Download this report (May 2014; 12 pages; pdf)

Link to the press release

by Gerry Bradley, M.A.

Two lawsuits filed in March and April of 2014 against the state Public Education Department are calling into question the sufficiency of public school funding for educating New Mexico’s nearly 340,000 school-age children. From a performance perspective, it is hard to argue that New Mexico has provided the resources necessary for children to thrive, as too many students are not reaching benchmarks in reading and math proficiency. Clearly, the recession made it challenging for legislators to fund our public school system but recent policy choices have exacerbated the problem.

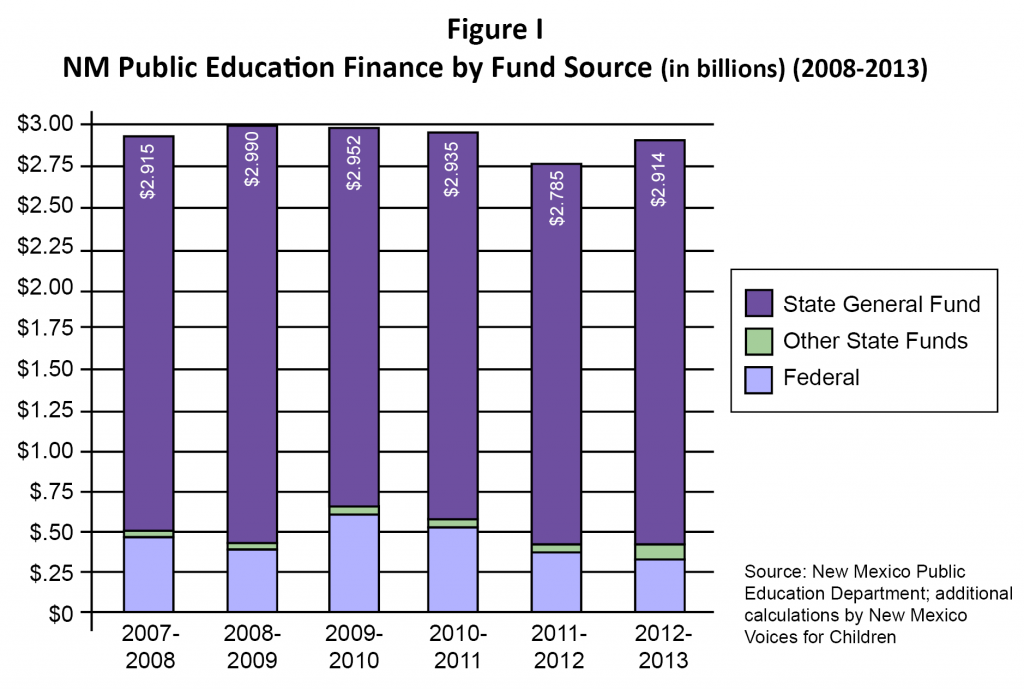

Public school funding in New Mexico rose steadily from 1983 to 2008. But a study1 conducted in 2008 determined that the state was still severely under-funding K-12 education based on requirements in the state constitution. Before this shortfall was addressed, however, the recession sent New Mexico’s revenue plummeting. Rather than replace lost revenue by raising taxes, New Mexico policy makers addressed the revenue crisis by slashing state spending in many areas, including public schools. Like other states, New Mexico was able to temporarily plug some of its budget holes with federal revenues from the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). The availability of federal ARRA funds in the 2009-10 and 2010-11 school years lessened the overall cuts in New Mexico, as shown in Figure I.

New Mexico’s recovery from the recession has been slow. State revenues began to recover in 2012 and spending on public education was increased. Unfortunately, much of the new revenue was also spent on tax breaks for profitable corporations already doing business in New Mexico. While the stated objective of the cuts was to lure other companies here, there is no evidence that this will be the result. Investing more of that new revenue into the public K-12 school system would have been a smarter economic development decision, as businesses do not need tax breaks in order to operate but they do need an educated workforce.

This report shows that choices regarding taxes and spending have consequences. Specifically, we show that public school funding has not kept pace with inflation and enrollment growth. That is, per-pupil, inflation-adjusted funding for school operations has dropped by more than 14 percent since 2007-08. We must do better for the future of New Mexico’s children and economy.

