A Working Poor Families Project report

Download this report with its appendices (Dec. 2011; 20 pages; pdf)

Introduction

Introduction

New Mexico faces something of a catch-22 when it comes to improving the educational levels of its workforce. The state’s workforce has lower-than-average levels of education, which has led to a higher-than-average percentage of low-wage jobs. Given our lower wage levels, our workers are less able to afford to get more post-secondary education. Hence, our state is less able to attract high-wage jobs.

New Mexico’s state government has long worked to make a post-secondary education readily available, and the state has an extensive system of universities, branch campuses, and community colleges to show for it. New Mexico has also kept tuition rates relatively low. That these measures have not translated into a well-educated workforce should be an issue of serious concern for policy-makers. When pursuing the answer, however, they must consider that the problem of workforce education begins long before New Mexicans reach working age.

In 1996, the state created a lottery scholarship for high school graduates. The scholarship covers a student’s tuition at a New Mexico university providing the student graduates from a New Mexico high school, begins college the following semester, and maintains a certain grade point average. The lottery scholarship was a great success in that it increased enrollment of new students. However, the state found that many of these students were academically unprepared for the rigors of college curriculum and many schools had to expand their remedial course programs. New Mexico’s high schools were not preparing their students for a post-secondary education even though they’d put a mechanism in place to pay for one.

If New Mexico’s young adults are not prepared to pursue a post-secondary education when fresh out of high school, it is not likely that those New Mexicans already in the workforce are any better prepared. They are also no longer eligible for the lottery scholarship and are more likely to have greater financial obligations—such as a family to support and rent or mortgage—than they did in their teens. For the high percentage of New Mexicans who do not graduate from high school, the odds of improving their economic situations as adults are even worse.

It is unlikely, however, that the lottery scholarship will be expanded to include non-traditional students. In fact, recent tuition increases have begun depleting the lottery scholarship fund. Even with no further tuition increases, the fund will be on the verge of depletion at the present rate of expenditure by the end of FY14.

It is clear that in addressing the issue of workforce education and college affordability in New Mexico, policy-makers need to look at a multi-faceted approach.

New Mexico’s Workforce

The problem of post-secondary education and its affordability in New Mexico is easily put into perspective with U.S. Census data extracted by the Working Poor Families Project: in 2009, New Mexico had 1.23 million people aged 18 to 64—the age group most likely to be active in the workforce. Of that population, more than a half-million (533,960 people) had no post-secondary education. With a rate of people with no post-secondary education at 43.4 percent—a percentage well above the national average—New Mexico ranked 35th in the nation, meaning only 15 states were doing worse.

When looking just at the percent of New Mexico adults aged 18 to 64 who were without a high school diploma or a GED (16.4 percent) New Mexico ranked even lower at 46th. Another 27 percent of adults had only a high school diploma, and about 30 percent had an associate’s degree or higher, ranking the state 39th by this measure. Given these rankings, it’s no wonder we have a difficult time recruiting high-wage industries to the state.

Language fluency and literacy are also problematic. A little more than 10 percent of New Mexico adults speak English “less than very well,” which is a definite barrier to advancing in the labor force in an English-speaking country. About 43 percent of adults function at the “basic” or “below basic” level of literacy. Another telling statistic is that only 34 percent of young adults aged 18 to 24 are enrolled in a post-secondary institution. New Mexico ranks 48th by this measure.

Education, Job Growth, and Unemployment Rates

The level of education in each state affects more than that state’s economic development. It also has a direct impact on economic outcomes such as the unemployment rate and employment growth. There is a strong inverse relationship between the level of education and the unemployment rate—the lower the education level, the higher the unemployment rate. In 2009, the unemployment rate for people with less than a high school education (13.7 percent) was more than triple the rate for those with a graduate or a professional degree (3.4 percent) in a field like law or medicine. Filling out the middle, the unemployment rate was 9.3 percent for those with a high school diploma or GED, 7.3 percent for those with some college, 6.1 percent for those with an associate’s degree, and 4.2 percent for those with a bachelor’s degree.

