet is $1.50 more per person per day than the cost of an unhealthy diet. While this seems small, it translates into big barriers for healthy eating when you consider that a family of four would have to pay an additional $2,200 per year on top of their existing grocery bills to provide a healthy diet.7 It is not surprising then that low-income families with tight food budgets often buy more processed foods because these foods are usually cheaper and have longer shelf lives than healthier, less processed foods.8 A survey done by the New Mexico Association of Food Banks found that 75 percent of food bank customers reported purchasing inexpensive, unhealthy food as the most common way to have at least some food at home to eat.9 Recently conducted focus groups with SNAP-eligible low-income community members in New Mexico found that this was indeed the situation for many of the participants. One community member from McKinley County shared that “I want to eat better, I want to be healthier, but I can’t afford it…” while another community member from Albuquerque mentioned that “(My son) gets a lot of not-great-for-him foods, just to make sure he’s getting enough to eat.”10

Poor nutrition and chronic health conditions

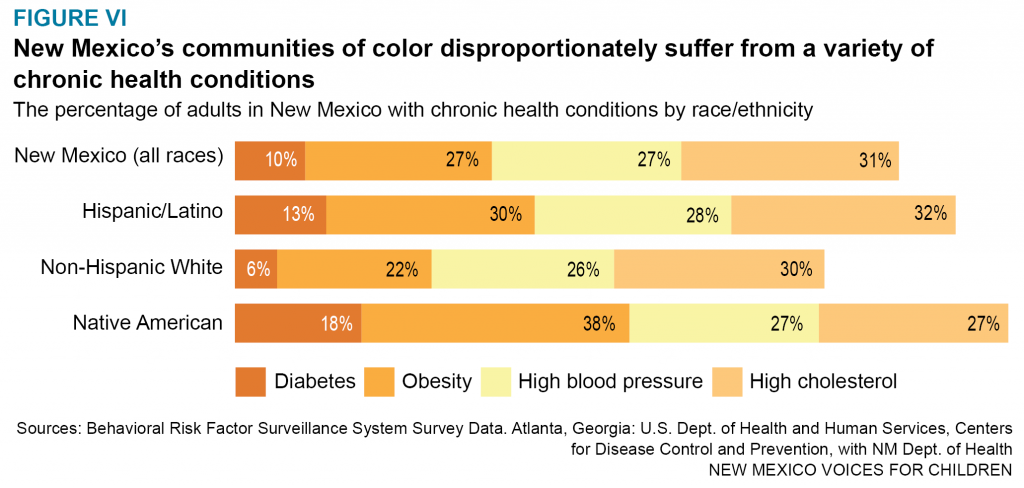

The strong link between food insecurity and obesity can be counter-intuitive but studies show that cost constraints often force low-income individuals to decrease their intake of more costly lean meats, dairy and fresh produce while increasing their intake of cheaper and more satiating foods containing processed grains and added sugar and fats.11 In addition to obesity, food-insecure individuals with poor nutrition are more likely to have chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular illnesses.12

Racial and ethnic minorities in New Mexico, who are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to be poor or low-income, are also more likely to suffer from a variety of nutrition-related chronic health conditions (see Figure VI). Economic and health statistics showcase the need for increased funding for programs like SNAP DUFB that help low-income individuals have access to healthier foods, particularly fresh produce.

