Increasing Access to Post-Secondary Education, Credential Attainment, and Economic Security for New Mexico’s Many Low-Skill and Low-Income Workers

Download this report (Sept. 2014; 20 pages; pdf)

Download the companion presentation (23 slides; pdf)

Link to the press release

by Armelle Casau, Ph.D.

New Mexico has long had difficulty attracting new businesses and high-wage jobs to the state. Companies look at several factors when determining where to locate. Among them are factors we can do little to change—such as geography and natural resources. One factor we can change is the quality of our workforce. Unfortunately, New Mexico does not compare favorably to the rest of the nation when it comes to the educational levels of our working-age population. Given our low rates of educational attainment, it’s not surprising that New Mexico ranks poorly in the percentage of working families that are living at or below the federal poverty level (FPL). Working adults who live in poverty generally lack the financial resources to improve their lot by furthering their education. In turn, their children are less likely to succeed in school than their counterparts from higher-income families, thus continuing the cycle of low-wage work and poverty.

To break this cycle, states offer a variety of programs to help low-skilled workers receive basic education, occupational training, and certification, and/or earn a college degree. In New Mexico, these programs are disjointed and underfunded. Currently, adults in New Mexico who need to improve their literacy, math, and English proficiency skills, and earn high school equivalency credentials typically first enroll in adult education programs—like adult basic education (ABE), adult secondary education (ASE) or English as a second language (ESL). If they finish those programs, they then must enroll in a community college or an occupational skills training program where they can gain workforce skills and earn industry-recognized credentials. Unfortunately, completion rates in this fragmented approach are low, as are the rates of students who transition to college.

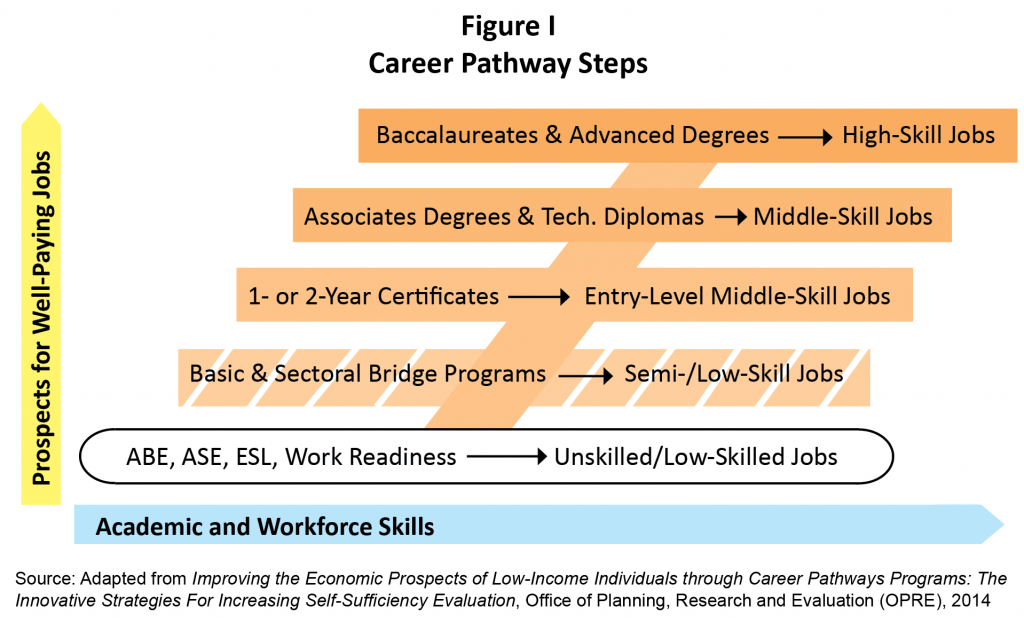

New Mexico should develop and invest in a comprehensive career pathways framework that moves non-traditional adult students along a continuum into post-secondary education. As implemented in many other states, a career pathways framework weaves together and aligns adult basic education programs, workforce training, and college courses while offering comprehensive student support services.1,2 As first steps, so-called bridge programs connect adult education to colleges and careers by simultaneously integrating basic skills and technical instruction, and preparing participants for college-level courses3 (see Figure I for a diagram of typical career pathways steps).

Strongly and collectively supported by the U.S. Departments of Education, Labor, and Health and Human Services, career pathways are effective because they are organized in series of manageable, stackable, interconnected, and credit-bearing steps that prepare and support individuals to quickly reach higher levels of education and gain industry-recognized, post-secondary credentials that can lead to employment in high-demand occupations.4

States across the nation are actively fostering strong partnerships for career pathways programs among adult education and technical education providers, colleges and universities, workforce development stakeholders, human services agencies, and employers. New Mexico should do the same to serve its many low-skilled and low-income adults. New Mexico’s businesses and industries would benefit from a more qualified and productive workforce and the state would be more competitive and its economic future would look brighter.