A Vulnerable Population

There are important reasons New Mexico needs to increase investment in K-12. Our state has one of the highest rates of child poverty in the nation. Almost one-third of our children live at or below the federal poverty line (which is just over $19,000 for a family of three). Children who come from low-income families need more social supports than do children from middle- and upper-income families. Because they often lack opportunities, low-income children are less likely to start kindergarten with the basic skills that are necessary for them to succeed in school.

Low-income students also are at greater risk of falling behind during the summer months. Children from high-income households can afford enriching summer activities—such as attending summer camps, visiting museums, and traveling—which not only stem the learning loss that can occur over the summer, but can actually improve overall academic achievement. Children from low-income households are much more likely to need basic remediation at the start of each school year.

School achievement gaps fall along racial and ethnic lines as well as economic lines as minority children face greater barriers to success than their White counterparts. Almost three-quarters of New Mexico’s children are members of a racial or ethnic minority group. Only one other state—Hawaii—has a lower percentage of White children than does New Mexico. These issues need to be kept at the forefront when state leaders are making public school funding decisions.

The Funding Formula

One strength of New Mexico’s public school finance system is that it is quite centralized, in that most of the funding comes from state rather than local sources. Most states rely heavily on the property tax to pay for the operation of their schools, while New Mexico relies on revenue collected at the state level. Since property tax revenue varies greatly from high-income to low-income neighborhoods, a funding system that relies on the property tax tends to favor schools in well-to-do areas.

New Mexico uses the State Equalization Guarantee (SEG)—commonly referred to as the ‘funding formula’—as the mechanism for distributing funds to its 89 school districts. The SEG is the amount allocated to each district by the state Public Education Department (PED) for each unit value. (Unit value is not comparable to student enrollment because students needing more supports, such as special education, may count as more than one unit.) Only state funding and ‘above-the-line’ expenditures are included in the SEG. ‘Below-the-line’ funding pays for specific programs—such as pre-kindergarten, K-3 Plus, and teacher evaluations, supports, and training—which are not necessarily offered by all school districts and, therefore, are not included in the formula. We will look at all spending later in this report.

The spending as determined by the SEG increased smoothly for almost three decades—from 1983 to 2008—before dropping at the onset of the recession.

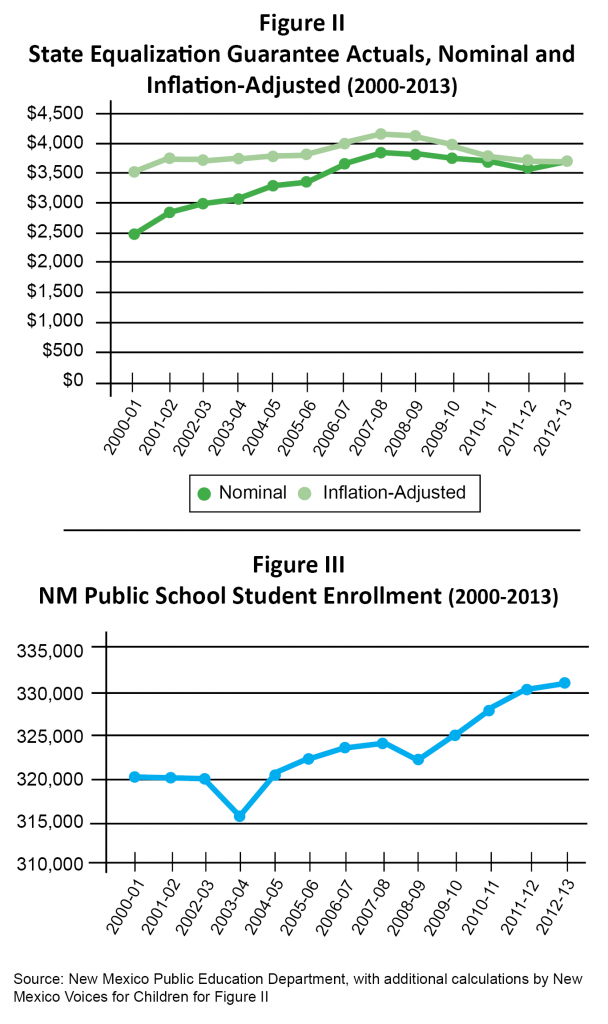

The dark green line in Figure II shows the formula from 2000 to 2013 in nominal dollars. The formula hit its peak in 2007-08 before beginning a steady decline. A slight increase is seen in 2012-13, but that is before adjusting for inflation.