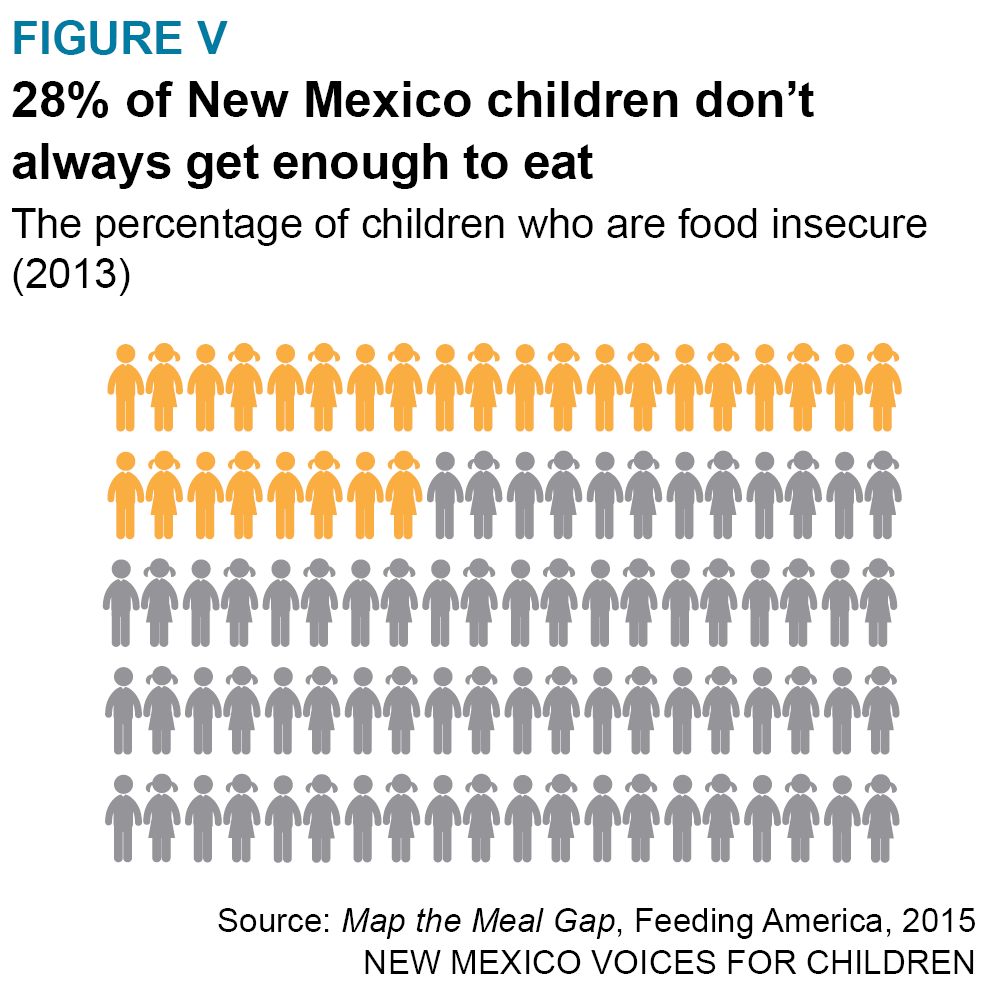

SNAP Double Up Food Bucks increases access to affordable fresh produce

In 2014, SNAP benefits helped partially cover food expenses for 431,000 very low-income New Mexicans (or 21 percent of the state’s population compared with 15 percent nationwide), with an average monthly benefit per person in New Mexico of $121.13 An estimated 88 percent of New Mexico SNAP households are poor (below 100 percent of the poverty line) and 45 percent are in deep poverty (below 50 percent of the poverty line). Additionally, the majority of SNAP beneficiaries (63 percent) in the state are children, or elderly or disabled adults (see Figure VII)—in other words, people with high nutrition needs.14 Unfortunately, the state is considering reinstating work rules that go beyond the requirements mandated by the federal government. These new rules would require individuals between 16 and 59 years of age, including parents with children older than 12, to work in order to access SNAP benefits. Those unable to find employment would be required to participate in many hours of volunteering or job training just to get the nutrition assistance.