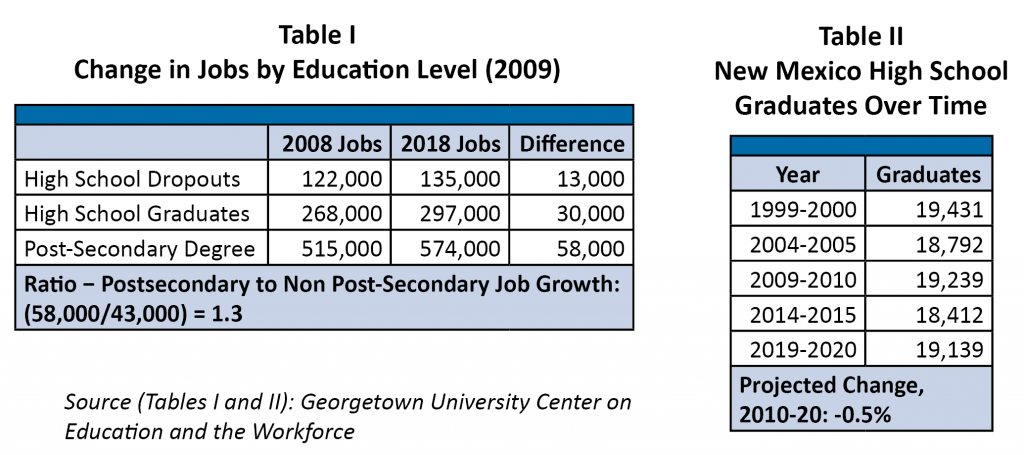

Job growth is inversely related to educational levels for the next several years, as job demand is shifting to jobs requiring a post-secondary education. Over the 2008 to 2018 period, the demand for jobs requiring post-secondary credentials will outpace jobs requiring only a high school diploma by almost 30 percent. Table I shows that New Mexico will add 43,000 jobs requiring non-secondary and secondary education. Sectors requiring workers with post-secondary preparation, including associate’s degrees, will add 58,000 jobs.

Table II shows that the number of high school graduates in the labor force pipeline will begin to decline over the 2010 to 2020 period, even as overall population—and one expects, employment—continues to rise. This shortage will put pressure on employers to increase wages. An emerging scarcity of workers should lead state policy-makers and the education system to better prepare the workers we have for the workforce. With a growing shortage of workers, productivity will also need to increase. Increased productivity will result from employers shifting to more “capital intensive” ways of producing goods and services—using machinery instead of workers—as workers become more expensive and valuable.

The condition of the labor market in New Mexico has been slack in the current recession, with supply outpacing demand, giving employers a bargaining advantage over workers on wages and benefits. The tightening of the labor market over time will give employees more of an edge. Non-traditional higher education students will become more prevalent as the labor market tightens and the need for higher productivity brings about more investment in the human capital (i.e. education and training) of an aging work force.

Higher Education and the Recession

Despite the disappointing education level of our workforce, New Mexico makes an impressive investment in higher education compared to the national average. In fact, New Mexico ranks 11th among the 50 states in terms of expenditures per full-time equivalent (FTE) student, spending 18 percent more per FTE than the national average. In FY10, New Mexico spent $7,589 per FTE, while the national average was $6,454. The only states spending more per FTE than New Mexico were Alaska, Connecticut, Idaho, Illinois, Mississippi, Nevada, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming. Almost all of these states are far wealthier than New Mexico and, with the exception of Mississippi, all of these states have higher per capita income than New Mexico.

As could be expected, higher education enrollment has risen rapidly during the current economic downturn. This results from students staying in school longer and workers returning to school to improve their employability. In New Mexico, however, enrollment far outpaced national growth rates. According to the State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO) annual report, State Higher Education Finance, FY 2010, New Mexico higher education enrollment on a FTE basis rose by nearly one-quarter between FY05 and FY10 (from 79,219 students in FY05 to 89,450 in FY09, and 98,710 in FY10). Between FY09 and FY10 alone, there was a 10.4 percent increase in enrollment. In the country as a whole, FTE enrollment was up 14.9 percent between FY05 and FY10 and just 6.3 percent between FY09 and FY10.