The light green line provides a better picture of the current value of the SEG, which peaked at an inflation-adjusted $4,000 (in 2013 dollars) in 2008-09 just after the recession started to crush revenues in 2008-09. As the light green line indicates, after stabilizing in 2010-11 the SEG flattened when adjusted for inflation.

At the same time that the real value of K-12 revenue was decreasing, student enrollment in the state’s public schools was trending upward (Figure III). Not only was the SEG not keeping pace with inflation but, for the past decade, schools have been expected to educate more children without more money. Inevitably, this has resulted in a decline in per-pupil spending for New Mexico’s schools.

Funding for School Operations

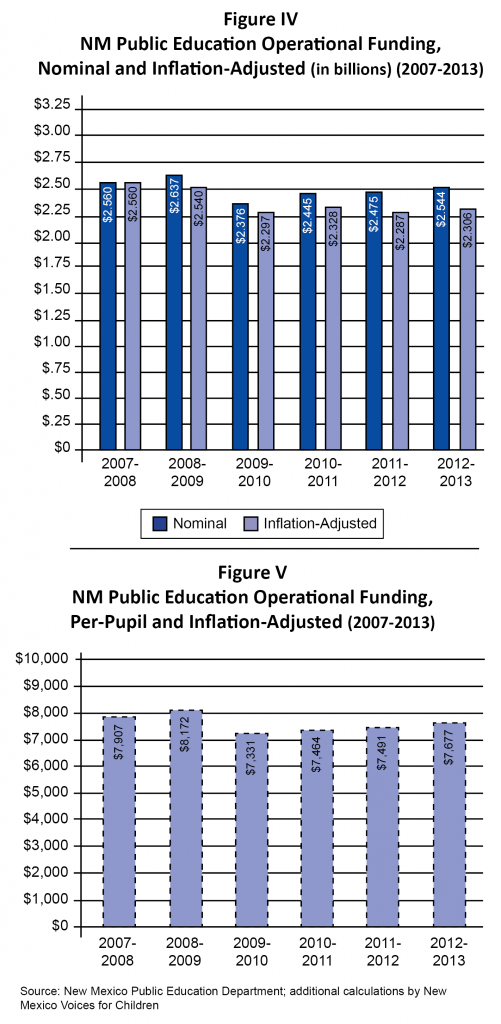

Broadly speaking, the revenues going into the public school system are broken into four uses: operational, special projects, capital outlay, and debt service. The funding going to each of these classifications varied in different ways during the past six years. For the first and largest classification—operational expenses (shown in Figure IV)—funding rose from $2.56 billion in the 2007-08 school year to $2.63 billion in the 2008-09 school year. The recession took its toll on New Mexico revenues and operational funding dropped to $2.37 billion in 2009-10.

Operational funding began a slow recovery in 2010-11 ($2.44 billion) and 2011-12 ($2.47 billion), reaching $2.54 billion in 2012-13 (the most recent year for which data are available). Operational appropriations, therefore, were still below pre-recession levels as late as 2012-13, both in nominal dollars (shown in the dark blue bars) and when adjusted for inflation (light blue bars).

Figure V shows operational appropriations on a per-pupil, inflation-adjusted basis.