Although the state is looking to reduce SNAP enrollment numbers, the Legislature in 2015 appropriated $400,000 for the SNAP DUFB program to enable SNAP recipients to match their SNAP benefits one-to-one at participating farmers’ markets across the state. Programs that promote the consumption of fresh produce are needed in New Mexico where only 18 percent of adults and 21 percent of children and teens eat the recommended five or more fruit and vegetable servings per day.15 Additionally, too many areas in New Mexico are considered food deserts without ready access to fresh, healthy, and affordable food.16 The state ranked ninth in the rate of difficulty accessing affordable fresh fruits and vegetables (2008-2010) in both households with children and in all households. Urban areas are also affected, with Albuquerque ranking fourth among 100 U.S. metro areas for the highest rate of difficulty accessing affordable fresh fruits and vegetables in households with children and 13th in all households.17

SNAP Double Up Food Bucks creates demand for locally grown produce

SNAP benefits not only improve food security but also directly added $630 million to the New Mexico economy in 2014.18 The economic multiplier is strong: The USDA estimates that every $5 spent in SNAP benefits generate $9 in local economic activity.19 With the SNAP DUFB program, more SNAP beneficiaries shop at farmers’ markets for healthy produce and more of the economic stimulus benefits local farmers and other New Mexico food producers. The New Mexico Farmers’ Marketing Association reports that 2015 sales significantly increased at most farmers’ markets that offered the program.20 SNAP sales at farmers’ markets went from $128,000 in 2014, when the DUFB program was locally funded in a handful of farmers’ markets, to more than $350,000 in 2015, when a combination of federal and state funds spurred the expansion of the DUFB program to 34 farmers’ markets and two farm stands in 20 counties across the state. This 175 percent increase in SNAP sales was welcomed by local farmers, many of whom say they plan to expand farming operations due to increased demand. Counties with high food insecurity or SNAP participation rates that received large boosts in SNAP sales in 2015 through the DUFB program included Socorro, San Miguel, San Juan, Sierra, Rio Arriba, and Taos.

