Download this report (Dec. 2011; 8 pages; pdf)

Find more data for New Mexico and the nation on the KIDS COUNT Data Center

New Mexico’s Home Visiting/Parent Mentoring Programs

New Mexico’s Home Visiting/Parent Mentoring Programs

Extensive research and practice show that providing for healthy early childhood development and learning—from before birth through age five, and especially through age three—yields sizeable cost-savings for states and far-reaching educational, economic and social benefits for children, families and communities. Programs like home visiting/parent mentoring are shown to have long-term positive effects on education and health, as well as improve the state’s workforce. This is demonstrated in a report from New Mexico’s Children, Youth and Family Department (CYFD), 2010 New Mexico Home Visiting Statewide Needs Assessment (HVNA). The report states that, “universal access to a coordinated continuum of high quality home visiting services that are embedded in a high quality early childhood system that promotes maternal, infant, and early childhood health, safety, development, and strong parent-child relationships will be especially beneficial for New Mexico’s” families.1

Unfortunately, New Mexico has a long way to go to reach the goal of serving all families in need. The report notes that there were 29,000 births in 2009, yet only 4,400 families were served by 53 home visiting programs, constituting “an extremely high level of unmet need.”2

Home Visiting and the “Building Blocks” of Learning

Voluntary, early home visiting programs team up parents who are expecting a child or have a newborn with a trained professional/paraprofessional who provides tailored information and support services up to the child’s third year.3,4 Services include: basic medical care for pregnant women; education on parenting, child development, and life-skills; child abuse prevention; and referrals to community services and resources, including health screenings and/or well-child visits.5

Home visiting (HV) programs that support children’s development up to age three are extremely important because most of a child’s brain development occurs before age five.6 From a very early age, children develop basic skills—like impulse and emotional control, paying attention, and remembering and using information—from their parents and others, through modeling, practice, and experience.7,8 These are considered the “building blocks” of learning. By age one, toddlers should show budding capacity in these skills; by age three they should be able to finish simple tasks, focus, and remember rules needed to solve problems. Children coming to kindergarten who can “follow and remember classroom rules, control emotions, focus attention, sit still, and learn on demand through listening and watching” do better on reading and math tests and have better social, emotional, language, and learning outcomes.9,10,11

Decades of research show strong evidence that home visiting positively affects parent practices—which impact early development and child well-being.12,13 We know that:

- Children in HV programs carry throughout their lives lasting gains in educational attainment, pro-social behavior, and better paying jobs, and have less need for special education placement and grade retention.14,15,16

- Early childhood HV programs help prevent child abuse and neglect, reducing rates by up to 80 percent among low-income families.17,18,19,20

- HV programs reduce rates of low birth weight babies (saving from $10,000 to $40,000 in medical costs for each child), as well as later rates of juvenile arrests, teen births, substance abuse, and behavioral problems.21,22

- Most effective HV programs focus on low-income, first-time and/or adolescent mothers, start services during pregnancy, provide four or more visits per month for more than a year, and employ highly-trained, well-supervised, culturally-sensitive—and well-compensated—home visitors.23,24,25,26

Where the Needs Are Greatest—and the Programs Fewest

Where children live, work, play, and learn has a great impact on their lives. Safe communities with ready access to high-quality prenatal and early child care services, schools, and health care facilities, as well as solid job opportunities and low levels of poverty, are positive environments in which to raise healthy children. High-quality early childhood care and education (ECE) services—including home visiting—help overcome barriers and disadvantages for children not fortunate enough to be raised in such environments. But New Mexico’s communities that are the most vulnerable and have the fewest resources for families are not necessarily where most HV programs are located.

As budgets are limited, it makes sense to determine where the most vulnerable or at-risk communities are—where the need for ECE services is greatest—to better allocate resources and provide equitable opportunities for children in these areas to thrive.

