How Systemic Inequities in Language Access are Impacting Asian, Pacific Islander, and African Immigrant and Refugee Communities During the Pandemic

By Derek Lin, MPH, Research and Policy Analyst, New Mexico Voices for Children and Judy Barnstone, Ph.D., Associate Professor, New Mexico Highlands University

Download this report (Aug. 2021; 18 pages; pdf)

Download the executive summary (Aug. 2021; 2 pages; pdf)

Link to the previous report Essential but Excluded: How COVID-19 Relief has Bypassed Immigrant Communities in New Mexico (April 2020)

Acknowledgements

New Mexico Voices for Children thanks NM Asian Family Center, NM Black Leadership Council, and United Voices for Newcomer Rights at the University of New Mexico for their integral role in designing and conducting this study. We would also like to thank the NM Center on Law and Poverty, Enlace Comunitario, El CENTRO de Igualdad y Derechos, Center for Civic Policy, and Somos un Pueblo Unido for contributions to this report. This report was funded, in part, by the Con Alma Health Foundation.

Introduction

Our communities are strongest when all New Mexicans can participate in our systems of government, which includes equitable access to public education, justice, the democratic process, and — for people who are under-resourced — assistance with food, health care, and housing. Currently, many New Mexicans who speak languages other than English, particularly those who were born in a foreign country, are excluded because of systemic inequities in language access. The inadequacy of our state’s multilingual interpretation and translation services causes significant hardship in many New Mexico communities because language access is critical for both good health and financial security.[1],[2] As we demonstrated in our previous report, Essential but Excluded: How COVID-19 Relief has Bypassed Immigrant Communities in New Mexico, despite their enormous economic and tax contributions, many immigrants were explicitly left out of federal pandemic relief. In this report, we would like to bring attention to additional groups of New Mexicans who may be eligible for relief but, due to inequities, have been unable to readily access it. Specifically, Asian and Pacific Islander (API) and African immigrants and refugees who speak languages other than English.

API and African immigrants and refugees have long faced inequities in language access in our state agencies. The ways in which these inequities create disproportionate hardship were made increasingly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, during which people who speak languages other than English faced language barriers that prevented them from utilizing emergency government assistance. Although the pandemic further exposed the state’s shortcomings in providing language access, these inequities are not new. As demonstrated by the Yazzie/Martinez v. The State of New Mexico lawsuit, there is a long history of discrimination against English-language learners in New Mexico’s public education system that has marginalized students who speak Spanish and Native American languages.[3],[4] Lack of language access is a barrier not only in education, but also to accessing social safety net services and equal justice under the law.[5],[6],[7] It even influences the extent to which many New Mexicans are able to participate in our democracy and make decisions that affect their families’ futures.[8] These realities were confirmed by what we found in the present study – that many people who are eligible for government services, public benefits, and other resources are excluded from them, in large part as a result of systemic inequities in language access.

In this study, New Mexico Voices for Children (NMVC) set out to document the stories of many of our state’s diverse immigrant and refugee community members, whose voices have been infrequently elevated in policy discussions. We focused on how these communities have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the systemic inequities at the root of disparities in health and economic well-being. While this study produced findings that go beyond what is discussed here, this report’s focus is on language access, which emerged as a dominant theme during our analysis of interview data. In addition to our findings on language access barriers that immigrants and refugees say they face in our state, we include a discussion of the critical work of caseworkers who help them overcome these barriers. The findings in this report should not only be viewed as documentation of the undue hardship faced during the pandemic by New Mexicans who speak languages other than English, but also as a call-to-action for state lawmakers to address the urgent need for equitable language access in New Mexico.

Study Design, Participants, and Analysis

In this mixed-method study, NMVC collaborated with immigrant- and refugee-serving partner organizations, namely UNM’s United Voices for Newcomer Rights (UVNR), New Mexico Asian Family Center (NMAFC), and the New Mexico Black Leadership Council (NMBLC), to conduct interviews with immigrant and refugee community members and their case workers. Each of these organizations serve their communities in different ways. One of UVNR’s roles is to provide social services and support, language interpretation, advocacy, and case management for refugees as they transition to life here in New Mexico. NMAFC provides culturally and linguistically appropriate services such as legal support, counseling services for victims of intimate partner violence, case management, and language interpretation for the API communities of New Mexico. Rather than providing direct services, NMBLC promotes leadership and youth development and civic engagement, among other programs.

Refugee: Someone who has been forced to flee their home because of war, violence or persecution.

Immigrant: Someone who makes a conscious decision to leave their home and move to a foreign country with the intention of settling there.

Interpretation: The conversion of words spoken in one language to those of another language during the course of a conversation, usually by a third party.

Translation: The conversion of words in one language to those in another language for use in written (printed, online, etc.) materials.

The intention of this study was to document the experiences of New Mexico’s diverse refugee and immigrant communities to better understand how the pandemic has affected them, and to use this information to inform equity-based policies for future advocacy efforts. Our previous Essential but Excluded study focused primarily on Spanish-speaking immigrants from Latin America. Therefore, in the present study we aimed to include a broader representation of immigrants and refugees, particularly those from countries in Asia and Africa.

The study used two methods: a closed-ended survey – meaning one in which participants were given a set number of responses from which they were to choose – which was administered to community members served by the three previously named agencies, and open-ended interviews, which were administered to both community members and their caseworkers at those agencies. Interviews and surveys for community members from NMAFC and NMRWP were performed in their preferred languages, whereas interviews with caseworkers were conducted in English. Community members from NMBLC were interviewed as part of an in-person focus group, conducted in English. In both cases, the same interview guide was used, and responses were recorded by the interviewers, in writing and/or on audio recordings.

The purpose of the survey was to learn more about the demographics of participants and also to assess quantitatively how their lives have been impacted. The purpose of the open-ended interview was to gain a more thorough understanding of the language access barriers faced by participants and how their circumstances have changed as a result of the pandemic, with questions focused on economic security, education access, physical and mental health, and child well-being. Our questions were used to identify what has and hasn’t been working during the pandemic and to document stories that captured individuals’ experiences as foreign-born New Mexicans. A total of 29 community members and six case workers participated in the study, all of whom were compensated for their time with $50 in cash.