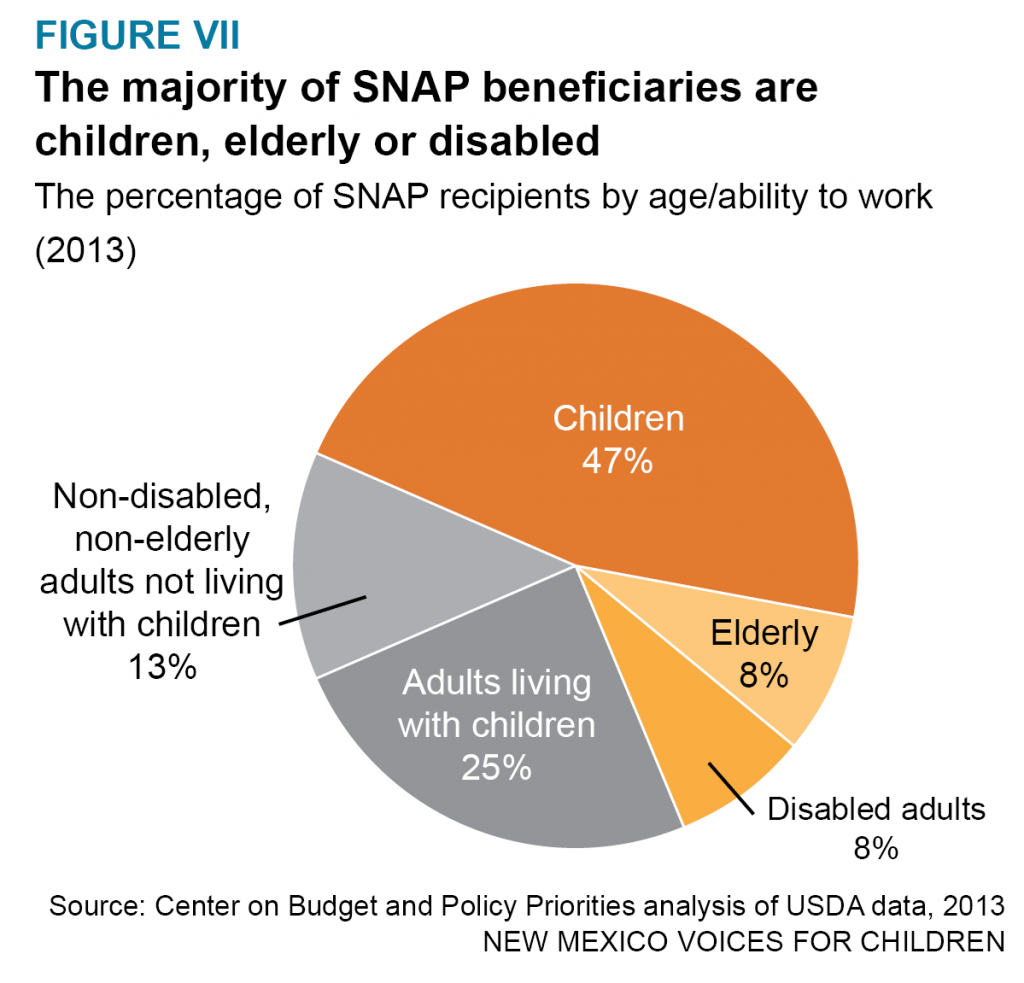

The New Mexico Farmers’ Marketing Association is currently compiling survey data for the New Mexico DUFB program but evaluations of similar SNAP voucher and coupon programs at farmers’ markets across the U.S. have shown that SNAP transactions usually double and can even quadruple.21 In surveys done in other states, 78 percent of vendors shared that they had more repeat customers because of the program and managers of farmers’ markets reported that DUFB programs brought in new and more diverse customers.22 Looking at SNAP recipient feedback, more than 75 percent shared that DUFB was a strong incentive to shop at farmers’ markets and that they increased their purchase of fruits and vegetables as a result.23 Almost half of New Mexico’s farmers’ markets are already participating in the DUFB program (see Figure VIII) but additional funding, support, and outreach could make this program truly statewide.

Policy recommendations

Support and expand SNAP DUFB. New Mexico’s farmers’ markets currently generate around $9 million in annual sales, according to the New Mexico Farmers’ Marketing Association. Those participating in DUFB in 2015 earned more than $350,000 in combined SNAP and SNAP DUFB sales. By 2016, more than half of all farmers’ markets will be participating in the DUFB program. Expanding the program to more farmers’ markets (including those in food insecure counties like Torrance, Lea and Chaves), to farm stands and co-op grocers will help increase access to healthy, nutritious foods for food-insecure New Mexicans while increasing demand for locally grown produce. Since SNAP DUFB state funding will likely leverage matching federal USDA funds, future recurring state funds should bring an additional $2 million in federal funds into the state during the next four years.

Increase participation in SNAP DUFB. Barriers to SNAP DUFB participation include insufficient access to information about the program; limited hours and locations of farmers’ markets; misconceptions around actual and perceived prices; inability to do bulk or one-stop shopping; unfamiliarity with how to prepare less-common produce; and limited marketing budgets that make it difficult to reach broad target audiences. Strategies for improving SNAP DUFB participation include: promoting the program directly to SNAP participants through the New Mexico Human Services Department; increasing training and outreach to statewide Income Support Division personnel who work directly with SNAP participants; increasing the administrative capacity of farmers’ markets staff and volunteers to run the program; conducting cultural competency training to increase the capacity of farmers’ market staff and volunteers to engage with, and better serve, diverse audiences; increasing the production and distribution of locally grown food to corner stores and other grocery stores so SNAP DUFB is available at more retail outlets; creating additional marketing materials (and translate into Spanish) that can be more widely disseminated in libraries, banks, post offices, DMV locations, child care sites, and schools; conducting more outreach via cooking demos on site and other community locations; leveraging SNAP-Ed funding to further crosslink nutritional education efforts; and working with health professionals to spread the word about the program.24