CYFD’s HVNA report identified 53 programs in 24 of the state’s 33 counties that meet the federal Affordable Care Act’s definition of quality home visiting. To identify New Mexico counties most in need of home visiting services—that is, counties in which more barriers to children’s healthy development exist—the HVNA ranked the counties by how each fared in terms of selected key indicators (or social determinants) of risk. Certain indicators—rates of premature birth, low birth weight, infant mortality, child abuse/neglect, and family  poverty—not only reveal how many children are at risk of hardship, death or developmental delays, but also confirm the presence of socio-environmental factors that negatively influence those rates. Other indicators, like high rates of unemployment, high school dropout, juvenile arrest, and/or teen births, reveal that families are suffering the consequences of having been brought up in resource-poor environments. By analyzing these data for all counties, then ranking the counties by their accumulated levels of risk, the HVNA team identified Quay, Grant, Guadalupe, Lea, Luna, Cibola and McKinley counties, as well as Albuquerque’s South Valley/South Central area, as being at greatest risk for raising children in a good learning environment, and therefore having the greatest need for home visiting programs. Based on the report, CYFD plans to use the funding to pilot two evidence-based home visiting models in Quay, Grant, McKinley and Luna counties, and Albuquerque’s South Valley.27

poverty—not only reveal how many children are at risk of hardship, death or developmental delays, but also confirm the presence of socio-environmental factors that negatively influence those rates. Other indicators, like high rates of unemployment, high school dropout, juvenile arrest, and/or teen births, reveal that families are suffering the consequences of having been brought up in resource-poor environments. By analyzing these data for all counties, then ranking the counties by their accumulated levels of risk, the HVNA team identified Quay, Grant, Guadalupe, Lea, Luna, Cibola and McKinley counties, as well as Albuquerque’s South Valley/South Central area, as being at greatest risk for raising children in a good learning environment, and therefore having the greatest need for home visiting programs. Based on the report, CYFD plans to use the funding to pilot two evidence-based home visiting models in Quay, Grant, McKinley and Luna counties, and Albuquerque’s South Valley.27

