Download the full report with all the data (64 pages; Jan. 2013; pdf)

Find more data for New Mexico and the nation on the KIDS COUNT Data Center

Introduction: A Profile of the Well-Being of Our State’s Children

Introduction: A Profile of the Well-Being of Our State’s Children

New Mexico Voices for Children is pleased to present the 2012 New Mexico KIDS COUNT Data Book. This report provides the most up-to-date, reliable data that show how New Mexico children and their families fare economically, academically, socially, and with regard to their health. This is the 20th year in which we have published the annual KIDS COUNT Data Book. Our intent is to provide decision-makers at the state, tribal, and local levels with the information they need to promote and support children’s interests and family economic security.

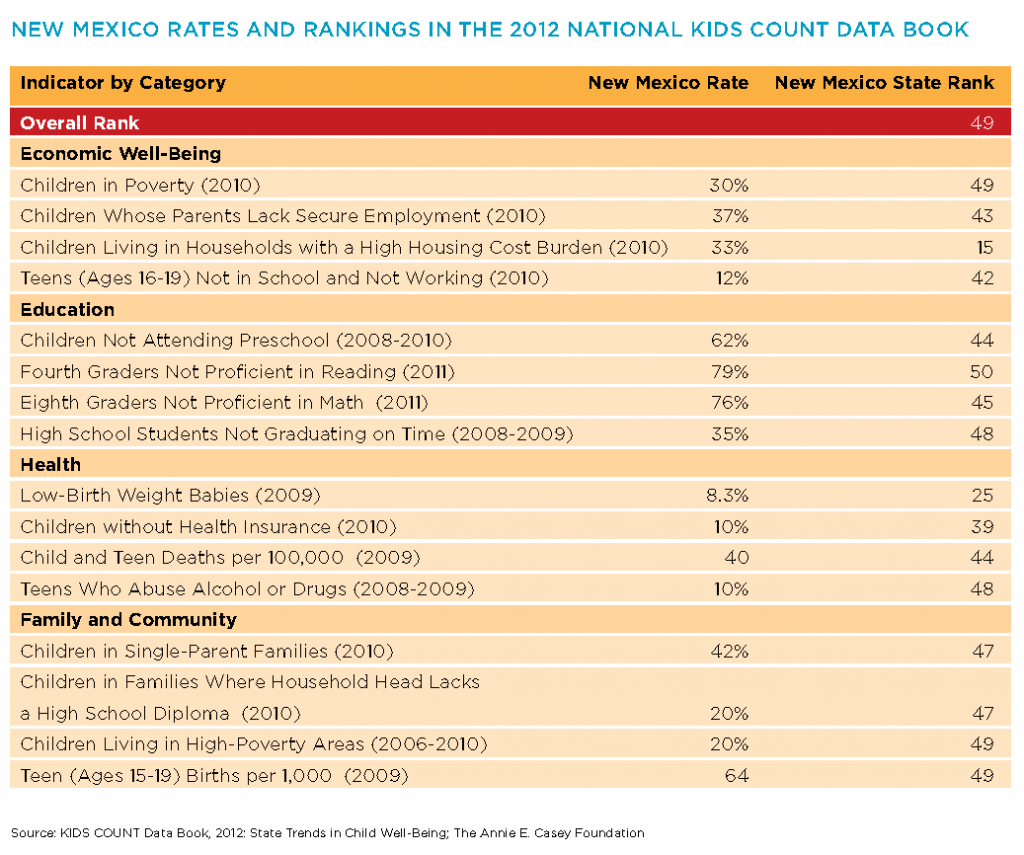

Every year the Annie E. Casey Foundation releases the national KIDS COUNT data book. New Mexico has not fared well when ranked against the other 49 states. Every year for the last two decades, New Mexico has ranked in the bottom ten—and often in the bottom five—of states with regard to child well-being. In 2012, the national KIDS COUNT program revised its respected indicators of child well-being in order to provide a more complete picture of child well-being. This comprehensive index is organized into four domains and uses indicators that very accurately predict children’s future success. In general, our state’s status has not improved with the use of these revised indicators. The 16 indicators are listed at right, with New Mexico’s statistics and ranking among the 50 states:

Summary and Meaning of New Mexico’s Data

Demographics: New Mexico’s population now stands at over two million, and more than a quarter (28 percent) of our population is under the age of 20. The most populous counties are Bernalillo, Doña Ana, Santa Fe, Sandoval, and San Juan. The state continues to maintain its majority-minority status, with 46 percent of the population being Hispanic, 41 percent non-Hispanic white, 9 percent Native American, and 6 percent African-American, Asian, or mixed/other race. Counties in which Hispanics make up the largest share of the population include Mora, San Miguel, Guadalupe, Rio Arriba, Doña Ana, and Luna. McKinley, Cibola, and San Juan counties have majority Native American populations. Among children and youth ages 0 to 19, the racial/ethnic breakdown also reflects the majority-minority status: 48 percent are Hispanic, 23 percent are non-Hispanic white, 10 percent are Native American, and 19 percent are African-American, Asian, or mixed/other race.