However, just as the recession led to an increase in higher education enrollment, it also necessitated a decrease in the state’s investment on an FTE basis. Educational appropriations per FTE dropped 20 percent between FY05 and FY10 (from $9,481 to $7,589 in constant 2010 dollars). As with enrollment growth, the decline in appropriations accelerated between FY09 and FY10. State funding dropped more than 10 percent (from $8,472 to $7,589) in just two years. The national average decline in appropriations by FTE was 7.2 percent over the five year period and 3.1 percent between FY09 and FY10 (from $6,662 in FY05 to $6,591 in FY09, and $6,454 in FY10).

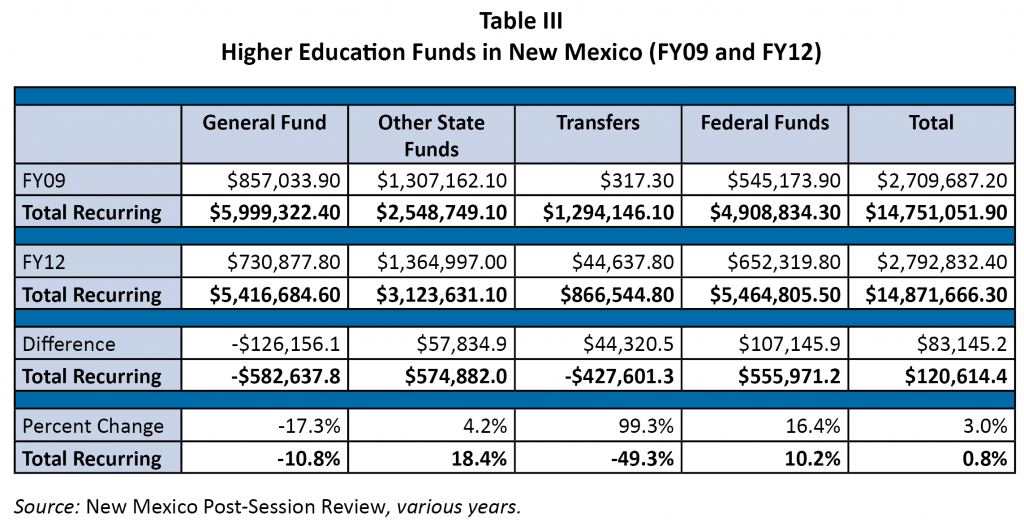

Even as state expenditures by FTE were dwindling, overall higher education expenditures in New Mexico rose slightly (3.1 percent or by $83.1 million) between FY09 and FY12, from $2.709 billion to $2.79 billion. Higher education spending in New Mexico was shielded from the full force of the recession during these years because of an increase in federal funding and tuition hikes.

Higher Education Expenditures and Revenues

The most useful way of viewing expenditures in post-secondary education is by looking at total budgeted higher education expenditures from all sources of funds. Expenditures from all funds include the state general fund, revenues from tuition and other fees and charges, and federal funds.

Overall, total state general fund revenues fell by one-fifth as the recession descended on New Mexico (from $6 billion in FY08 to $4.8 billion in FY09). In response, state general fund revenues directed to higher education dropped drastically—17.3 percent—between FY09 and FY12, a fall of $126 million (see Table III). Higher education revenues coming from ‘other state funds’— which includes tuition—rose from $1.307 billion to $1.364 billion (or 4.4 percent) as state policy-makers chose to shift the cost to students by raising tuition.

Through the federal Recovery Act (or ARRA), the contribution of the federal government rose steeply—about 20 percent—from FY09 to FY12 (from $545.2 million to $652.3 million for an increase of $107.1 million). The federal government’s contribution slowed between FY11 and FY12, but still rose by 6 percent in the current budget year. The recession has taken a severe toll on the higher education budget in New Mexico. If the federal government’s increase funding had not been so large, the state would have been faced with an even more unpalatable choice of cutting spending or increasing student costs.