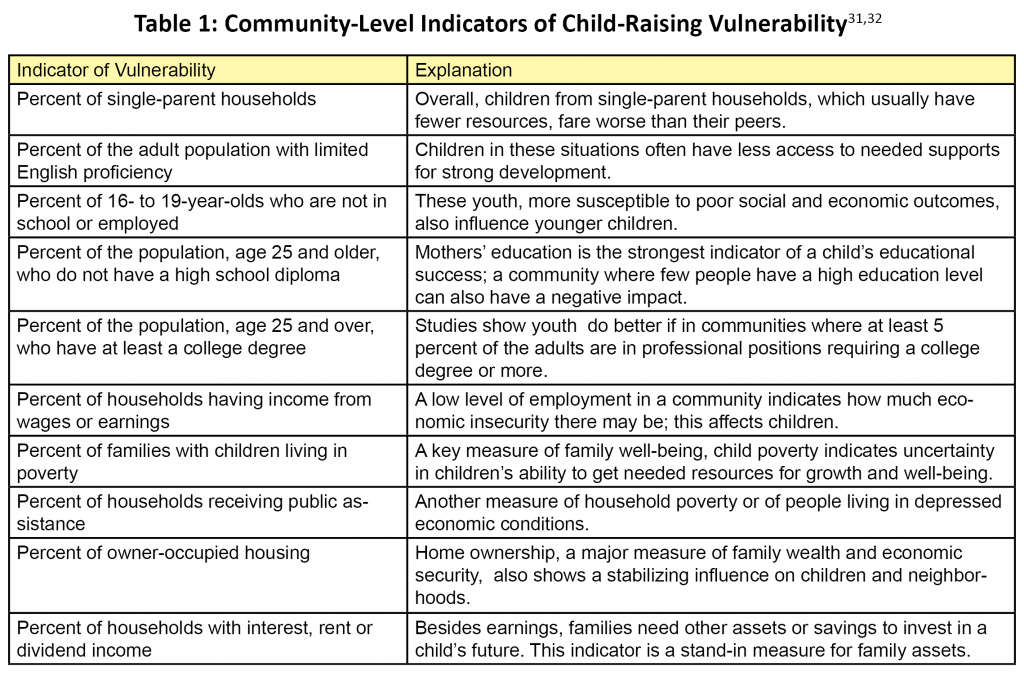

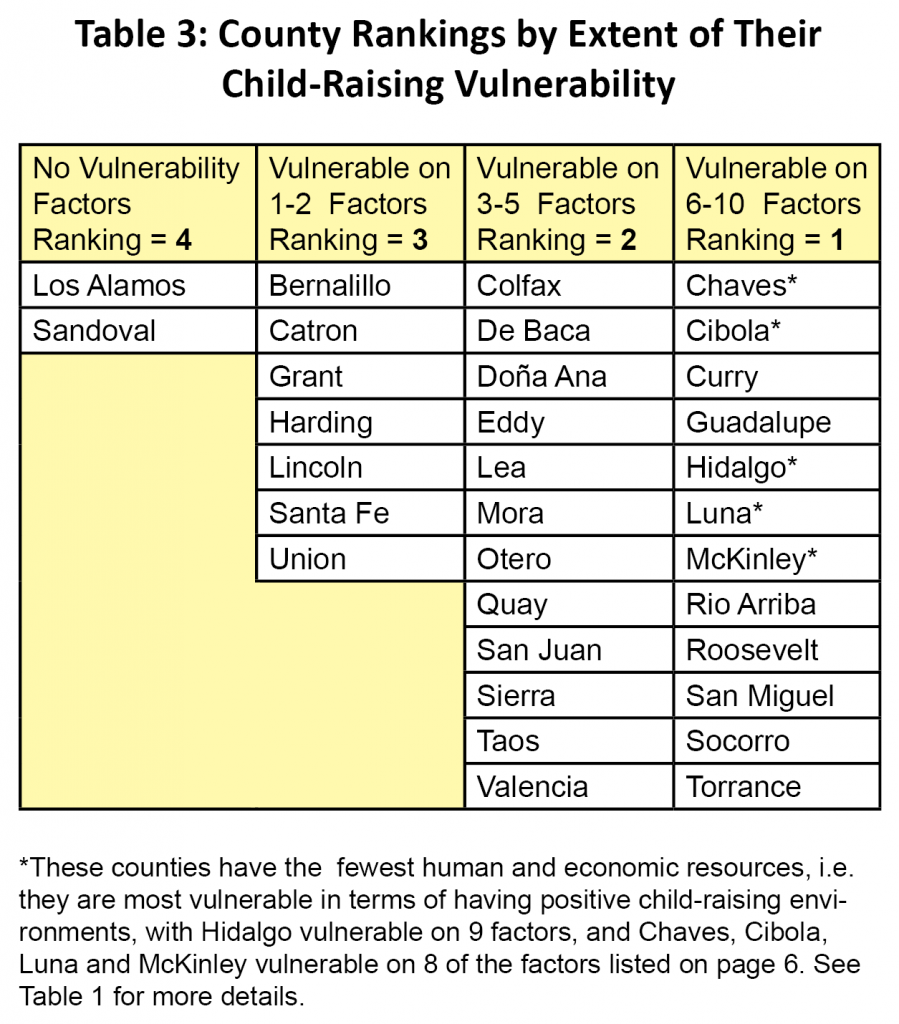

Other risk factors and rating systems can help us get an even clearer perspective of counties in need of ECE, specifically home visiting. The national Child and Family Policy Center and the State Early Childhood Policy Technical Assistance Network created another geographic “child raising vulnerability” rating system based on research showing that certain key, interconnected factors help predict child growth and success, in the report Village Building and School Readiness: Closing Opportunity Gaps in a Diverse Society.28 (See factor list in Table I.)

Use of this rating system across states showed that urban areas have the highest levels of child-raising vulnerability, i.e. communities in which there were higher levels of poverty or economic need and lower levels of assets and education. The Western region (including New Mexico) is ranked second in terms of great vulnerability. In the nation as a whole, New Mexico also ranked fifth among the ten states with the highest percent of non-metro tract populations that face barriers to healthy child-raising.