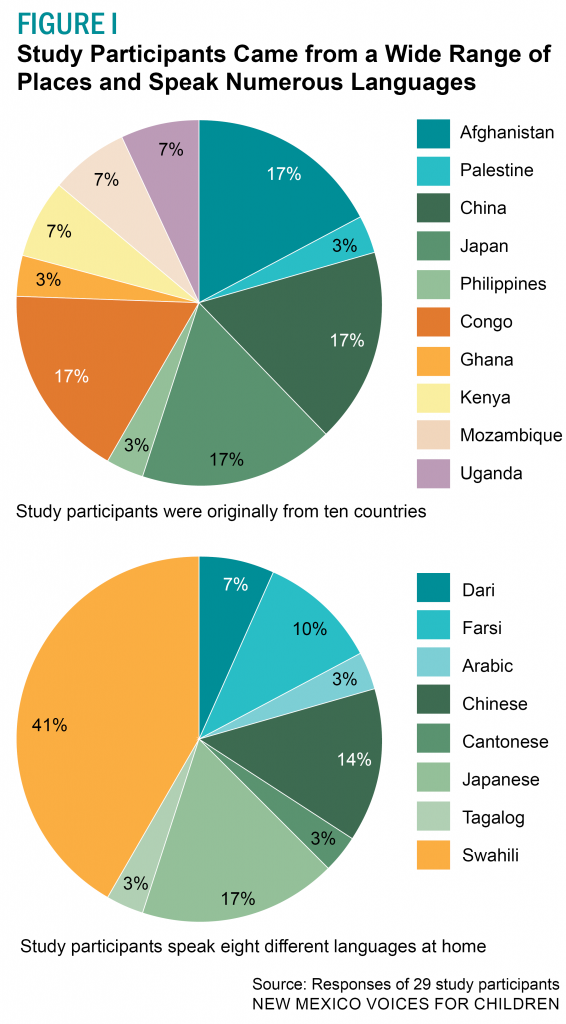

Of the 29 study participants, 27 were based in Albuquerque, and one participant each lived in Bernalillo and Rio Rancho. The participants were recruited by our partner organizations, which are also based in Albuquerque. Roughly 75% of participants identified as female and 25% identified as male. Household size varied among participants, ranging from one person to ten people in a household, with a median of four people per household. Among the participants, there was a median of two children per household with some households having no children and others having as many as five children. Community members who participated in the study immigrated from a total of ten different countries and speak eight different languages at home (see Figure I).

We chose to interview caseworkers because of their broad perspectives derived from serving a diverse client population. In addition to the countries of origin included in Figure I, the case workers we interviewed also serve clients from other countries in Asia and Africa, as well as the Middle East, including, but not limited to, Burundi, Rwanda, Somalia, Pakistan, India, Malaysia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, and Syria.

The interviews of community members were performed by caseworkers, and the interviews of caseworkers were performed by members of our partner organizations and other members of the NMVC research team. Due to the pandemic, interviews with community members and caseworkers from NMAFC and UVNR were conducted via video conference. Interviewer notes and transcriptions were closely reviewed, analyzed for themes, and then broadly categorized into three main domains: how participants’ lives have been directly impacted by the pandemic, including any unmet needs; what longstanding systems-level inequities create barriers for the participants; and the services and solutions community-based organizations provide to overcome those barriers.

It should be noted that this study is limited in scope due to NMVC’s selection of survey and interview questions geared specifically towards health and economic well-being. Additional limitations include a small sample size and a sample population that was exclusively composed of participants who were enrolled through community-based organizations at which the participants had sought casework services.

The Impact of the Pandemic

While we chose to categorize findings from the study into distinct themes – economic security, housing security, education, and health and health care – it should be noted that each of these categories is inextricably linked to the others. In every situation, the systemic lack of equitable language access makes it more difficult to secure living-wage employment, navigate the social safety net, seek necessary health care, and participate in remote education for both adults and children. These issues are further compounded by the stressors associated with acculturation and racism, a lack of familiarity with government systems, technology barriers, and a need for more culturally and linguistically appropriate activities for children and families.