Appendix A of the FY10 SHEEO report presents a table showing state support for higher education for fiscal years 2006, 2009, 2010, and 2011. The last two years are atypical because of the money from the federal Recovery Act of 2009 that flowed to higher education to replace state funds. The FY06 expenditures are presented as a benchmark to assess the long-term trend in expenditures for higher education. In FY06, New Mexico spent $837.1 million in state money on higher education. In FY09, before Recovery Act money started coming, New Mexico budgeted $994 million on higher education.

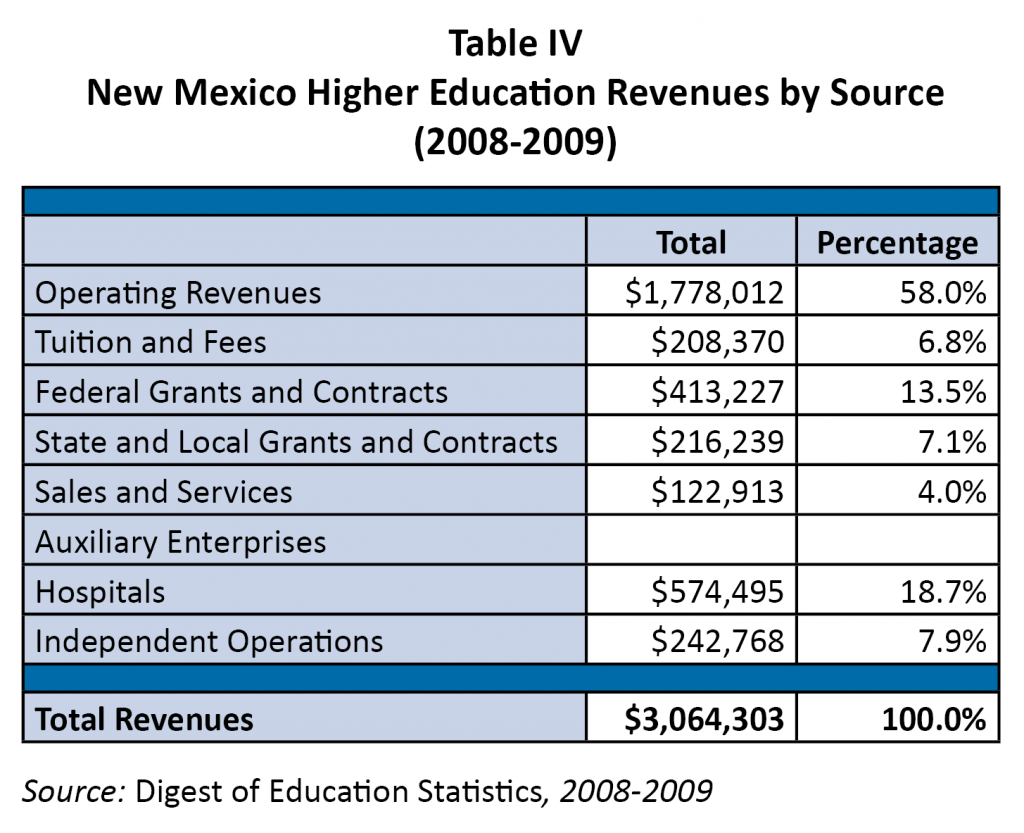

The Digest of Education Statistics provides a breakout of higher education revenues by source. According to this source, higher education in New Mexico received $3.064 billion in total revenues in FY09 (see Table IV). Of that amount, $1.778 billion (or 58 percent) was operating revenue, $208 million (or about 7 percent) came from tuition, and federal grants and contracts accounted for $413.2 million (or 13 percent) of total revenues.