Support a variation of the Fruit and Vegetable Prescription (FVRx) program using SNAP DUFB funding. In FVRx programs, enrolled patients with nutrition-related illnesses receive nutritional counseling as well as “prescriptions” for no-cost fresh fruits and vegetables redeemable at participating farmers’ markets. A new pilot program created by the New Mexico Farmers’ Marketing Association called SNAP Rx will pair such a program at three federally qualified health clinics in Northern New Mexico with the existing funding and infrastructure of SNAP DUFB. This promising and innovative program should help foster partnerships between health care providers and low-income individuals dealing with diet-related illnesses while improving health outcomes of at-risk populations and further increasing the demand for locally grown fresh produce. Upon successful pilot implementation, the SNAP Rx program should be expanded across the state.

Increase funding for the New Mexico Grown Fresh Fruits and Vegetables for Schools Meals program. In 2015, with $364,300 of recurring state funding from the Legislature, more than 30 farms looking to expand their businesses participated in this program to provide locally grown fresh produce to as many as 218 School Food Authorities and school districts across the state, according to Farm to Table NM. For many food-insecure children, their school meals end up being their main meals of the day and providing nutritious foods that include locally grown fresh produce help improve children’s health while creating demand for locally grown produce. This funding also helps schools align with new federal school nutrition rules that now require twice as many servings of fresh fruits and vegetables in school meals.

Optimize and streamline SNAP enrollment. The state should take full advantage of federal SNAP offerings including: drawing down all available SNAP outreach dollars for increasing SNAP participation; continuing the federal exemptions from work requirements; eliminating excessive and administratively burdensome verification requirements; and implementing “express-lane” enrollment to link SNAP, Medicaid, and child care assistance. As mentioned earlier in the brief, every $5 spent in SNAP benefits generate $9 in local economic activity. This leads to a very positive economic multiplier effect for communities across New Mexico while increasing the food security and health outcomes of vulnerable children and adults in the state.

Endnotes

1 U.S. Census Bureau, 2014

2 Working Poor Families Project analysis of 2013 U.S. Census American Community Survey data

3 Hunger in America, 2014, Feeding America, 2014

4 Ibid

5 Map the Meal Gap, Feeding America, 2015 (2013 data)

6 Hunger in New Mexico, New Mexico Association of Food Banks

7 “Off the Cuff: The $1.50 Difference,” Harvard School of Public Health Magazine, 2014

8 “Poverty and Obesity: The role of energy density and energy costs,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2004; and “Obesity, diets, and social inequalities,” Nutrition Reviews, 2009

9 Missing Meals in New Mexico, NM Association of Food Banks, 2010

10 A Health Impact Assessment of a Food Tax in New Mexico, New Mexico Voices for Children, 2015

11 “A cost constraint alone has adverse effects on food selection and nutrient density: An analysis of human diets by linear programming,” The Journal of Nutrition, 2002

12 “Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: Results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2007; and “Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants,” The Journal of Nutrition, 2010

13 USDA SNAP state activity report, FY 2014

14 Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of data from USDA food and nutrition services, FY 2013

15 NM Youth Risk and Resiliency statewide survey, NM Department of Health, IBIS, 2007, 2009, 2011 compiled data

16 “Food Access Research Atlas Data File,” U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, August 2015

17 A Half Empty Plate: Fruit and Vegetable Affordability and Access Challenges in America, Food Research and Action Center (FRAC), 2011

18 NM SNAP Fact Sheet, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2015

19 The Food Assistance National Input-Output Multiplier Model and the Stimulus Effects of SNAP, 2010

20 NM Farmers’ Marketing Association 2015 report to the New Mexico Legislature

21 Double Value Coupon Program Diet and Shopping Behavior Study, Wholesome Wave, 2012

22 Double Up Food Bucks 2011 evaluation, Fair Food Network Project

23 SNAP Healthy Food Incentives Cluster Evaluation, 2013 Final Report, Community Science

24 Exploring Efforts to Increase Participation of SNAP Recipients at Farmers’ Markets, Emory University, 2015