Economic Security

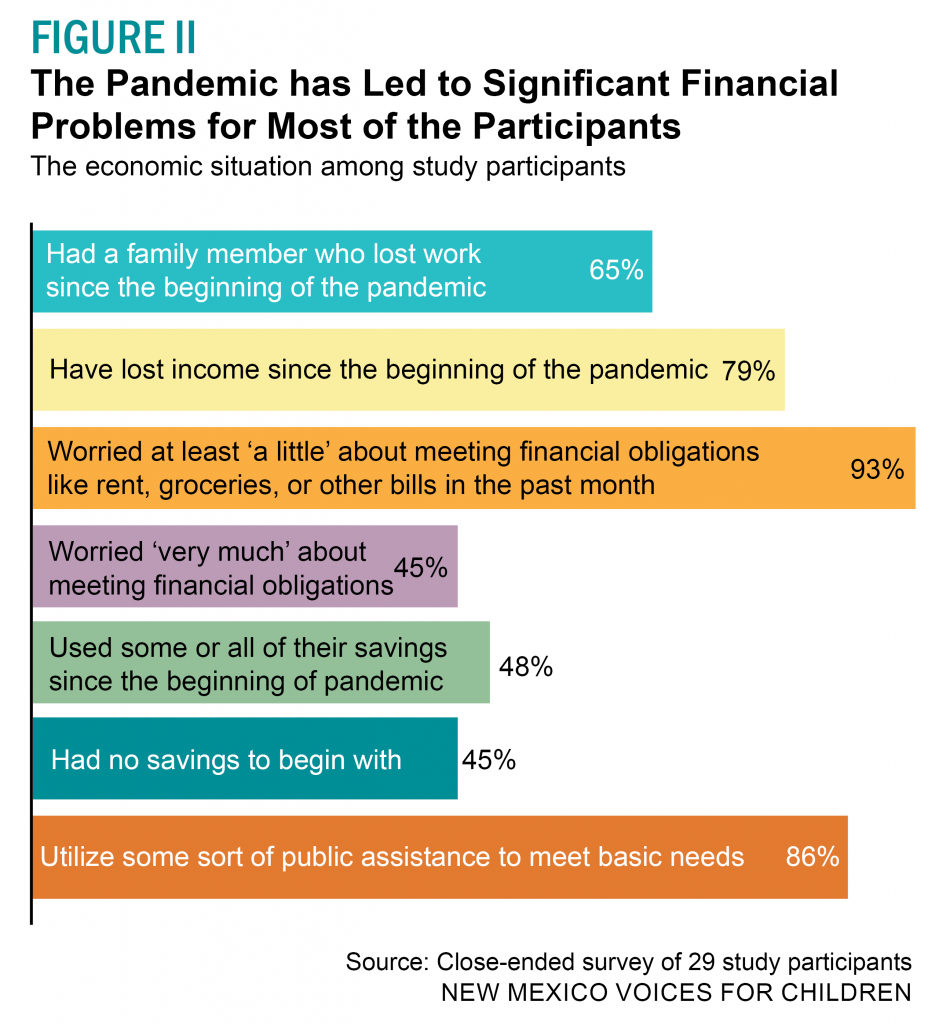

Many study participants expressed concern with meeting financial obligations (see Figure II). The majority of households had a family member who lost work since the beginning of the pandemic, and an even larger share of the participants’ households have lost income since the beginning of the pandemic. This is far higher than the 43% of all American households who reported having lost income during the pandemic.[9] These changes in income have had serious consequences for the economic security of the study participants, as almost all of them reported they worried at least ‘a little’ about meeting their financial obligations, like rent, groceries, or other bills in the past month, and nearly half reported they worried ‘very much.’

Everything is worrying me. I drained my savings, I haven’t received any stimulus, and I’m praying my tax return comes in soon because I don’t know what I’m going to do. I have relied on SNAP and rent assistance to make it.

”

-Japanese-speaking community member served by NMAFC

While two of the participants have not had to spend any of their savings since the beginning of the pandemic, about half of the participants had to use some or all of their savings and the rest did not have any savings to begin with. Many of the study participants reported significant economic hardship due to job loss and limited job opportunities. Many of these respondents reported working in relatively low-wage jobs in high-contact occupations, such as food service and health care, which were deemed essential but put workers at high risk of contracting COVID. Many worked in industries, such as hospitality, that put them at a higher risk of losing wages due to closures. A caseworker at NMAFC said, “They are having hard time obtaining jobs with [the] language barrier, and this pandemic made it worse. Most of the clients work for service industries such as restaurants, nail salons, and massage shops, and many of them were laid off.” The service and hospitality industries were hit the hardest by the economic recession caused by the pandemic.[10] Since immigrants and refugees of color commonly hold jobs in these sectors, these communities experienced disproportionate loss of income as a result of the pandemic.[11]

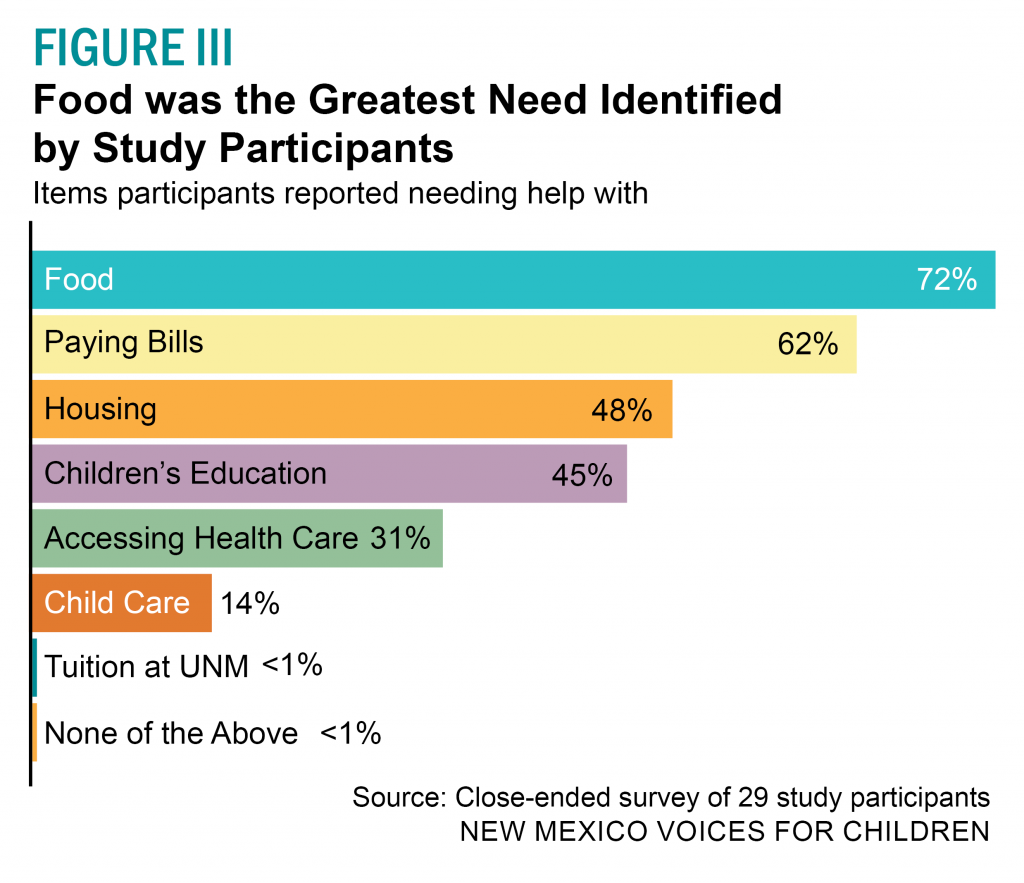

While the participants reported needing assistance from their caseworkers in all aspects of their lives (see Figure III), the most commonly identified need was food. Many immigrants, even those with documentation, are ineligible for government assistance for five years upon arriving, but that rule does not apply to refugees and asylees. The majority of participants, 86%, indicated they utilize some sort of public assistance to meet their basic needs, including Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Section 8 housing, and Unemployment Insurance (UI). These rates of public assistance utilization are much higher than are usage rates in the general public. These high rates reflect, in part, our selection of participants who are relatively recent arrivals to the US and have sought support from organizations that provide caseworker assistance.