Family and Community: The number of children living in single-parent households in New Mexico is a troubling indicator. Family structure is swiftly changing. At the national level, the percent of children living with married parents dropped steadily from the 1970s to the early 2000s, when it held steady, then dropped again by 2010.1 In New Mexico, approximately 42 percent of children now live with single parents and 29 percent of families are headed by single mothers.

More than half of the children in four counties—Cibola (62 percent), McKinley (56 percent), San Miguel (54 percent), and Rio Arriba (53 percent)—live in families headed by single mothers. In three of these counties—McKinley, Cibola, and Rio Arriba—the birth rates for single mothers are also higher than the state rate (7 births per 1000 women). Research shows that single-parent families tend to have lower incomes and assets, and that children in these families are at greater risk for behavioral and health problems, as well as for lower educational attainment. As New Mexico’s economy slowly recovers from the recession, single-parent families will need support to weather this lengthy period of economic strain.

The term “place” refers to where people live, play, work, go to school, and interact with others and, as such, place has a great impact on children’s health, well-being, and future. Unfortunately, fully one fifth of New Mexico’s children live in areas of concentrated poverty. (Places of concentrated poverty are areas in which 30 percent of the population lives in poverty and where community resources are scarce or of low-quality.) Only one other state has a lower ranking than New Mexico on this important measure. It is alarming that in four counties—McKinley (67 percent), Luna (62 percent), Curry (45 percent), and Doña Ana (44 percent)—the rates of children living in high-poverty areas are even higher than that of the state as a whole.

Studies from around the world show the importance of parents’ (especially mothers’), level of educational attainment to the future well-being of their children. In general, the higher the educational attainment of parents, the better a child will do in life. It is disconcerting to note, therefore, that New Mexico ranks very low, 47th among the states, with a proportion of its children (20 percent) living in families in which the household head lacks a high school diploma. In addition, 36 percent of the state’s families that live in poverty are headed by a non-high school graduate. Noting again the importance of “place” in children’s development, few children in New Mexico are growing up in places where many adults—potential role models—have a bachelor’s degree or higher. New Mexico’s adults, age 25 and above, have fairly low levels of educational attainment; only 11 percent have a graduate-level degree, and only 15 percent have a bachelor’s degree. It is also disturbing that so many students—up to 28 percent in some counties—enroll in college but never graduate.

Education: Education is a key ingredient in today’s recipe for social and economic success in the 21st century. Regrettably, too many of New Mexico’s children, from the earliest years, are on the wrong trajectory in terms of realizing academic and economic success. Extensive scientific, educational, and economic research has shown that it is in the earliest years of life, from birth to age 5, that the most important and extensive brain development takes place. Early learning experiences during this time mold the neurological circuitry and architecture of the maturing brain. These experiences, including interactions with parents and other adults, build either a sturdy or fragile foundation for a child’s cognitive, emotional, social, and behavioral capacity.