Affordability: Tuition and Financial Aid

Perhaps because New Mexico spends generously on higher education on an FTE basis, tuition at higher education institutions is lower than the national average. New Mexico costs in FY10 were only 40 percent of the national average, even though it had risen by 34.5 percent in the preceding five years. Tuition per FTE in New Mexico rose 40 percent between FY05 to FY09 (from $1,300 to $1,851), then declined 5.5 percent in FY10 (to $1,749). Compared to the national average, New Mexico still has modest tuition costs for students. New Mexico, however, is a very low-income state (as measured by per capita income) so it seems reasonable that tuition costs should be low.

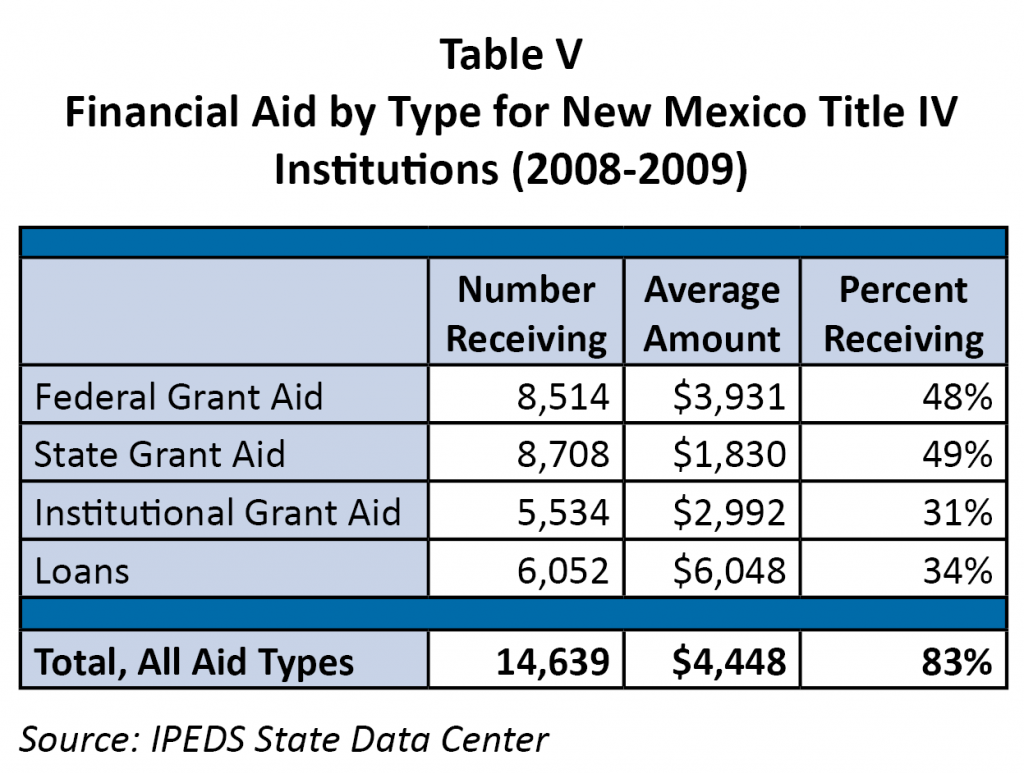

In New Mexico’s Title IV institutions, there were 14,639 people—about 83 percent of the student population—receiving financial aid. The average amount received was $4,448 (see Table V). Of that number, 8,514 (or 48 percent) were receiving federal grants with an average amount of $3,831.

A Title IV institution is defined as: “an institution that has a written agreement with the

[US] Department of Education that allows the institution to participate in any of the Title IV student financial assistance programs…” There were 41 Title IV higher education institutions in New Mexico in 2008-09: 28 public, three private non-profits, and 10 private for-profit schools.

Appendix I, II and III present a comprehensive picture of financial aid for all post-secondary students in New Mexico (including out-of-state students in Appendix II and III). Overall, there were about 54,400 students receiving New Mexico sponsored financial aid during FY10 for a total allocation of about $93 million. Federal expenditures on financial aid were far higher than aid from the state of New Mexico: 140,000 recipients and expenditures of $522 million. New Mexico expenditures on New Mexico students were $92 million on 53,100 students.