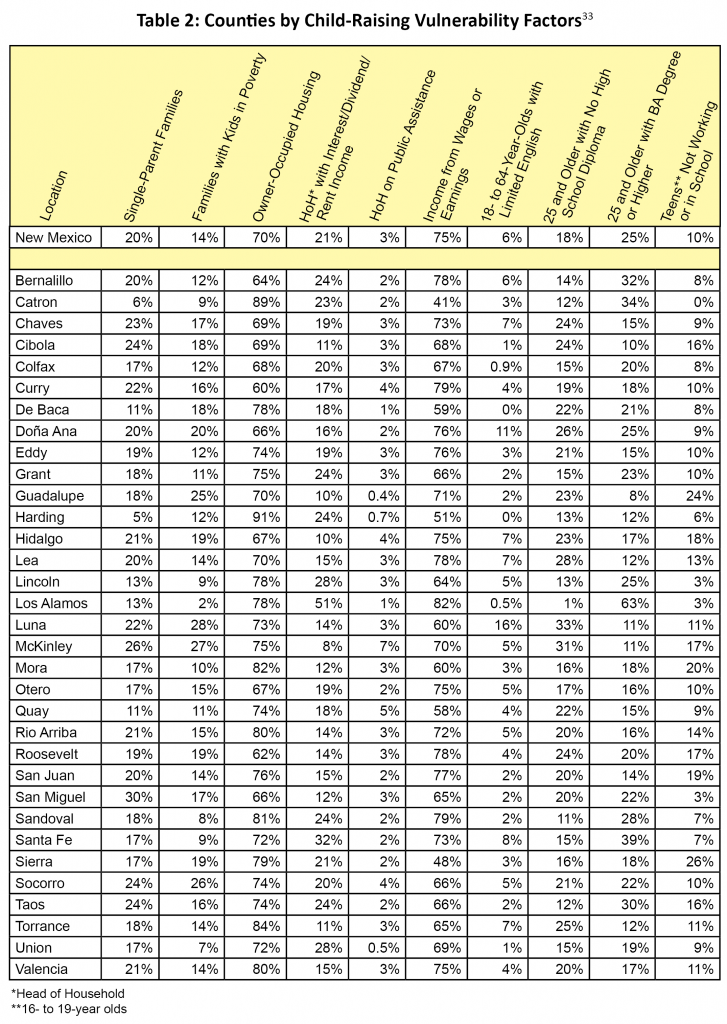

This KIDS COUNT report ranks New Mexico counties using the vulnerability index in the Village Building and School Readiness report. A simple method of comparison was used; since New Mexico itself ranks among the states in which children are most vulnerable to negative influences, the state’s status on each indicator was used as the baseline against which to compare the counties. Any county with a lower performance level than the state as a whole was considered to be at an even higher rate of child-raising vulnerability than the state on that measure. (See Table 2, for a summary of state and county data showing counties most at risk.)

For example, San Miguel County has a higher percent of single-parent families (30 percent) than New Mexico (20 percent) does, putting it at a higher risk or vulnerability for raising children on this indicator. Any county with worse data than the state as a whole on six or more of these indicators is at the highest level of “child raising vulnerability”—in that several educational, economic, and social resources are limited and/or weak. (See Table 3.) Any county, such as Los Alamos, which performs better on these indicators than the state, is considered less vulnerable—one in which the environment is better for raising children well.

To make matters worse, four of the counties in which families of young children face six or more conditions that limit or get in the way of positive growth and well-being (Curry, McKinley, Rio Arriba and Roosevelt) also have a higher proportion of children between ages zero and five—their prime early learning years—within their overall population than the state does as a whole. In addition, among those counties with greater vulnerability, most have a high level of first-time births, especially to single mothers and/or to teens—all of which are associated with disadvantages when raising a healthy child. Examples include:

- Chaves County: 37 percent of births (383 babies) were first-borns in 2009; 56 percent of these were to single mothers, and the teen birth rate (2010) was 62 per 1000 teens ages 15 to 19—yet only 8 percent of families with newborns were served by home visiting programs;

- Curry County: 40 percent of births (338 babies) were first-borns in 2009; 47 percent were born to single mothers, and the 2010 teen birth rate was 79 per 1000 teens—but only 4 percent of families with a newborn took part in home visiting;

- McKinley County: 35 percent (473 babies) of births were first-borns (2009); 72 percent of these were to single mothers, and the 2010 teen birth rate was 46 per 1000 teens—with 11 percent of families with newborns served by a home visiting program.