Although many of the community members interviewed sought government assistance, they also reported that language barriers prevented them from readily accessing it. One Chinese-speaking community member said through a translator, “No one is working in my household at the moment … my English is poor, and I could not apply for anything myself until I received help from my NMAFC case manager.” Several participants talked about needing help from their caseworkers. One caseworker at UVNR described how her caseload has increased since the pandemic: “I’ve been helping with some new families, too, because of the pandemic. Most of them have lost their jobs, or they need help with rent assistance or unemployment.” Another caseworker said, “a lot of people are having problems getting their unemployment [benefits]. The Department of Workforce Solutions does not take non-proficient English as an excuse for why the clients did not apply for unemployment right away when they lost their job.”

One family, they had this issue. They couldn’t pay their utility electric bill, and they didn’t know about the system, and there was a language barrier, and they couldn’t pay the bill for two months, and after that, someone came and turned off their meter… But they couldn’t understand what she was doing… And for ten days they had no electricity, and they didn’t know where to go, who to reach out to, how to get the help.

”

-Caseworker at UVNR

Another barrier to applying for assistance is unfamiliarity with the various programs and systems. For New Mexicans who need to file for UI, for example, navigating the system to receive benefits can be complicated and challenging, particularly for people who are not familiar with it, even when they are English-proficient. “When working with NMAFC they have helped me apply for assistance and aid. They have been helpful in navigating the government agencies,” said a Japanese-speaking participant through a translator. Knowledge of the system is needed beyond the application process, as most programs have regular recertification requirements. Missing the weekly certification, or filling it out incorrectly, has resulted in some clients at UVNR being disenrolled from their benefits. One caseworker reported having as many as six regular clients who need weekly support in filling out their UI certificates. But the burden of filling out the weekly certificates also falls on children in the family: “If families have older kids, high school kids, I will teach the kids to help their family complete the weekly certificate,” the caseworker said. While this becomes a necessary strategy to help families become self-sufficient, thereby freeing up caseworkers to help others, it ends up placing an inordinate amount of responsibility on children for maintaining this critical cash assistance.

Several of the caseworkers mentioned that language barriers were further compounded by technology barriers – primarily access to a computer and an understanding of how to use it. According to one caseworker at UVNR: “The problem with the UI is the weekly certificate. People who do not speak English very well, who do not know how to use the computer to complete the certificate, they suffered a lot.” For one Arabic-speaking participant, language and technology barriers made it impossible to navigate the Human Services Department website and enroll in SNAP benefits without the help of a caseworker: “I don’t know what I would do if the NMAFC wasn’t there to help me,” they said through a translator. The correlation between language and technology barriers aligns with a finding at the national level showing that 21% of immigrants who speak a language other than English have no experience with computers, compared to 5% of English speakers.[12]

State agencies are required by federal law to provide meaningful access for people who speak languages other than English, however, their failure to do so creates barriers for many families in accessing and maintaining needed safety net benefits. While the Department of Workforce Solutions has a written plan for providing meaningful access and is currently in the process of translating vital documents into Vietnamese, the Human Services Department, Department of Health, Children, Youth, and Families Department, and Motor Vehicle Department do not provide multilingual translation and interpretation services, nor do they have any written plans to do so, according to public records requests by the New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty.[13] The result of this inequitable system is increased difficulty for some families in breaking the cycle of economic hardship. Although community-based organizations often help their clients overcome these inequities by filling in the gaps in services not provided by state agencies, the need for support is too great and the resources too few for these organizations to bridge the many gaps in government services.

Housing Security

Since housing is deeply intertwined with economic well-being, housing insecurity was also a significant issue for many of the study participants. One caseworker at UVNR reported that some of her clients “are still trying to find a job and employment, so, again, they need help with housing. This is a very big issue for them, paying their rent and utilities.” A combination of lost wages and unforeseen expenses forced some participants to dip into their savings or seek out emergency assistance, either from state agencies or through community-based organizations. Several participants mentioned receiving one-time assistance from NMAFC, which was a critical support that helped them keep their housing. While this option was sufficient for some study participants, others had to make the difficult decision to give up their housing, as one Arabic-speaking community member explained: “I lost my job, and I was struggling to pay rent and pay for my food. I had to give up my apartment and I moved in with a friend.” The merging of households, along with working and attending school from home, created overcrowded housing conditions for many participants. This overcrowding negatively impacted both parents’ employment and children’s education, creating stressful environments and contributing to poor mental health. According to one Japanese-speaking community member at NMAFC: “Adjusting to be working at home has been difficult, given my child is taking her classes on the other side of my small apartment. It has been difficult for me to focus on work tasks.”

Since COVID started, I have been teaching the classes online. To do so, I needed to purchase a faster computer, faster internet, and materials to teach online. The hours have been reduced, but the stuff I need to teach online was not provided and I had to use my savings… when I had to purchase the new computer and faster internet, it was very difficult to pay my rent. I applied for NMAFC one-time emergency assistance.

”

-Japanese-speaking community member served by NMAFC

The issue of overcrowded housing conditions is a longstanding problem for many of the study participants, particularly among refugees. In the interviews conducted by NMBLC with African refugees, participants reported that housing situations are often precarious, in that large and multigenerational families often live in small, substandard dwellings. Many refugees in Albuquerque depend on organizations such as UVNR and Lutheran Family Services for support in finding affordable housing. However, many of the study participants reported that the available housing options are often of poor quality or poorly maintained and too small for their families. According to an interview of a caseworker at UVNR: “Imagine ten people living in a three-bedroom apartment … it is hard to keep it clean, especially with all the food around. This can be a serious problem, especially with cockroaches. This is what happened to that family who got evicted, but we were able to advocate for them to slow the eviction process. UVNR, [Lutheran Family Services] and [Western Sky Community Care Medicaid] had to come together and reach out to the landlord and stop the eviction and negotiate to have extra time for them to find a new place and move out.” This story highlights the importance of community-based organizations as advocates for members of the refugee community, particularly those who speak languages other than English and are unfamiliar with the rental process.

Even when interpreters are available for people who speak languages other than English, problems can still arise when the contracts they sign are not in their preferred language. As one caseworker describes during an interview: “When refugees sign the contract, they had interpreters to help them sign, but interpreters did not go through the whole contract and interpret it word by word, so refugees sign but they do not fully understand all the terms in the contract,” which can result in them not fulfilling the terms of the contract (for example, not supplying pest control) and thereby place their housing security at risk. Incidents such as these are common, and thus achieving equitable language access includes providing people not only with interpreters for live conversations but also with translation of documents and other materials into their primary language.