Funding for Special Projects

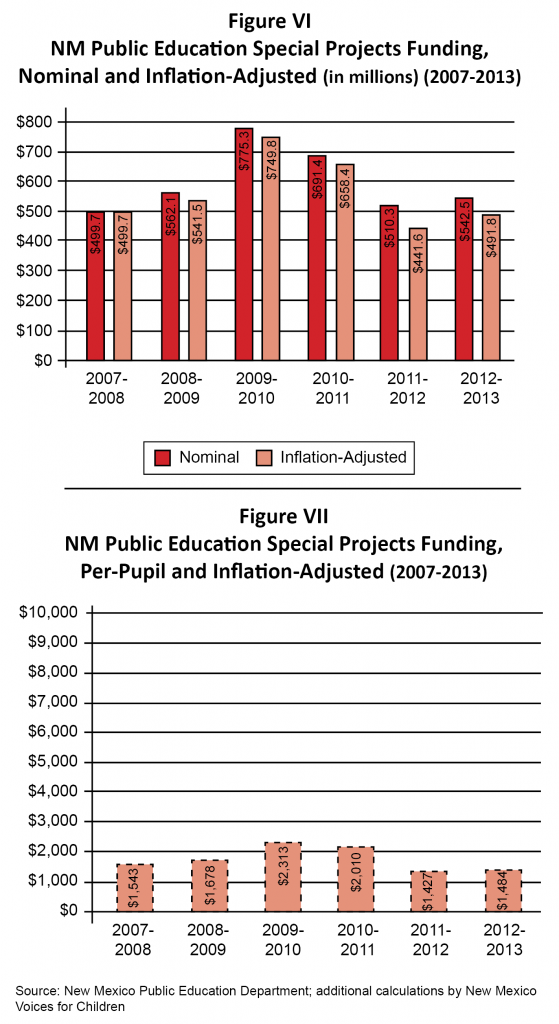

The special projects category includes a wide array of programs, from school lunches to extra funds for schools in high-poverty neighborhoods. Many of these are federally funded Title I programs. The impact of the federal ARRA revenues is especially clear in this category, since much of the ARRA funding arrived under the Title I category.

Figure VI shows that federal ARRA funding shot up in 2009-10. The intent of the ARRA was to prevent funding from dropping sharply due to the recession, especially for schools in high-poverty areas. Funding for special projects remained at an elevated level in 2010-11 at $691 million, before dropping by $180 million between 2010-11 and 2011-12 to pre-recession levels, then remaining flat into 2012-13.

Figure VII shows special projects revenues on a per-pupil, inflation-adjusted basis.

The Federal Infusion

Taking operational and special projects funding together—along with the infusion of federal ARRA money—there was still a drop of almost $50 million between 2008-09 and 2009-10. In New Mexico, funding for special projects went up by $213 million or almost 40 percent between 2008-09 and 2009-10. The increase in appropriations for special projects went some distance toward offsetting the drop of $261 million in operational appropriations. Operational funding began its slow ascent between 2009-10 and 2010-11, climbing by about $70 million, then barely budging between 2010-11 and 2011-12, rising by $30 million or just 1.2 percent.