Low Educational Attainment and Income

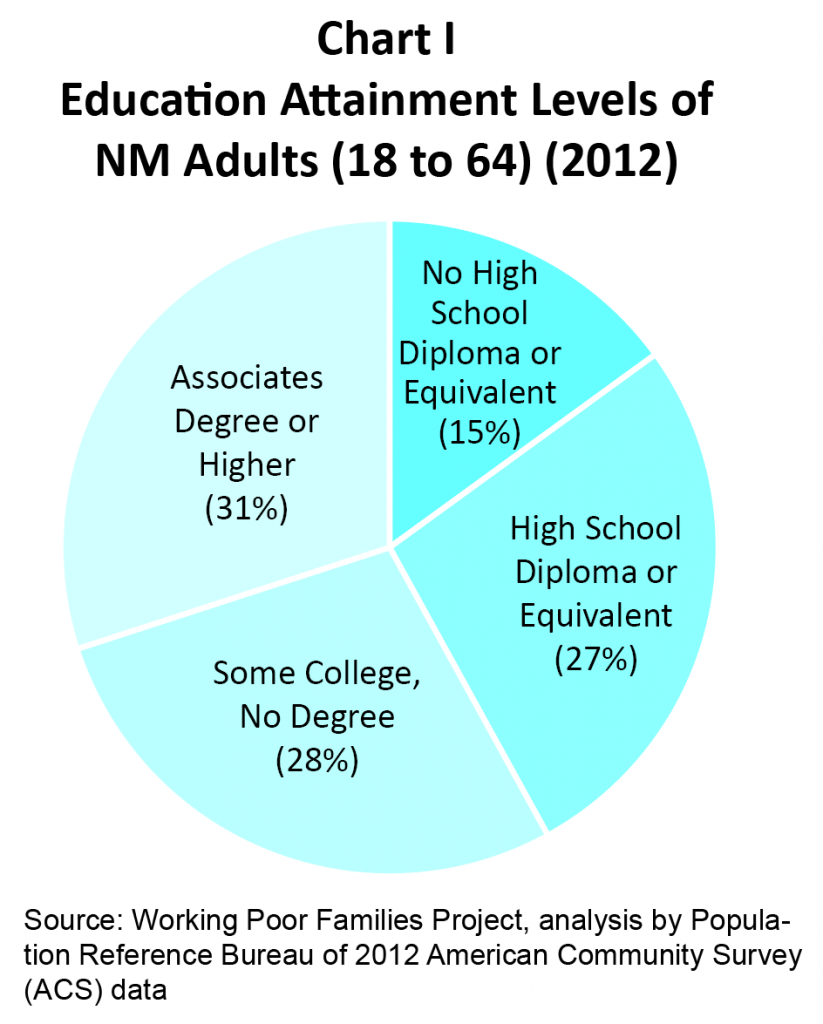

New Mexico’s labor force has significantly lower levels of educational attainment than those in most other states. Of the 1.3 million adults ages 18 to 64 in New Mexico, 69 percent (or almost 890,000) are without a college degree and 15 percent (more than 190,000) have no high school diploma or equivalent (see Chart I). In addition, 9 percent (almost 120,000) have difficulty with English.5

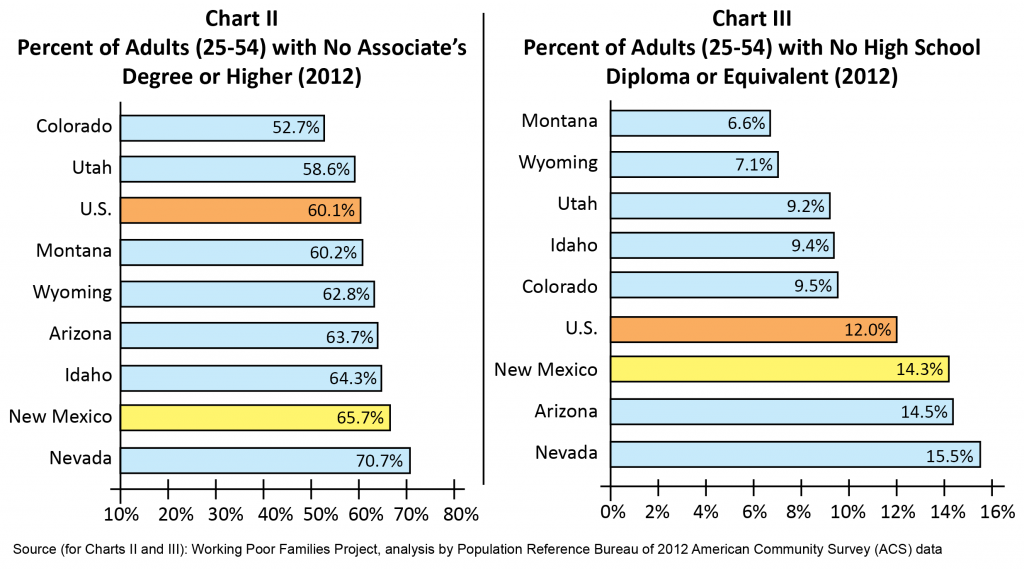

Looking specifically at adults aged 25 to 54—the age group that makes up almost two-thirds of adult education participants in the state—New Mexico ranks 45th nationally for the percentage with no high school diploma or equivalent, and 41st for the percentage with no associates degree or higher. New Mexico also doesn’t fare well compared to other states in the mountain west region. Of the 800,000 adults ages 25 to 54, almost 66 percent (about 530,000) are without a college degree (see Chart II) and 14 percent (110,000) have no high school diploma or equivalent (see Chart III). The educational deficits of New Mexico’s workforce set up barriers to economic development for the state.