It has been hard for schools to provide laptops to children who cannot afford them. It also seems hard to keep children engaged in education without the classroom. I have noticed some children thriving, and others not. There is never a middle ground in that regard. We really need to get kids back to school for their education, socialization, and overall mental health.

”

-Caseworker at NMAFC

Education

The transition to remote education presented numerous challenges for the study participants. For many of them, economic and housing insecurity, combined with an unfamiliarity with the school system and technology, negatively impacted their children’s education. One of the caseworkers at UVNR explained how these issues intersect for many of their clients: “some of [the clients] are still trying to find a job and employment, so … they need help with housing. This is a very big issue for them, paying their rent and utilities. They are still struggling. Some of the families, they have … children, like in high school, and they just … discontinued their education … to find a job and help their parents financially.” The cost of high-speed internet emerged as another common economic barrier impacting education. According to one Tagalog-speaking community member at NMAFC: “I cannot afford the faster internet for five children to use for schoolwork at once.” Some of our study participants did not have the capacity to homeschool their children while also maintaining their own employment, particularly those who could not work remotely.

Not knowing how to contact teachers was another issue further compounded by language and cultural barriers. A caseworker at UVNR described this common situation among their refugee clients: “[The children] had a hard time logging in classes and contacting their teachers. And in most cases, parents help them. But, like I said, the parents don’t know English, and they didn’t know about online classes, and they didn’t know about the system.” The result for many of the participants’ children was learning loss, and several participants had children who dropped out of school, including one Farsi- and Dari-speaking participant who told their interviewer: “My younger kids are doing online school, but my older kid dropped out because he was having a hard time.”

”

-Caseworker at UVNR

Difficulty navigating the public education system due to a lack of language access and other supports from school officials is documented as a longstanding issue for foreign-born parents even before the pandemic.[14] This is illustrated in a story from one of the parents served by NMAFC: “My oldest daughter was attending UNM last fall. She could not register this spring because they told her that she owed too much tuition [even] after applying [for] the student Pell Grant. After some research, they found out she was registered as an out-state student last fall. The daughter’s English was not proficient, but [she] did not receive any help from the high school since the school office had been closed. [She] is a bit depressed about not being able to register for class this spring.” Collectively, these inequities result in a lower quality of education for children of parents who speak languages other than English, which can have serious consequences for child development and future earning potential.

Doing online school is very difficult for my kids. My kids used to all [make] A+ grades but now their grades are not as great as before. In fact, my second kid is failing in some of his subjects.

”

-Community member served by NMAFC

We also found in the interview data that some participants who were pursuing post-secondary courses that would help them develop professionally or improve their English, were unable to continue due to the pandemic. A Swahili-speaking refugee reported in the focus group held by NMBLC that they had to postpone their education because of the high cost: “I am not going to school now. They say I owe $5,000 and I can’t pay it. I have to work.” For those adults who did enroll in educational coursework, economic stressors, which were compounded by language and cultural barriers, also made it difficult for them to engage in their courses: “I am enrolled in school right now. Sometimes it’s hard to concentrate, and not having a job has put a lot of stress on me. But I’m trying to finish school to better my future.” These interruptions make it harder for immigrants and refugees to establish themselves in New Mexico, advance professionally, and attain employment that pays living wages.

People are sad, anxious, scared, depressed, and feel isolated from their lives and community. Many people miss eating together as families, planning vacations, and seeing friends.

”

-Caseworker at NMAFC

Health and Health Care

Mental Health and Access to Care

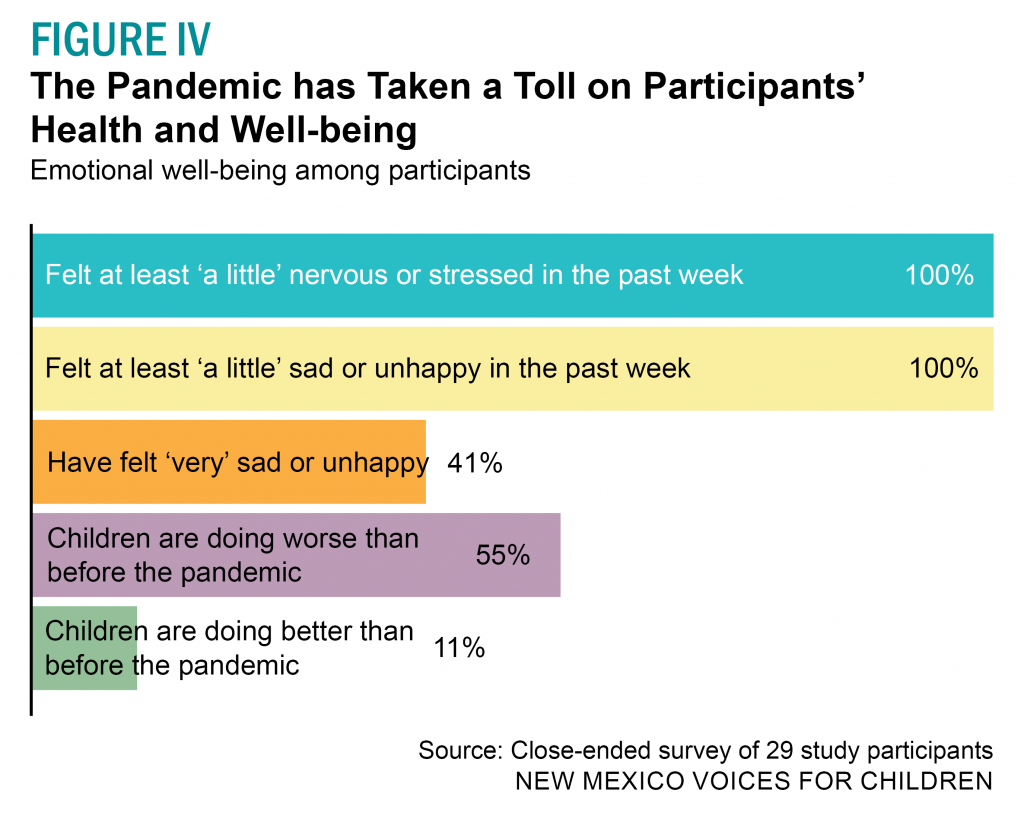

Mental health emerged as one of the most common health concerns for study participants. While the stressors of living through the pandemic had severe consequences for many New Mexicans, immigrants and refugees already struggling with acculturation to a new country experienced extra layers of stress, isolation, and depression. As shown in Figure IV, study participants had high rates of experiencing mental health problems such as nervousness, stress, sadness, and unhappiness. Feelings of isolation as an immigrant or refugee in a new country were worsened by the pandemic, as explained by a Japanese-speaking participant: “I meet friends a lot less. Being single with no family in town, I miss connecting with others so much. At times I feel awfully disconnected with the rest of the world and feel lonely.” For some refugees, leaving behind family and friends in an unsafe situation in their home country is a significant source of stress, as explained by a case worker at UVNR: “They are in a new place, a totally strange place, and their families are back in [their] country, and they are worried for them. They always hear news, bad news, about their country and its security situation. And they are worried for their close family members back there. And that makes it worse for them.”