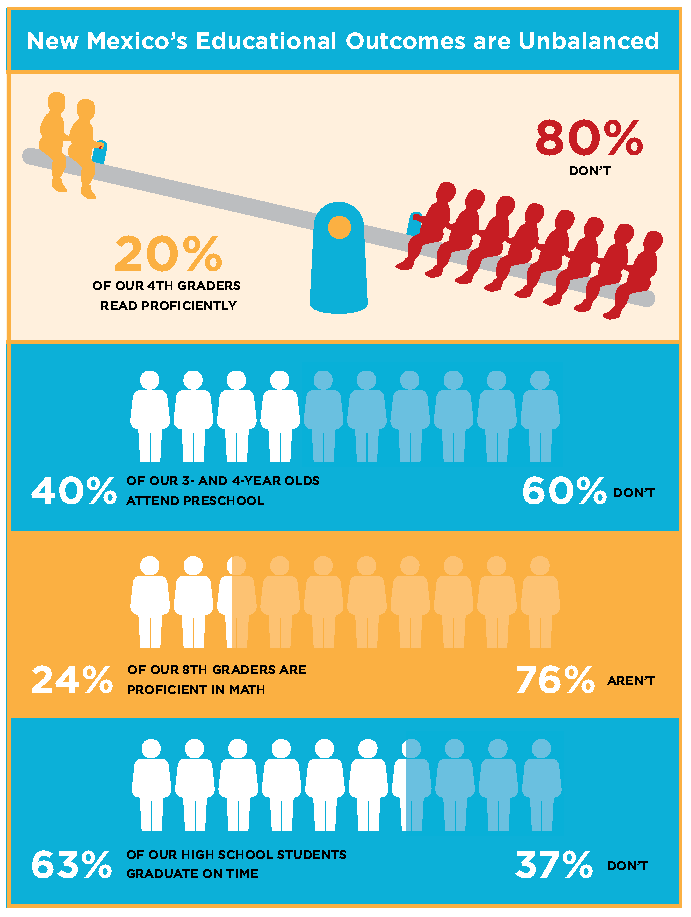

High-quality early childhood care and education (ECE) include services like pre-natal care, home visiting/parent mentoring, licensed child care (including child care assistance for low-income parents), and high-quality preschool programs. These services are essential to the positive learning and brain development of our infants and toddlers, and preschool can help prepare them to do better in grades K-12. But only about 40 percent—less than half—of New Mexico’s 3- and 4-year-olds are enrolled in preschool programs. In some counties, notably Valencia, only about one in four children attend preschool. Besides access, however, the quality of preschool (and other ECE programs) is also very important but quite often lacking. In Luna County, for example, which has one of the best preschool enrollment rates (64 percent), school administrators still note that too many of their new kindergarten students are not prepared for school when they start.2

Significant evidence exists showing that children’s participation in high-quality, comprehensive ECE programs helps lead to improved academic progress and performance. In New Mexico, where most children do not attend preschool, the consequences can be seen as early as 3rd grade in reading proficiency scores. (Reading proficiency by 4th grade is considered a “make-or-break benchmark” for whether a child will succeed in school and in life. This is because children “learn how to read” through 3rd grade. In 4th grade and beyond, they must “read to learn,” i.e. use their reading skills to learn other subjects like math and science.3) A student who is not proficient in reading by 4th grade may find subsequent educational content extremely difficult to read. This leads to frustration as these children fall behind other students in school performance. Such students often face potential grade retention, and may develop social and behavioral problems. Children who are not proficient readers by 4th grade are more likely to drop out and/or not graduate from high school.4

The national KIDS COUNT Program, using the National Assessment for Educational Progress (NAEP), a standardized test that allows comparability of reading scores across states, ranks New Mexico 50th—dead last—among the states in 4th grade reading proficiency. Only about 20 percent—just two out of every ten New Mexico 4th graders—can read at a proficient level. If we consider the results from New Mexico’s own 3rd grade reading proficiency test, the results are not any more encouraging. While in six school districts as many as 70 percent to 80 percent of 3rd graders score at a “proficient and above” level, in too many others—more than one-third of our public school districts—only 50 percent or less of the 3rd graders read proficiently or above. This does not bode well for many students’ potential to succeed as they progress into higher grade levels. This concern seems justified when we consider the low math proficiency rates of New Mexico’s 8th graders. In only 11 out of the state’s 89 public school districts do 60 percent or more of the 8th graders score at a “proficient or above” level. In two-thirds (60) of the school districts less than half the students can do math at the required level. Given that skill in mathematics is considered vital for 21st century technical jobs, low proficiency in mathematics is alarming in its implications for New Mexico’s future workforce capacity.

These low proficiency scores have an effect on the state’s high school graduation rate. A 2012 report from the U.S. Department of Education ranked only one state lower than New Mexico in terms of the on-time high school graduation rate.5 The state’s graduation rate, 63 percent (only 56 percent for economically disadvantaged students), means that more than one-third (37 percent) of our youth do not graduate from high school within four years. There are better performance rates, however. Some public school districts—most of them in small communities—have graduation rates of 90 percent and above.