Not Reaching Minorities

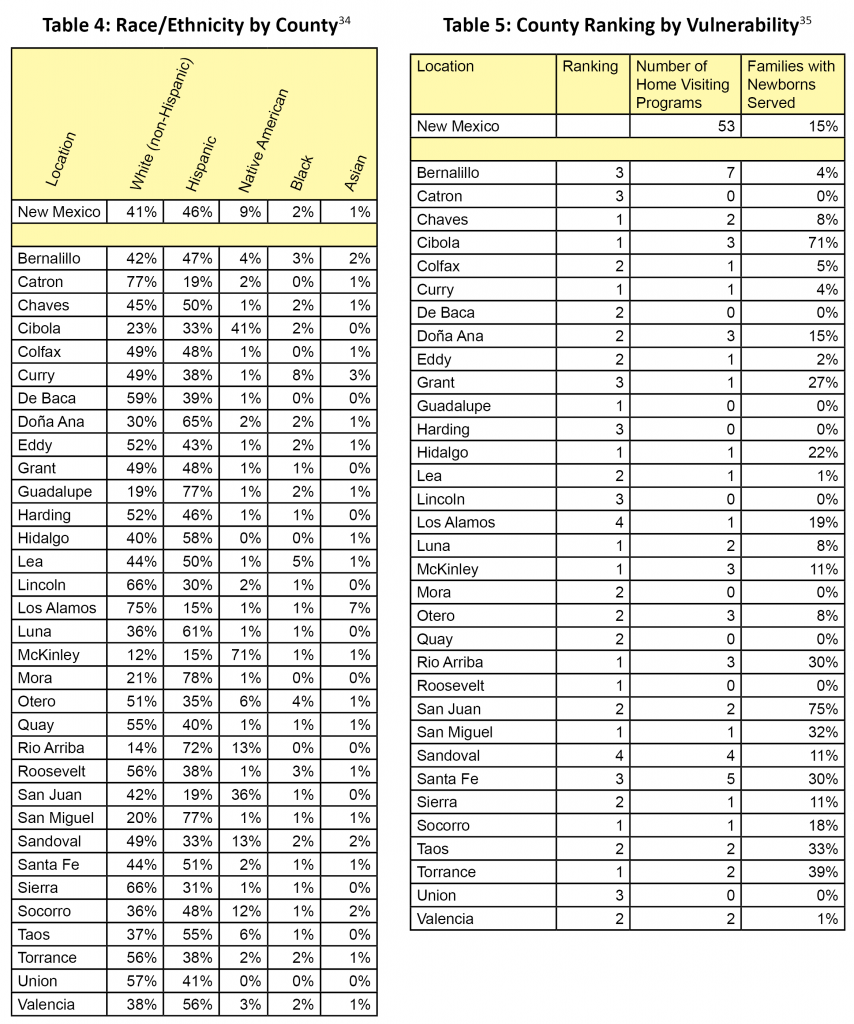

Nine out of the 12 counties listed as being most vulnerable in child-raising capacity have greater numbers of Hispanics and/or Native Americans than of other races or ethnicities. These include Chaves, Cibola, Guadalupe, Hidalgo, Luna, McKinley, Rio Arriba, San Miguel and Socorro. (See Table 4). “Minority” populations face greater disparities and challenges. Due to this, they (especially children) often suffer worse economic, health, education and other outcomes, a factor that should be brought into any consideration of priorities in terms of where to add home visiting programs to overcome “place”-related child-raising vulnerabilities in New Mexico.

Table 5 shows that in the counties with the most vulnerability/least capacity to best raise healthy children, five (Chaves, Curry, Guadalupe, Luna, McKinley, and Roosevelt) have the capacity to provide home visiting to few families, ranging from zero to 11 percent served. Roosevelt and Guadalupe counties (both with sizeable Hispanic populations) have no home visiting programs at all. McKinley County, in which seven out of every 10 families are Native American, only serves 11 percent of newborns.