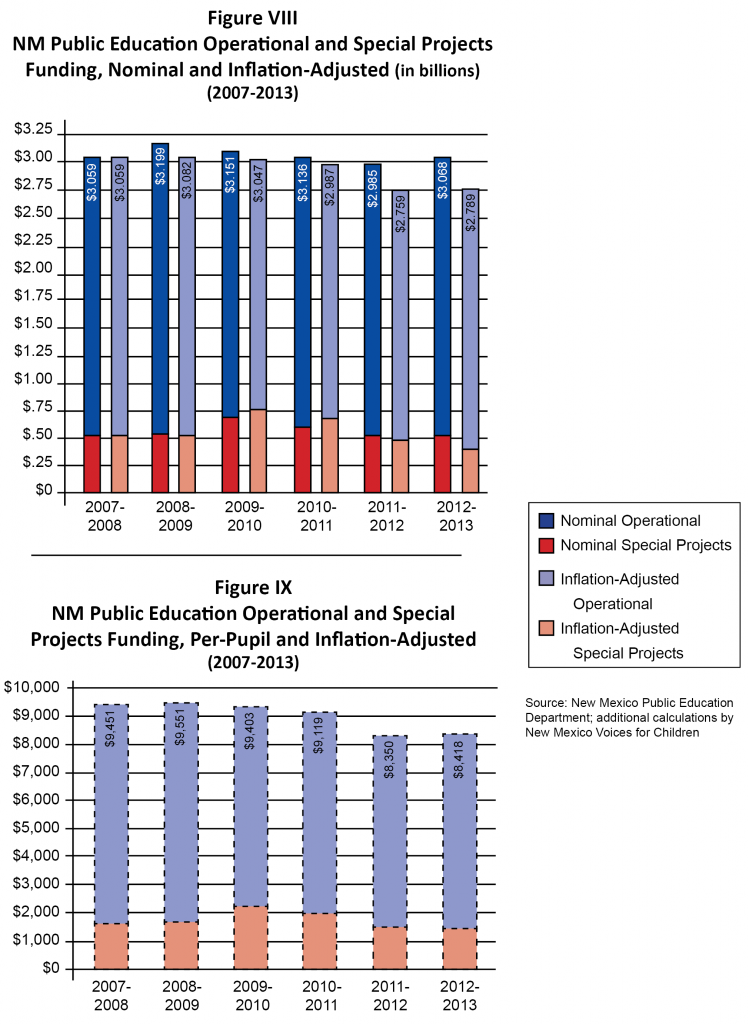

Taken together, operational and special projects revenues were $3.06 billion in 2007-08, $3.2 billion in 2008-09, and $3.08 billion in 2012-13—still lower than the 2009-10 level (see Figure VIII). Figure IX shows operational plus special projects revenues on a per-pupil, inflation-adjusted basis.

Funding for School Buildings

The remaining two revenue categories are related to capital outlay—the construction and upkeep of school buildings. Capital outlay money is generally borrowed via the bonding process. Debt service is money needed for payments on borrowing for capital projects. Since capital outlay is not part of the appropriations process, it is not discussed in detail in this report.