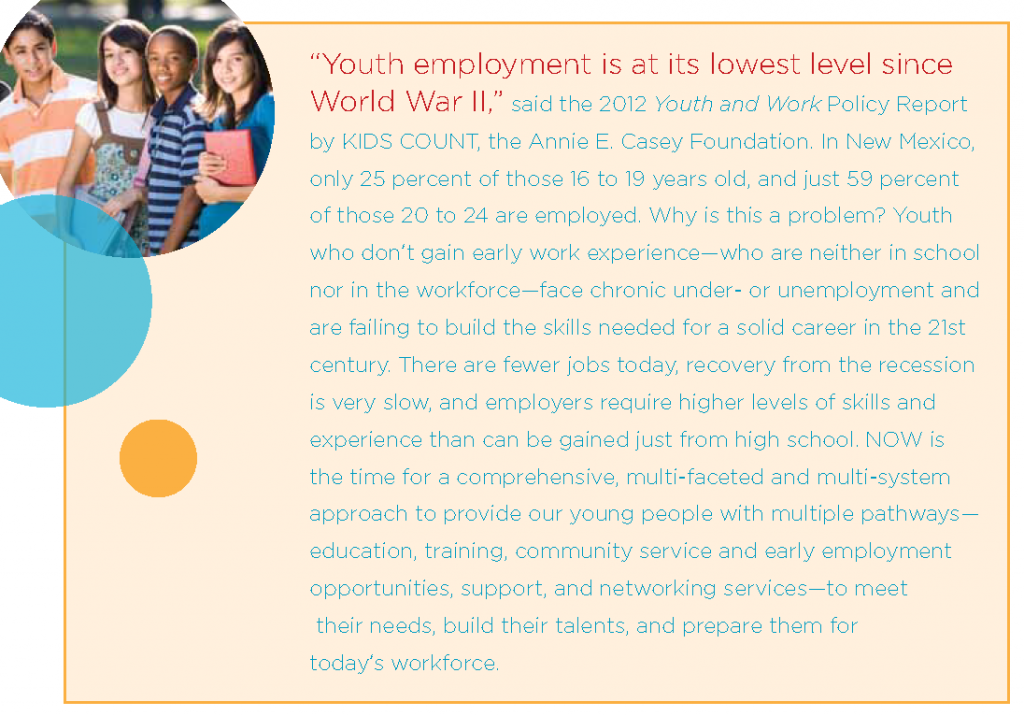

Economic Well-Being: Many of these educational indicators appear to contribute to the high proportion of New Mexico teens, ages 16 to 19, who are not in school and not working. Roughly 12 percent of these teens, often referred to as “disconnected” youth, are missing out on either early work experiences or higher education that will provide them with the pathways to more highly-paid careers, and/or protect them from chronic unemployment. In New Mexico, teens in this age group who do not have a high school diploma are more likely to fall into this “disconnected” youth category.

New Mexico families, especially those with children, are still struggling with the aftermath of the recession and the slow economic recovery. Always considered one of the “poor” states in the nation, New Mexico’s median household income, at $43,715, is more than $7,000 less than the national median. The number of families considered “middle class” is shrinking as families struggle to stay above poverty, provide adequate nutrition for their children, pay expensive medical costs, and hold onto homes and employment. Currently, New Mexico ranks 49th among the states in the percent of children living in poverty—close to one-third of our state’s children live below the poverty level. In some counties, the rate is even higher than that. In Luna County, more than half of the children under age 18 live in poverty, and two out of every five children in Taos County are poor. One indicator of poverty is that two-thirds of students in New Mexico schools are eligible for free and reduced-price lunch and breakfast. In some public school districts, 90 percent or more of the students are eligible for free or reduced-price meals.

A marker of how much the lingering recession impacts families is the fact that more than one-third (37 percent) of the state’s children live in families in which no parent has full-time, year-round employment. Counties with particularly high rates of families where parents lack secure employment include Grant and San Miguel (31 percent each), and Cibola and Rio Arriba (29 percent each). Another sign that families with children are under financial stress is the increased percentage of households receiving SNAP benefits (formerly known as “food stamps”).

The state’s rate of enrollment has grown from 11 percent to 13 percent (2008-2011), and in some counties, like Luna, as many as one in five families receives SNAP.

An additional measure of family economic security is the extent to which households have financial assets and resources—such as savings, interest from investments, and rental income—to help them weather a catastrophic financial event. These events can include the loss of a job, crushing medical debt, or even a recession. In this state, less than one in five households has these types of assets to fall back on. A greater percent of families with investment and rental income live in Santa Fe, Lincoln, and Grant counties, while less than one in ten households in Cibola, McKinley, and San Miguel counties has these resources.