Solvency of the Lottery Scholarship Program and Fund

The New Mexico Legislative Lottery Scholarship accounts for about 80 percent of state merit-based student scholarship expenditures. However, the sustainability of the scholarship has recently come into question due to trends in revenues and expenditures. A gap is emerging between the supply of Lottery Scholarship dollars and the demand for the scholarship from New Mexico students. Tuition increases at the state’s higher education institutions have the effect of depleting the Lottery Scholarship fund. That is, the Legislature’s attempts to shift more of the cost of the state’s higher education programs to students have the effect of damaging the solvency of the Lottery Scholarship fund.

On July 25, 2011, the Legislative Education Study Committee (LESC) issued a staff brief on the solvency of the Lottery Scholarship fund under a range of scenarios for tuition increases at New Mexico’s higher education schools. The LESC’s report provides graphs of three Lottery Sustainability Models, provides tables showing projections of Lottery Scholarship fund solvency under three tuition increase scenarios, and compares FY11 to FY12 tuition and fees at New Mexico’s higher education institutions.

The Legislative Lottery Scholarship Sustainability NM Higher Education Model (see Appendix IV) compares the Lottery Scholarship fund balance at the beginning of each fiscal year. Each panel of the table shows the fund balance at the beginning of the fiscal year, the lottery income, interest on the fund, expenditures, and ending balance for the fiscal years between 2009 and 2014. In the first two years, the change was fairly gradual. However, even with no tuition increases, the fund would be on the verge of depletion at the present rate of expenditure by the end of FY14. The Higher Education Model shows that, at the end of FY14, the fund would be in deficit by $9.4 million with a tuition increase of 5 percent; $13 million with a tuition increase of 7 percent; and $16.6 million with tuition increase of 9 percent.

The final table of the LESC report, FY11 to FY12 Tuition and Fees Comparison (see Appendices V and VI), shows that undergraduate resident fees increased by 6.9 percent at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, 7.9 percent at New Mexico State University, and by 6.8 percent at the University of New Mexico. Statewide, the undergraduate tuition increase between FY11 and FY12 was 10 percent. It is clear that there are looming problems ahead for the New Mexico Lottery Scholarship.

A June 15, 2010, memorandum from the staff of the Legislative Study Committee to the LESC, made several recommendations to tighten eligibility requirements for receiving the Lottery Scholarship. The recommendations were made in the context of expected constraints on Lottery Scholarship funding availability. The LESC staff recommendations fell under two headings: increasing the merit-based requirements and establishing a scholarship-for-service program. Under increasing the merit-based requirements, the LESC staff proposed requiring a more rigorous high school curriculum for recipients and/or allocating the Lottery Scholarship on a sliding-scale based on a student’s GPA. The scholarship-for-service concept would use the existing model of scholarships for students in the health care field for qualifying for the Lottery Scholarship.

A policy that was not mentioned in the LESC staff report was changing the Lottery Scholarship eligibility criteria from a merit basis to a need basis. The basic criteria could be shifted from a merit basis to a need basis entirely or by blending merit-based criteria with need-based criteria. The concept of a lottery scholarship determined by need-based eligibility could utilize the existing FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) structure.

Costs versus Income

Despite the lower rates of tuition and the prevalence of financial aid programs, the cost of a post-secondary education is still out of reach for many New Mexico workers, particularly when the cost of child care and lost wages are figured in.