Conclusion

More extensive, high-quality home visiting programs—as part of a comprehensive ECE system—can contribute greatly to improving education, health, and economic outcomes of New Mexico’s children. These programs do so by helping families—especially low-income, first-time families—deal with many of the barriers to child well-being faced at the earliest stages of a child’s life, especially in areas with fewer resources and support systems.

Things that can help the state get a higher rate of return on investment in these programs include:

- Use cost-benefit, effectiveness, demographic, and cultural data, along with knowledge of relevant funding streams (including Medicaid, public health, early childhood resources and education supports, such as the NM Land Grant Permanent Fund), to decide how to best allocate funding for home visiting and to develop a feasible plan for expansion and improvement in different areas. Take into account the sustainability of funding for these programs as well as the capacity of communities to undertake such programs.

- Invest in the development and retention of a skilled early childhood workforce that includes home visitors, and provide appropriate salaries and support systems.29

- Require that most home visiting funds be spent on implementing well-researched programs showing evidence of effectiveness. (The results of a rigorous evaluation being done by the Rand Corporation of the First Born® Program, a New Mexico home visiting model designed to meet the specific needs of the state’s families, will be of interest).

- Keep home visiting programs universal in nature, but set clear eligibility guidelines and compliance monitoring to assure more disadvantaged families (usually the least likely to receive services) have access to these programs.

- Require publicly-funded home visiting programs to track and document use of all funds, and to evaluate their performance and outcomes—but give them the resources to do this. This will help policy-makers make budget decisions and agencies manage resources, and help improve the quality and delivery of services.30

Endnotes

1. New Mexico Children, Youth and Family Department. (2010). Affordable Care Act Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program: New Mexico’s Statewide Needs Assessment, p. 2. Retrieved July 5, 2011 from http://www.cyfd.org/pdf/NM_HV_Needs_Assessment.pdf.

2. Op. cit., p. 15.

3. Pew Center on the States. (August 2011). States and the New Federal Home Visiting Initiative: An Assessment from the Starting Line. Philadelphia, PA: The Pew Charitable Trusts.

4. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. (October 3, 2003). “First reports evaluating the effectiveness of strategies for preventing violence: early childhood home visitation.” MMWR, 52 (RR14), 1-9. Retrieved July 19, 2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5214a1.htm.

5. Magnuson, K., Yoshikawa, H. & Brooks-Gunn, J. (June, 2008). What Research Tells Us About Program Effectiveness in the First Five Years. Presentation at the National Symposium on Early Childhood Science and Policy, Harvard University. Retrieved September 1, 2011 from http://developingchild.harvard.edu/index.php/download_file/-/view/109/.

6. Shonkoff, J. (2011). “Protecting brains, not simply stimulating minds.” Science, 333, 982-983.

7. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. (October 3, 2003). “First reports evaluating the effectiveness of strategies for preventing violence: early childhood home visitation.” MMWR, 52 (RR14), 1-9. Retrieved July 19, 2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5214a1.htm.

8. Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2011). Building the Brain’s “Air Traffic Control” system: how early experiences shape the development of executive function: Working Paper No. 11. Retrieved August 31, 2011 from http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

9. Higgins, L., Stagman, S. & Smith, S. (September 2010). Improving Supports for Parents of Young Children: State-level Initiatives. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty.

10. Howard, K. and Brooks-Gunn, J. (2009). “The role of home-visiting programs in preventing child abuse and neglect.” The Future of Children: Preventing Child Maltreatment, 19 (2), 119-146.

11. Pew Center on the States. (August 2011). States and the New Federal Home Visiting Initiative: An Assessment from the Starting Line. Philadelphia, PA: The Pew Charitable Trusts.