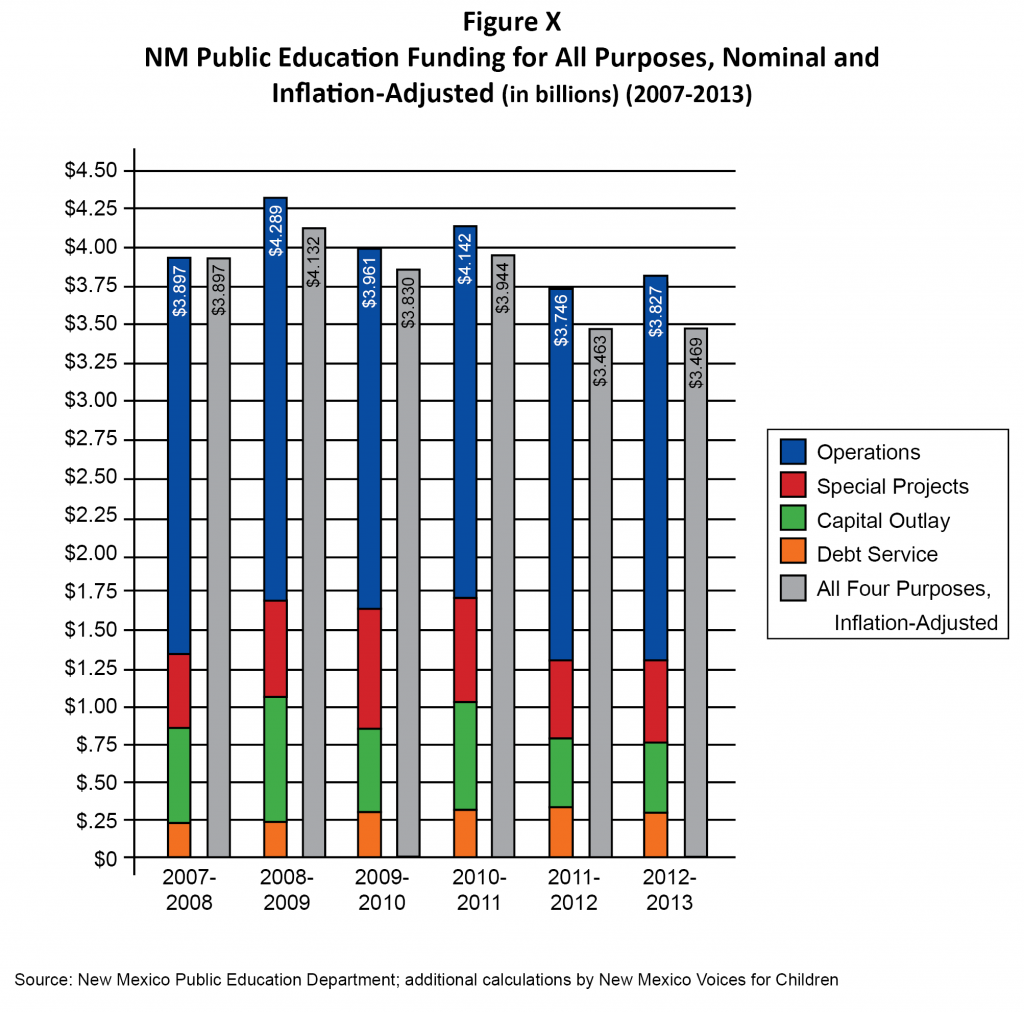

The total funding picture (Figure X) is more informative after having looked at appropriations by source. Taken together, appropriations peaked in 2008-09, fell slightly in 2009-10, before rising in 2011-12 and 2012-13. There are no clear trends for capital outlay and debt service, while operational revenues collapsed in 2009-10 and special projects revenues rose to compensate. Again, the increase in special projects was largely due to the infusion of federal ARRA funds through the Title I program.

Funding by Source

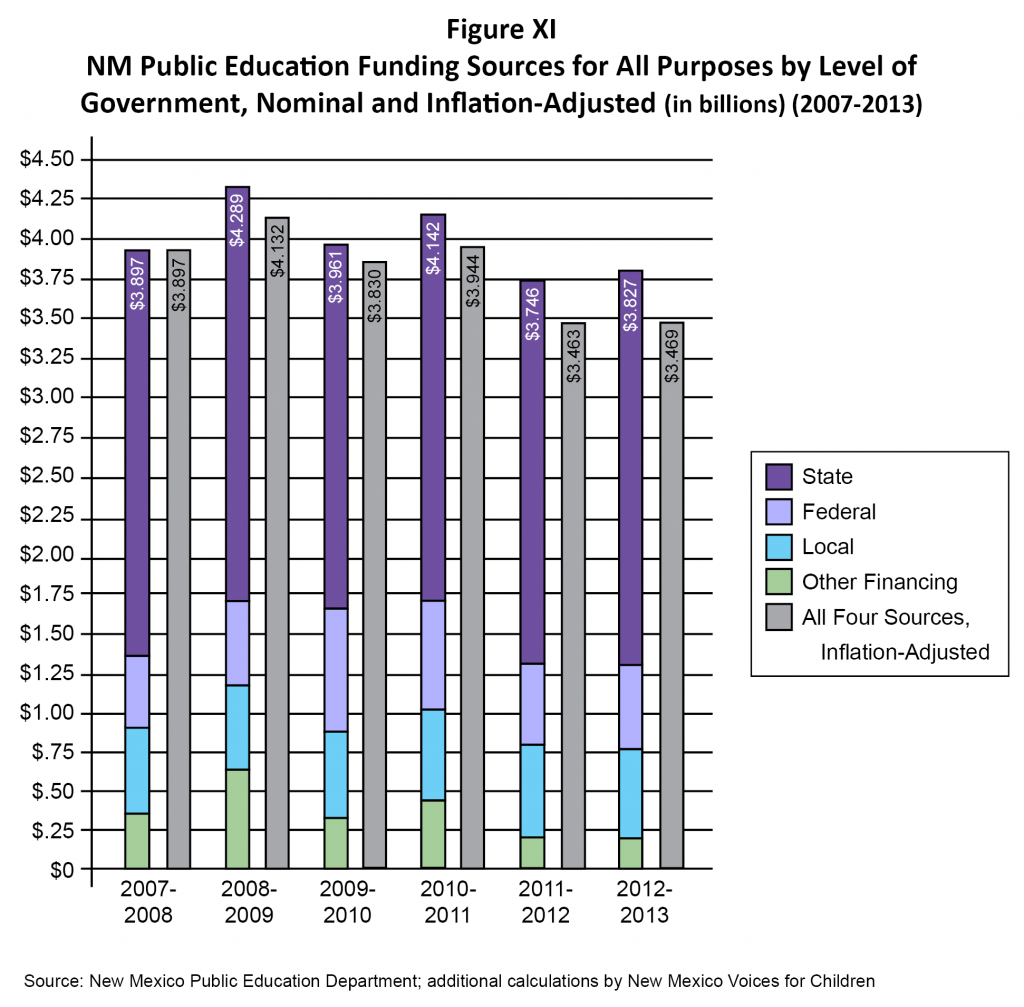

Figure XI shows public school funding from a different perspective—that of revenue sources by level of government. This perspective clarifies further the role of federal ARRA funds in stabilizing revenue for the New Mexico public school system.