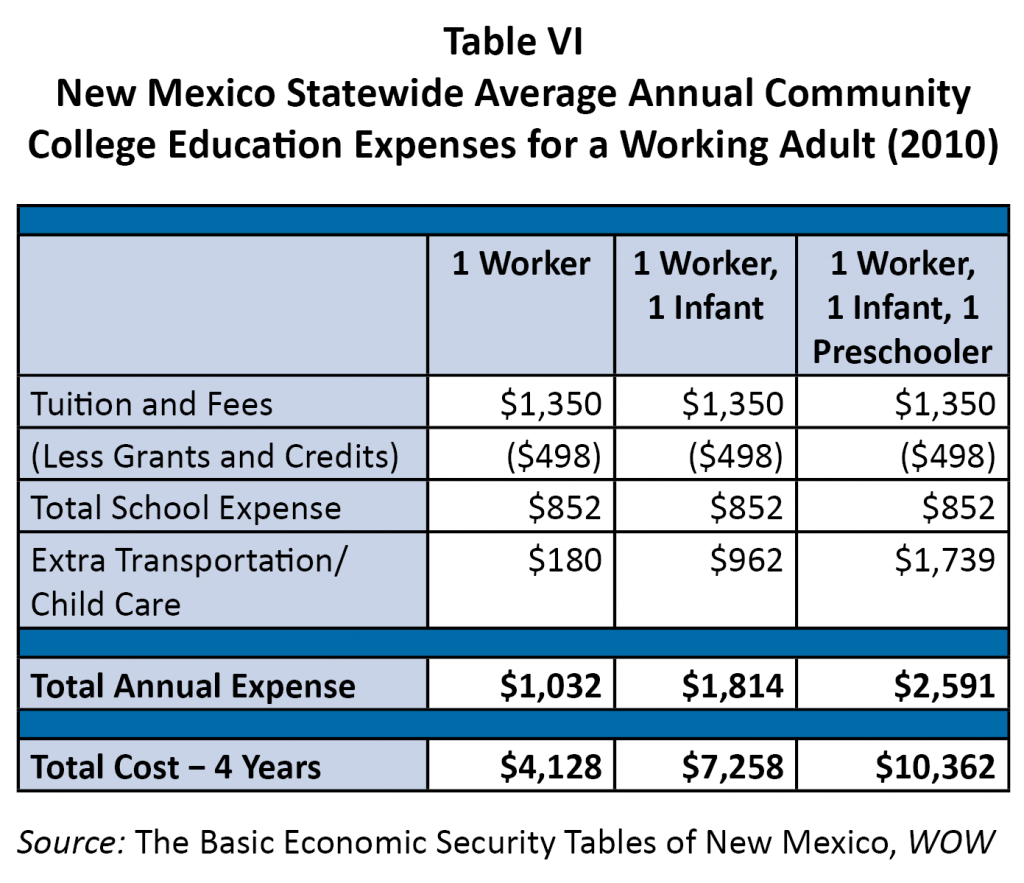

The Basic Economic Security Tables for New Mexico, a project of Wider Opportunities for Women’s (WOW) economic security programs, provides an estimate of the cost of adult education and training expenses. The estimate is for three categories of workers—two with small children and one without—for a statewide average of the cost of community college education. According to this report, community college degrees commonly boost earnings by 20 to 30 percent.

For one single full-time worker who attended a New Mexico community college half time in 2010 the annual cost was $1,032, totaling $4,128 over four years. For a worker with an infant (not an unusual situation) the annual cost was $1,814, or $7,258 for four years. The cost rises to $2,591 a year and $10,362 for a 4-year program for a single worker with an infant and a preschooler. The cost of community college education should also include the income foregone by dropping hours worked by half. Given these circumstances, the cost of attending community college is fairly high, and probably constitutes a barrier for most working parents.

WOW’s Family Economic Security Program has produced estimates that provide statewide and county basic economic security tables for several family configurations for 2010 (see Table VI, page 9). As part of this study, WOW produced a table estimating the annual and 4-year cost of community college for a family of one worker; one worker with one infant; and one worker with one infant and one preschooler. The added cost for the worker with a child or two includes paid child care and extra transportation to and from the child care facility. Transportation and child care rises from $180 for one worker, to $962 for one worker with an infant, and $1,739 for one worker with an infant and preschooler.

The income level needed to provide basic economic security is $21,888 for one worker with employment-based benefits; $34,296 for one worker with an infant; and $47,174 for one worker with a preschooler and school-age child. Community college expenses would eat up 5 percent of incomes.