Community-based organizations improve overall mental health and feelings of isolation by creating spaces for people to connect with other members of their communities. Participants spoke highly of the events at NMAFC, in particular, which hosts English support groups, peer support groups, yoga classes, and a resting circle for community members. Participants valued these recreational activities and expressed that they would like more culturally and linguistically appropriate opportunities for their families and children as well. In interviews, caseworkers across all three organizations expressed the need for more culturally and linguistically appropriate recreational activities as a way to connect people from similar backgrounds and build community, which is important for the mental health and well-being of their clients. Recreational activities conducted exclusively in English are inaccessible for many people who speak languages other than English, which perpetuates feelings of isolation.

I want to recognize and appreciate my community for being very kind. We love to share the resources that we learn with each other. I want to appreciate [my caseworker] for sharing her help and support for the community. My mom is going to join the peer support group and I am happy for her to spend some quality time with other women and learn from them.

”

-Dari-speaking community member served by NMAFC

Although the social isolation and increased stress caused by the pandemic created a higher demand for mental and behavioral health services, there has long been a critical shortage of providers who can offer culturally and linguistically appropriate services to members of these communities. Caseworkers report that there is a 4-month waiting list to see a mental health provider at NMAFC, resulting in unmet mental health needs for many API immigrant and refugee community members who speak a language other than English: “We need more therapists for our community. Currently, we have clients on a huge waiting list, and telling them we offer them therapy, them agreeing and then telling them they need to wait for four months is a huge letdown.” Not only does this allow conditions to go untreated – leading to worse physical and mental health outcomes – it erodes faith in the health care system, which can prevent people from seeking treatment in the future. Some community members experienced symptoms such as headaches or back pain that developed as a result of stress from the pandemic, but because of language and cultural barriers, they did not receive effective treatment from their providers.

All my follow up appointment were moved to online. Getting the right interpreter was difficult. A lot of misunderstandings was affecting my meetings with my doctors. Sometimes I had to use my daughter to help me with interpretations. I know it is not right to use my children for mental appointment, but I had no choice.

”

-Dari-speaking community member served by NMAFC

Like many issues faced by study participants, the shortage of culturally and linguistically appropriate physical and mental health care providers is compounded by additional barriers, such as unfamiliarity with the health system, and difficulty in navigating the telehealth system and in finding interpreters. Even those who were able to make appointment with providers, but were not proficient with smart phones and computers, found it more difficult to communicate effectively with their mental health care providers. Collectively, not being able to attend appointments in person resulted in additional misunderstandings between patients and their providers and delays in care.

One study participant reported having to use their child as an interpreter for their mental health appointments. Even though health care professionals are prohibited from using minors to interpret for their parents, it is a common practice when interpreters are not readily available.[15] Having children responsible for accurately translating medical information is dangerous due to the risk of serious health consequences. In some cases, it is the caseworkers who are providing interpretation during medical appointments. A UVNR caseworker shared the story of a client experiencing severe tension headaches. She reported that the community member was “not sure where to go. So I asked her if she needs any psychologist or psychiatrist, and if she wants, I can make an appointment, to which she said, ‘that will be good if that helped me. But you, you should be there to interpret for me, so I understand what the doctor says, and so the doctor understands what I’m saying.’ So I said, ‘okay that’s fine, I will do that.’” It is worth mentioning, however, that medical facilities do have some language services available, as explained by one Chinese-speaking participant who had to go to the hospital: “The medical staff used a phone interpreter, so I had no problem getting the medical help I needed.”

In addition to providing language interpretation, community-based organizations play a critical role in helping their clients navigate the process of applying for free or subsidized health care through programs like Medicaid and UNM Care. As one Chinese-speaking community member reported: “I had fibroids in my uterus that was causing me to bleed a lot during my period and lots of pain. I was not able to get treated. My case manager helped me get UNM Care. I was able to get the medical care I needed. They scheduled a surgery for me and removed the fibroid a couple of weeks ago. I am feeling much better.”

Child Mental Health and Well-being

When it came to the overall well-being of children in the home, there was some variation in how parents reported their children were doing, as shown in Figure IV. The mental health of some participants’ children has suffered as a result of not being in the classroom. One Swahili-speaking participant reported that: “the isolation for my kids has been really bad. They need to go to school.” During an interview of a caseworker at UVNR, the lack of recreational opportunities also came up as a significant contributor to the difficulties that some children faced during the pandemic: “[the kids] do not have freedom, no freedom at all, no friends or socializing. [They] were unable to play or talk to their neighbors. It’s tough.” Face-to-face social interaction is critical for healthy child development and good mental health.[16] In addition to the consequences for mental health, the lack of recreational opportunities also makes it difficult for children to engage in healthy levels of physical activity, as one Japanese-speaking parent participant said: “The child misses meeting her friends very much. Beside school work, her time is spent on gaming on her iPad most of the day and she has been sedentary.” The need for more family activities that are culturally and linguistically appropriate for refugee and immigrant communities was an important theme that emerged from the interview data.