The Operating Budget

The discussion so far has looked at public school funding from all sources. The operating budget is made up of just the money that is appropriated by the state Legislature during the annual legislative session. The operating budget includes above-the-line funding as well as below-the-line funding, which pays for programs that are not necessarily offered by all school districts. Below-the-line funding, which has increased in recent years, may be awarded to districts on a grant-application basis or at the discretion of the PED. This goes against the equalization spirit of the SEG.

The operating budget draws from all state funding except for capital outlay and debt service. It supports all operating expenditures, including instruction, social supports (such as school nurses and counselors), food, bus service, and the like.

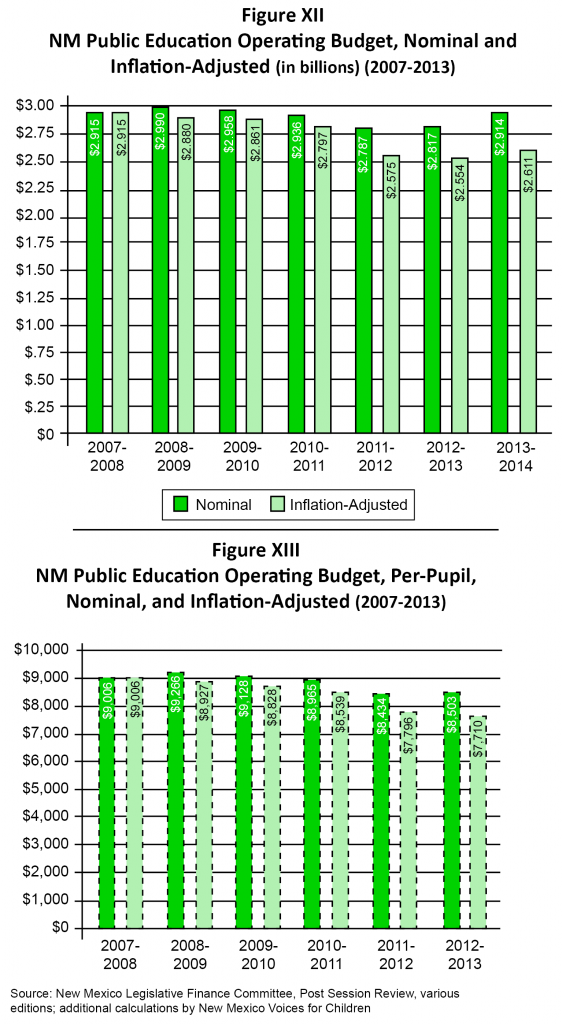

Figure XII shows that as of 2013-14 New Mexico’s public school operating budget had not reached the 2008-09 level of $2.99 billion in nominal dollars (the dark green bars). The picture is even worse in inflation-adjusted terms (indicated by the light green bars), as the value of the 2013-14 operating budget is only $2.61 billion compared to the pre-recession level of $2.91 billion in 2007-08. In real terms the value of the operating budget had fallen by 10.4 percent between 2007-08 and 2013-14.

Figure XIII shows that on a per-pupil basis—which includes enrollment growth—the public school operating budget had fallen even more—by 14 percent—from its peak in 2008-09 to 2012-13 when adjusted for inflation. Again, even on a nominal basis, per-pupil funding was still below pre-recession levels.