12. Karoly, L., Kilburn, M.R., and Cannon, J. (2005). Early Childhood Interventions: Proven Results, Future Promise. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

13. Rodriguez, M., Dumont, K., Mitchell-Herzfeld, M., Walden, N. & Greene, R. (2009). “Effects of Healthy Families New York on the promotion of maternal parenting competencies and the prevention of harsh parenting.” Child Abuse & Neglect, The International Journal, 34, 711-723

14. Karoly, L., Kilburn, M.R., and Cannon, J. (2005). Early Childhood Interventions: Proven Results, Future Promise. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

15. Margolis, P., Stevens, R., Bordley, W.C., Stuart, J., Harlan, C., Keyes-Elstein, L. & Wisseh, S. (2001). “From concept to application: the impact of a community-wide intervention to improve the delivery of preventive services to children.” Pediatrics, 108 (3), 1-10

16. Eckenrode, J., Campa, M., Luckey, D., Henderson, C., Cole, R., Kitzman, H., Anson, E., Sidora-Arcoleo, K., Powers, J. & Olds, D. (2010). “Long-term effects of prenatal and infancy nurse home visitation on the life course of youths.” Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 164 (1), 9-16.

17. Howard, K. and Brooks-Gunn, J. (2009). “The role of home-visiting programs in preventing child abuse and neglect.” The Future of Children: Preventing Child Maltreatment, 19 (2), 119-146.

18. Partnership for America’s Economic Success. (January 2011). Paying Later: The High Costs of Failing to Invest in Young Children Issue Brief. The Pew Center on the States. Retrieved October 2011 from www.pewcenteronthestates.org

19. Olds, D., Henderson, C., Cole, R., Eckenrode, J., Kitzman, H., Luckey, D., Pettitt, L., Sidora, K, Morris, P. & Powers, J. (1998). “Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children’s criminal and antisocial behavior; 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial.” JAMA, 280 (14), 1238-1244

20. Schuyler Center for Analysis and Advocacy. (Summer 2011). Home Visiting Saves Money, Prevents Child Abuse, Helps Children Learn and Strengthens Families. Albany, NY: SCAA.

21. De la Rosa, I., Perry, J., Dalton, L. & Johnson, V. (2005). “Strengthening families with first-born children: exploratory story of the outcomes of a home visiting intervention.” Research on Social Work Practice, 15 (5), 323-338.

22. National Forum on Early Childhood Program Evaluation. (2008). Evaluation Science Brief: Do Nurse Home-Visiting Programs have Lasting Benefits for Mothers and Children? Retrieved August 12, 2011 from http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

23. Anonymous. (2005). Proven Benefits of Early Childhood Interventions. Labor and Population Research Brief. Santa Monica, CA: The Rand Corporation.

24. Mitchell, J. (July 2011). Central New Mexico Education Needs Assessment. Albuquerque, NM: United Way of Central New Mexico.

25. Karoly, L., Kilburn, M.R., and Cannon, J. (2005). Early Childhood Interventions: Proven Results, Future Promise. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

26. Magnuson, K., Yoshikawa, H. & Brooks-Gunn, J. (June, 2008). What Research Tells Us About Program Effectiveness in the First Five Years. Presentation at the National Symposium on Early Childhood Science and Policy, Harvard University. Retrieved September 1, 2011 from http://developingchild.harvard.edu/index.php/download_file/-/view/109/.

27. New Mexico Legislative Hearing Brief. Early Childhood Services (CYFD, DOH, PED). Code 690,665,924. August 17, 2011.

28. Bruner, C., Stover Wright, M., Tirmizi, S.N. and the School Readiness, Culture, and Language Working Group of the Annie E. Casey Foundation. (January 2007). Village Building and School Readiness: Closing Opportunity Gaps in a Diverse Society. A Resource Brief of the State Early Childhood Policy Technical Assistance Network. Des Moines, IA: Child and Family Policy Center.

29. Magnuson, K., Yoshikawa, H. & Brooks-Gunn, J. (June, 2008). What Research Tells Us About Program Effectiveness in the First Five Years. Presentation at the National Symposium on Early Childhood Science and Policy, Harvard University. Retrieved September 1, 2011 from http://developingchild.harvard.edu/index.php/download_file/-/view/109/.