At least one-fifth of all New Mexico families had incomes lower than $25,000, according to Working Poor Families Project special data runs from the US Census’ American Community Survey. A family income below $25,000 represents economic hardship. Another 52,000 families, or nearly 10 percent of total families, had incomes between $25,000 and $35,000, which is certainly a level of income that indicates economic stress. Attendance at community college and working part time may be simply beyond the reach of many lower-income families. And if lower income is defined as less than $35,000, this represents almost one-third of New Mexico families.

Key Findings and Policy Recommendations

Since New Mexico already makes a very large investment in post-secondary education, there is a disconnect between amount of money spent and outcomes in the way of an educated work force. Even given the state’s level of investment, a college education may still be too costly, particularly for our lowest-income workers and workers with young children. The need for remedial courses may prolong the time a student spends in college, which will drive up costs. Such students may also conclude that a post-secondary education is simply beyond their reach intellectually because they did not receive the necessary background in high school.

College Affordability Fund

One way New Mexico could improve affordability for low-income workers is to expand the College Affordability Fund, which provides tuition assistance to those who have been out of school for more than a year and may not qualify for a merit scholarship. Eligibility could be broadened in a number of ways:

- Currently, a student must be enrolled at a four-year college or university to receive assistance from the College Affordability Fund. Expanding eligibility to include degrees or professional certificates from two-year colleges would open the fund to include a whole new range of students, putting a post-secondary education more readily within their reach.

- Currently, a student must remain enrolled at least half time. Eligibility should be expanded to allow students to take fewer courses to more easily fit school into work schedules.

- Currently, awards are limited to $1,000 per semester and $2,000 per year. The amount of funds available per semester and year should be expanded.

- Currently, part-time students receive a pro-rated amount (no more than $750 for students enrolled three-quarters time and $500 for half time). The pro-rated amount should be expanded to match the true cost of part-time coursework.

- Improving outreach to students and simplifying the procedures used by agencies that administer the fund would also allow it to reach more students.

Lottery Scholarship

Given increases in tuition, the Lottery Scholarship is quickly running out of funding. Changes should be made so that it better serves the students who need it most:

- The Lottery Scholarship could be need-based and the award amount could be expanded for those who qualify to help meet other costs such as fees, books, and living expenses.

- Currently, only those who just graduated from high school are eligible for the Lottery Scholarship. Eligibility could be expanded to include low-income young adults who did not attend college right out of high school.

Child Care Assistance

Policies to make college more affordable for working adults must include increased child care assistance. Parents must have safe, reliable and affordable child care not just for the hours they are in class, but for necessary study time as well. However, budget shortfalls due to the recession have taken a heavy toll on New Mexico’s child care assistance program. Currently, only families living in deep poverty are eligible for new enrollment in the program. Those who would have been eligible just a few years ago have been placed on a waiting list, which has grown to include several thousand children. Child care assistance should be expanded in a number of ways:

- Eligibility should be set at 235 percent of the poverty level, as it was when the program was fully funded prior to the recession.

- Eligibility should be higher for parents who are pursuing a post-secondary education at least half time.

- Payments to providers should encourage higher standards of quality so children are getting appropriate child development experiences. The higher the quality of care, the more likely children will be set on the path to their own future academic success.

Employer-based Training and Education

Employers could be engaged in retaining and improving their workforce by investing in their workers’ education. The state should encourage an expanded use of successful job training incentive programs and work-skill development programs to expand the flexible skill base of their employees. This can not only serve to help employees pay for higher education, but can lead to higher wages for the worker as well as build capacity for the employer to expand the services they offer. Employer-based training can be linked to post-secondary education in a number of ways:

- Employers could be encouraged to invest in worker education that leads to credentials and degrees by subsidizing tuition at post-secondary institutions.

- The state should assure that any state-funded worker training awards credits that lead to post-secondary degrees and credentials.

Download this report with its appendices (Dec. 2011; 20 pages; pdf)

The Working Poor Families Project is funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Ford Foundation, Joyce Foundation, and The Kresge Foundation.