The “Tri-cultural Myth”

Inequities in language access are partially the result of historic marginalization of many of New Mexico’s diverse communities, which have been influenced and exacerbated by the “tri-cultural myth.” The tri-cultural myth typically characterizes New Mexico’s racial and ethnic identity as white, Hispanic, and Native American. This narrative undermines the pancultural diversity of our state and makes it more difficult for other racial and ethnic communities to be recognized as New Mexicans. The tri-cultural myth has the serious consequence of marginalizing many New Mexicans and promotes racist ideas at all levels of our state government, evidenced by incidents such as when, in 2021, state Senator and Senate Minority Leader Greg Baca questioned whether Sonya Smith, the governor’s Veteran’s Service Secretary-designate, would be able to serve the state’s white, Hispanic, and Native American members as a Black woman.[17]

In addition to such overt acts of racism, there are numerous nuanced ways in which the tri-cultural myth marginalizes communities. One such way is by failing to recognize the diversity within many of New Mexico’s racial and ethnic groups. In an interview during the NMBLC focus group, a Swahili-speaking refugee expressed frustration with how Black Americans and Black Africans are often grouped together when these are distinct communities: “We want to be called Black Africans. Why don’t we have that choice?” Recognizing distinct communities is an important step in making our state more inclusive and dismantling the tri-cultural myth.

It must also be mentioned that even though the tri-cultural myth includes Hispanic and Native American communities in New Mexico’s racial and ethnic identity, significant inequities – including with language access – persist in our state that contribute to health and economic disparities for these groups. Even though New Mexico state law requires special accommodations for Spanish-speakers,[18] the Yazzie/Martinez lawsuit demonstrated how this need is not adequately met. While some accommodations are made for Spanish-speakers in state agencies, few, if any, are made for speakers of Native American or other languages.

The state can help dismantle the tri-cultural myth by requiring its agencies to engage in and support the collection, analysis, and reporting of data measuring socio-economic and health impacts on marginalized populations. The current lack of such data and analysis compound the state’s inability to dismantle barriers faced by New Mexico’s ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse communities with smaller population numbers.

The Added Trauma of Discrimination, Hate, and Violence

As an additional threat to physical and mental well-being, violence and hate crimes against Asian and Pacific Islanders (API) have increased dramatically nationwide due to COVID-related anti-API rhetoric.[19] These hate crimes have also affected API community members in Albuquerque, and one of the study participants at NMAFC reported being assaulted in their workplace: “I have a massage store. My income suffered greatly due to the COVID lockdown and during the pandemic overall. I was also a victim of hate crime. Last December, a customer came into my store without wearing a mouth cover. He got mad because I refused to give service. He assaulted me and called me ‘Chinese virus.’ I suffered multiple injuries to my body and could not work for a month.” Other forms of violence have also been on the rise. One of the caseworkers at NMAFC who serves clients who have experienced domestic violence, sexual abuse, and human trafficking reported that “the pandemic increased the number of victims, and my job got busier compared with before the pandemic.” Domestic violence, sexual abuse, and human trafficking are closely intertwined with the increased rates of economic insecurity brought on by the pandemic, since the lack of resources make it more difficult to avoid and recover from abusive situations.[20] Additionally, due to stay-at-home orders, some of the study participants who are victims of domestic violence were forced to spend more time at home with their abuser.

Policy Recommendations: Addressing Systemic Language Access Barriers

To move forward towards a more inclusive and equitable New Mexico, we need policy reform that addresses the inequities that New Mexicans who speak languages other than English face as a result of the exclusionary language policies and practices in our state. These recommendations should be viewed as complementary to previous recommendations made in the language access-focused health impact assessment conducted by Global 505.[21]

We need more providers, community events that can be either socially distanced or organized safely, access to technology, and help educating new workers in trades to create stable sources of income. There is a lot we need, but at this time I think helping people survive this pandemic.

”

-Caseworker at NMAFC

Widespread Multilingual Interpretation

State agencies, health care providers, and other recipients of federal assistance in New Mexico need to fulfill their obligation to provide multilingual interpretation services for individuals who speak languages other than English, as required by Title VI of the federal Civil Rights Act. Title VI requires that reasonable steps are taken to provide interpretation for individuals who require it. Department of Justice guidance dictates that all recipients of federal funds develop a written plan to provide meaningful language access. Providing multilingual interpretation and translation upon request will help people who speak languages other than English access government assistance, support their children’s success in school, and take advantage of professional development opportunities. The state Legislature should provide state agencies with funding to implement meaningful language access services. Agencies should begin this work by fulfilling the requirement to develop written implementation plans. Where the state is unable to provide interpretation services for a specific language, willing community-based organizations serving that linguistic minority should be funded to do so.

Translation of Materials, Resources, and Documents in Multiple Languages

An important corollary of interpretation is ensuring that all commonly used materials, resources, and documents – including applications for assistance – are translated into multiple languages. The state should, at minimum, comply with Title VI to translate vital documents, working with community-based organizations to determine what is needed. Doing this would allow the many New Mexicans who speak languages other than English to be made aware of the government assistance programs that are available and how to access them when in need of support. Additionally, people should be able to access legally binding contracts in their preferred language so they can fully understand what they are signing. The state should fund willing community-based organizations serving linguistic minorities for their translation services when state agencies are unable to do so.

Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Recreational Activities

Study participants expressed a need for more culturally and linguistically appropriate recreational activities for their families. Such programs would help people in the immigrant and refugee communities feel more connected and would improve their mental and physical health.

Linguistically Appropriate Resources for a Stronger Post-COVID Economic Recovery

The state should recognize the correlation between accessing linguistically and culturally appropriate resources and growing the state economy, particularly within the context of New Mexico’s post-COVID economic recovery. By providing and expanding access to asset-building resources (e.g., Individual Development Accounts, Child Savings Accounts, non-predatory loan options, and refinancing, etc.) the state can frame an equitable post-COVID economic recovery inclusive of all entrepreneurs and small businesses.

Funding to Support Agencies Serving Immigrant and Refugee Communities

Immigrant- and refugee-serving organizations provide essential services for API and African communities, particularly for people who speak languages other than English. These culturally and linguistically competent organizations are well-established and trusted in their communities. The state can support these organizations by providing them with grants to fund and expand the services they provide – many of which the state should already be providing.

Adult Education

Community members and caseworkers both expressed the need for more courses that would teach immigrants and refugees English as a second language, how to use computers and other technology, and the role of government systems such as public education, justice, and health care, as well as how to navigate these systems.

High-Speed Internet

Inequities in high-speed internet access are common throughout New Mexico, in part due to the rural nature of our geographically large, low-population state. One lesson from the pandemic is that broadband internet needs to be as accessible as utilities such as water, electricity, or gas. Ensuring all families have access to affordable broadband internet services is critical for families to succeed in school and participate in the workforce – especially as remote educational and employment opportunities are becoming more commonplace due to the pandemic.