30. Pew Center on the States. (August 2011). States and the New Federal Home Visiting Initiative: An Assessment from the Starting Line. Philadelphia, PA: The Pew Charitable Trusts.

31. Bruner, C., Stover Wright, M., Tirmizi, S.N. and the School Readiness, Culture, and Language Working Group of the Annie E. Casey Foundation. (January 2007). Village Building and School Readiness: Closing Opportunity Gaps in a Diverse Society. A Resource Brief of the State Early Childhood Policy Technical Assistance Network. Des Moines, IA: Child and Family Policy Center.

32. Bruner, C. (August 2010). Learning to Read: Developing 0-8 Information Systems to Improve Third Grade Reading Proficiency. Des Moines, IA: Child and Family Policy Center.

33. Data for Table 2 come from the U.S. Census, American Community Survey, 2005-2009. Tables (in order of columns, left to right): B11004, B17010, B11012, B19054, B19057, B19052, B16004, B15002, B15002, and B14005.

34. Data for Table 4 come from the U.S. Census, American Community Survey, 2009.

35. Data for columns 2 (Number of Home Visiting Programs) and 3 (Families with Newborns Served) come from the 2010 New Mexico Home Visiting Statewide Needs Assessment report and supporting data tables from the NM Department of Health.

Download this report (Dec. 2011; 8 pages; pdf)

Find more data for New Mexico and the nation on the KIDS COUNT Data Center

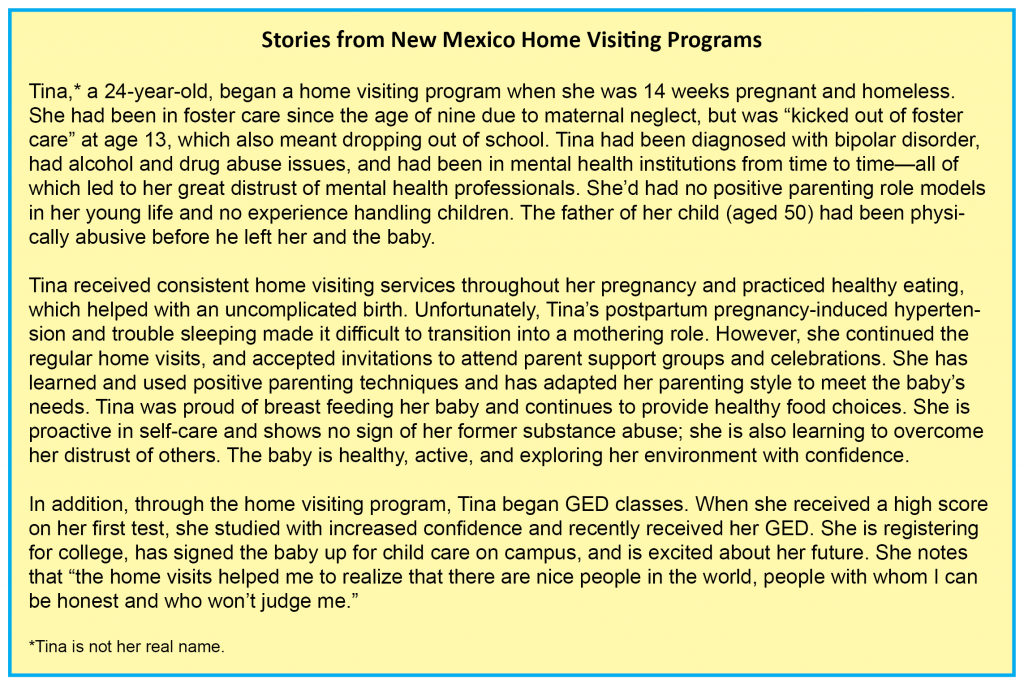

New Mexico KIDS COUNT wishes to thank a variety of home visiting programs around the state for providing stories and examples of how effective home visiting can be for their clients. We have tried to ensure anonymity through the use of false names and by leaving out geographic or other potentially identifying information. We appreciate their assistance with this report.

NM KIDS COUNT is a program of the Annie E. Casey Foundation.