Public School Funding in Court

Two lawsuits were filed against New Mexico’s Education Secretary-Designate Hanna Skandera and the state’s Public Education Department in the spring of 2014. In March, a suit was filed in state district court on behalf of parents and students by the New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty and the Rosebrough Law Firm. The suit alleges that the state has failed to provide “a uniform system of free public schools for the sufficient education of all the children of school age as mandated by the New Mexico State Constitution.”2

The suit also alleges that the funding formula fails to provide the additional resources needed for children living in poverty and English language learners, and that recent increases in “below-the-line” funding are in violation of the uniformity requirement of the educational mandate in the state constitution.

The second lawsuit was filed in April by MALDEF (Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund) on behalf of parents and students in northern New Mexico.3 Although there is some overlap—the MALDEF suit reiterates the funding shortfalls for low-income students and English language learners—this suit also alleges that “unfair and non-transparent school accountability grading and teacher evaluation systems”4 deny New Mexico children their constitutional right to “access the educational opportunities they need to succeed in the classroom.”5 The MALDEF suit also calls upon the state to support and fully implement the Indian Education Act, the Hispanic Education Act, and the Bilingual Multicultural Education Act, and alleges that the state has failed to expand pre-kindergarten to ensure access to all at-risk children.

While the lawsuits are a positive development in the fight for sufficient funding for public education, it may take several years for both suits to work their way through the system.

Policy Recommendations

New Mexico should provide sufficient funding for public education as mandated in the state constitution without parents, students, and others having to file lawsuits. The court process can be lengthy and New Mexico’s most vulnerable children need adequate support now if they are to have the best shot at a successful future. The purposes of the lawsuits align with our policy recommendations:

- Per-pupil, inflation-adjusted spending needs to not only be restored to pre-recession levels, it needs to be increased as indicated in the 2008 study. If necessary, the needed revenue should be raised by increasing taxes on New Mexico’s highest-earning households or by closing tax loopholes for profitable businesses.

- The funding formula should be revised so that more resources are invested in the school districts that need them most due to high levels of child poverty and the prevalence of English language learners.

- The Indian Education Act, the Hispanic Education Act, and the Bilingual Multicultural Education Act should be supported and fully implemented.

- Fewer resources (money and valuable teaching time) should be spent on standardized testing.

- Voluntary pre-kindergarten should be funded to allow enrollment of all 4-year-olds (with the funding split between PED and the Children, Youth and Families Department as stipulated in the Act), and policy-makers should look at the data on the efficacy of a full-day program.

- Funding for high-quality child care and parental education programs should be increased. These programs help children develop the skills needed to succeed when they enter kindergarten and help parents be more engaged in their children’s education. As with pre-K, such programs also are an excellent investment as they save significant amounts of money down the line, starting with the reduced need for remedial and special education services in K-12 classrooms. A larger investment in early childhood would better leverage our much greater investment in K-12, as fewer children would start school behind.

Conclusion

The Great Recession severely hindered New Mexico’s ability to provide sufficient funding for public K-12 education. The recession-caused loss of revenue was overcome to some extent by a short-term infusion of federal funding through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. New Mexico lawmakers did not seek other means of raising revenue to fill this gap, and so on a per-pupil, inflation-adjusted basis, the public school operating budget is still 14 percent below what it was before the recession began. While spending has increased as state revenues have begun to recover, much of the new revenue has been given away in corporate tax cuts for which there is no accountability.

This funding gap has meant that the state has not been meeting the needs of New Mexico’s children, especially those children from low-income families, the majority of whom are racial or ethnic minorities. Clearly, state leaders need to restore and increase funding in our school system and for programs that provide children from low-income families with the opportunities that will help lessen the achievement gap. These investments need to go beyond per-pupil, K-12 spending and start long before children enter kindergarten. It remains to be seen whether the recently filed lawsuits will have to be pursued through the system in order for funding levels to be increased.

Endnotes

1. “An Independent Comprehensive Study of the New Mexico Public School Funding Formula,” American Institute for Research, 2008

2. https://povertylaw.org/WP-nmclp/wordpress/WP-nmclp/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Complaint-Stamped-2014-19-3.pdf

3. http://www.maldef.org/assets/pdf/MartinezvNewMexico_Complaint_04114.pdf

4. “MALDEF Challenges New Mexico’s Denial of the Fundamental Right to Education in Most Comprehensive Educational Opportunity Lawsuit Yet Filed,” MALDEF news release, April 1, 2014

5. Ibid