In New Mexico, a large number of households also struggle with high housing costs; that is, they pay more than 30 percent of their income for rent or on a mortgage. Approximately 65 percent of New Mexico households are shouldering high housing costs, and one-third of the state’s children live in these households. This means that these families have less money to pay for food, clothing, utilities, and other essentials that ensure the health and well-being of their offspring.

Health: All of the factors described above have an impact on children’s physical and emotional health and well-being. One major means of promoting children’s health—one that is keenly influenced by policy decisions—is health insurance coverage for young people, especially those living in poor and low-income families. With insurance coverage, children are more likely to get the preventive visits, immunizations, developmental checks, and care needed to keep them on a positive trajectory of physical, intellectual, and emotional growth. In New Mexico, approximately 14 percent of children under age 18 do not have health insurance of any kind, and of the 86 percent of children who do have insurance, 46 percent are covered by Medicaid.6 Over half (52 percent) of New Mexico’s children under age 19 are living in poverty-level and low-income families.7 It is clear that Medicaid, which covers about 337,000 kids under age 21, is of crucial importance to the health of our youth. Medicaid must be sustained and all eligible children enrolled.

Other KIDS COUNT indicators that highlight the health status of New Mexico adolescents show that there is room for concern: New Mexico ranks 48th among the states in the proportion of teens who abuse alcohol and drugs. According to data from the state’s Department of Health and the Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey, one in four of the state’s high school students use illicit drugs and/or engages in binge drinking. (Binge drinking is defined by the YRRS as having five or more drinks of alcohol in a row, within a couple of hours, on one or more of the past 30 days.) In some of our state’s counties the rates of teens reporting they binge drink are even more alarming: 42 percent in Union County; 38 percent in Santa Fe and Mora counties; and 37 percent in Sierra and Taos counties. Alcohol and drug use may also be factors in the high teen death rates in the state—59 per 100,000 teens.

In addition, New Mexico continues to have the second highest rate of teen (ages 15-19) births, especially among Hispanics and Native Americans. Although the state’s teen birth rate appears to be slowly decreasing, we continue to have higher rates than most other states. Children born to teens are at much greater risk of being trapped in the cycle of family poverty, having poor educational achievement, engaging in criminal behavior, and becoming teen parents themselves.

Taking Action

New Mexico does not have comprehensive policies that provide all children in our state access to the opportunities that promote progress and allow youth to reach their full potential. The research exists that can guide us to develop and implement policies that promote and support children and families, from (and before) birth through adolescence. New Mexico needs to move from knowledge to practice.

State government should support and fund a comprehensive, high-quality early childhood care and education system of services. These services include prenatal care and home visiting programs, high-quality child care, and preschool. Such programs will do much to improve the well-being of New Mexico’s children, giving infants and toddlers the best start during the most critical developmental stage of their lives and ensuring that children are reading by third grade and will have the necessary foundation for a successful path to high school graduation and college/career readiness. We also need to provide greater access to education and training opportunities to adults in our communities. We know that the increased educational attainment levels of the adults (parents) in our state will result in improved educational outcomes for our children. We must also ensure that children and families have adequate access to health care and insurance. Providing funding that supports child and youth development across education, health, workforce development, and other systems is needed. Policymakers should require accountability by linking program funding to meaningful outcomes and continue or eliminate programs based on their effectiveness.

State and local policymakers need to make use of credible data in considering the potential impact of budgetary and policy decisions. The data and information on the current status of child and family well-being provided in this 2012 New Mexico KIDS COUNT Data Book are meant to be of use to decision-makers in taking meaningful steps to address and reduce the adverse economic, social, and educational factors impeding our children’s prospects for future success.

Endnotes

1. Child Trends/Data Bank (Family Structure)

2. Personal conversations with participants in a Connecting Data to Action workshop in Deming, NM, and other meetings held in Luna County with the NM KIDS COUNT director in 2011 and 2012

3. Fiester, L. & Smith, R. (2010). Learning to Read—Early Warning! Why Reading by the End of Third Grade Matters: A KIDS COUNT Special Report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Baltimore, MD: Annie E. Casey Foundation

4. Ibid

5. U.S. Department of Education. (2012). Provisional Data File: SY2010-11 Four-Year Regulatory Adjusted Cohort Graduation Rates

6. U.S. Census, Current Population Survey. (2010). Table H105

7. U.S. Census, Current Population Survey; 2011 Annual Social and Economic Supplement. (2010). Table HI10

KIDS COUNT is a program of the Annie E. Casey Foundation.