Statewide Data Collection and Language Access Planning and Accountability

Currently, the state does not collect data on language access needs for many non-English speakers. Therefore, an important step in determining how to promote equitable language access is to begin collecting and reviewing available data on these communities. Data collection should lead state agencies to determine to what extent language access deficiencies exist in their programs and develop subsequent plans to address any unmet needs, the progress of which should be measured in yearly assessments. Plans should include strategies that address interpretation and translation needs, as well as training for state agency staff on how to provide language access.

State Advisory Council with Community-Based Organizations

To inform statewide decisions regarding language access, the state should create a language access advisory council with stakeholders such as community-based organizations serving New Mexicans who speak languages other than English. These organizations should be involved in the decision-making process for the development of policies and administrative rules and should represent a diverse spectrum of the languages spoken by the communities they serve. Not only would such a council further efforts around equitable language access but it would also lead to strong partnerships with the community-based organizations, giving the people they serve an ongoing voice in policy- and rule-making.

Clarify Protections that Language Access is a Part of Our State Human Rights Law

Currently, under the New Mexico Human Rights Act, the state prohibits discrimination based on national origin. However, there has not been a clear explanation of how the failure of state agencies to provide language access violates the statute. The state should clarify protections in regulation to include minimum language access requirements under our Human Rights Act.

Yazzie/Martinez Lawsuit and Equitable Education

Language access is an important component of culturally and linguistically appropriate education, as required by the Yazzie/Martinez ruling. The state should continue to follow through with its obligation to provide equitable education for all of New Mexico’s diverse communities. This includes expanding language access for English-language learning students and providing language access accommodations for parents who speak languages other than English, thereby allowing them to equitably participate in their children’s education.

Cultural and Linguistic Competency Training in State Agencies

State agencies should train their employees in how to provide culturally and linguistically appropriate services for New Mexicans who speak languages other than English.

Conclusion: “Everything is in English”

The stories and experiences presented here capture only a small fraction of the systemic inequities that emerged from participant interviews. Although the pandemic helped expose many of these inequities, they are not new. They have been built into the fabric of our society and are root causes of disparities in health and economic well-being for many New Mexicans, including for API and African immigrants and refugees. While programs in the social safety net are designed to benefit people facing hardship, the safety net is also designed in ways that leave many residents excluded. These inequities impact foreign-born New Mexicans who are eligible for benefits but cannot access them due to inadequate language access accommodations. These services not only help immigrants and refugees overcome inequities but help them live healthy and successful lives. Ultimately, gaps in the safety net allow people who need assistance to fall through.

My English is poor, so I relied on my case manager at NMAFC to help me apply for Medicaid and other resources. I could not apply for any assistance on my own since everything is in English.

”

-Chinese-speaking community member served by NMAFC

As referenced throughout the report, community-based organizations currently fill the gaps in language access by providing interpretation and translation services for their clients. These community-based organizations and their caseworkers also play a critical role by supporting their clients in finding health and success in a new country. Caseworkers at these organizations provide comprehensive support for their clients, addressing needs in all aspects of their lives.

During the interviews, multiple study participants articulated the same frustration with our systems of government: “Everything is in English.” The systemic failure to provide multilingual interpretation and translation in state agencies, in the health care system, in public education, and even in the justice system, creates countless barriers for New Mexicans who speak languages other than English. As a direct result, there are communities of New Mexicans who feel isolated and disconnected, who are facing disproportionate hardship during the pandemic, and who are unable to readily access the government assistance for which they are eligible. It is incumbent upon the state to improve equitable language access in New Mexico in order to give all New Mexicans the best opportunities to participate in our democracy and live healthy and successful lives.

Endnotes

[1] “Immigrant Health in Rural Maryland: A Qualitative Study of Major Barriers to Health Care Access,” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19, 939–946, 2017

[2] “Perceived barriers in accessing food among recent Latin American immigrants in Toronto,” International Journal for Equity in Health, 12, 1, 2013

[3] “The Limited English Proficient Population in the United States,” Migration Policy Institute, 2015

[4] “Judge rules New Mexico violates public school students’ constitutional right to sufficient educational opportunities,” NM Center on Law and Poverty, 2018

[5] “Barriers to School Involvement: Are Immigrant Parents Disadvantaged?” Journal of Educational Research, 102, 257–271, 2009

[6] “Alone in a Crowd: Indigenous Migrants and Language Barriers in American Immigration,” Race and Justice, 2021

[7] “Barriers to participation in the food stamp program among food pantry clients in Los Angeles,” American Journal of Public Health, 96, 807–809, 2006

[8] “Millions of U.S. voters risk missing the historic 2020 election because their English isn’t good enough,” WHYY, 2020

[9] “About Half of Lower-Income Americans Report Household Job or Wage Loss Due to COVID-19,” Pew Research Center, 2020

[10] “Low-wage, low-hours workers were hit hardest in the COVID-19 recession,” The State of Working America: 2020 Employment Report, Economic Policy Institute, 2020

[11] “Immigrant Workers in the Hardest-Hit Industries,” New American Economy, 2020

[12] “The Digital Divide Hits U.S. Immigrant Households Disproportionately during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Migration Policy Institute, 2020

[13] Memo for NM Voices Report on Language Access, NM Center on Law and Poverty, 2021

[14] “Parental involvement of immigrant parents: a meta-synthesis,” Educational Review, 71, 362–381, 2019

[15] “When Only Family Is Available to Interpret,” Pediatrics, 143, 2019

[16] “The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health,” The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, 4, 634–640, 2020

[17] “New Mexico state senator faces criticism over questioning of Black Cabinet nominee,” Santa Fe New Mexican, 2021

[18] “Spanish not ‘enshrined’ as official N.M. language,” Albuquerque Journal, 2013

[19] “The Rise In Anti-Asian Attacks During The COVID-19 Pandemic,” National Public Radio, 2021

[20] “The Role of Sexual Violence in Creating and Maintaining Economic Insecurity Among Asset-Poor Women of Color,” Violence Against Women, 20, 1299–1320, 2014

[21] “Language Access as a Bare Minimum to Support Health of Immigrant and Refugee Families,” Global 505: Health Impact Assessment, 2018