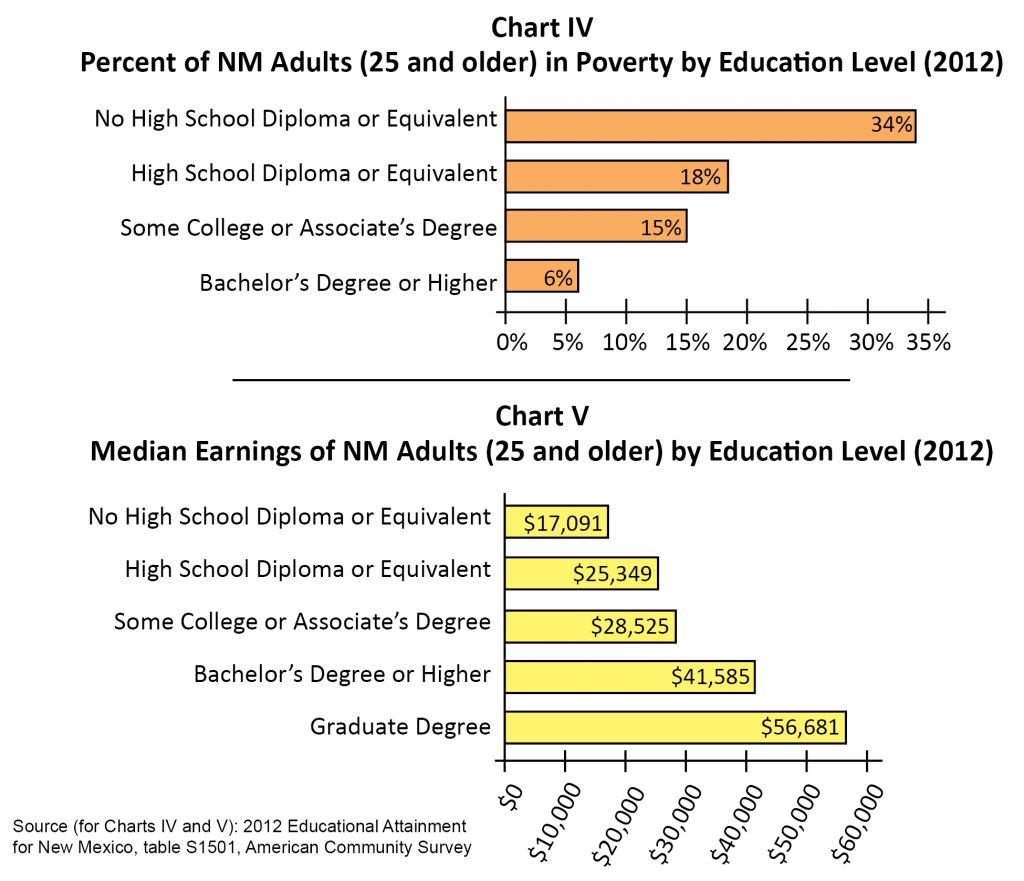

One’s earning potential is closely linked with their educational level—more education generally leads to more money. Not surprisingly, low-income families in New Mexico tend to have low levels of educational attainment. An estimated 31 percent of low-income families—those that live below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), meaning they earn $47,700 or less for a family of four—have at least one parent without a high school diploma or equivalent and 46 percent have no parent with any post-secondary education. Additionally, 25 percent of low-income families have at least one parent who has difficulty speaking English, which makes it harder for these parents to get jobs paying family-sustaining wages and to participate fully in their children’s education.

The situation is worse for poor families—those making below 100 percent of FPL ($23,850 or less for a family of four)—with 38 percent having at least one parent without a high school diploma or equivalent, 51 percent having no parent with any college, and 30 percent having at least one parent who has difficulty speaking English.6

With higher levels of education, New Mexico workers would significantly reduce their chances of living in poverty and increase their chances of earning family-sustaining wages (see Charts IV and V).

Still Working, Still in Poverty

By and large, New Mexico’s poor and low-income families are working hard but are still unable to become financially secure and independent. More than half of our poor families are working, as are nearly three-quarters of our low-income families. These rates are slightly higher than the national average.7

Overall, too many of New Mexico’s working families struggle economically. Almost 16 percent of all working families (32,320 families) are poor and nearly 43 percent (88,745 families) are low-income. Nationally, just 11 percent of working families are poor and 33 percent are low-income (see Charts VI and VII). This places New Mexico 49th in the nation for both indicators—only Mississippi fares worse.

What’s bad for working families is bad for their children. Almost half of New Mexico children under age 18 (48 percent or 207,735) live in working families that are low income, and almost one-fifth (19 percent or 83,035) live in working families that are poor. We rank 49th in the nation in both of these indicators as well.8

Too Many Low-Wage Jobs

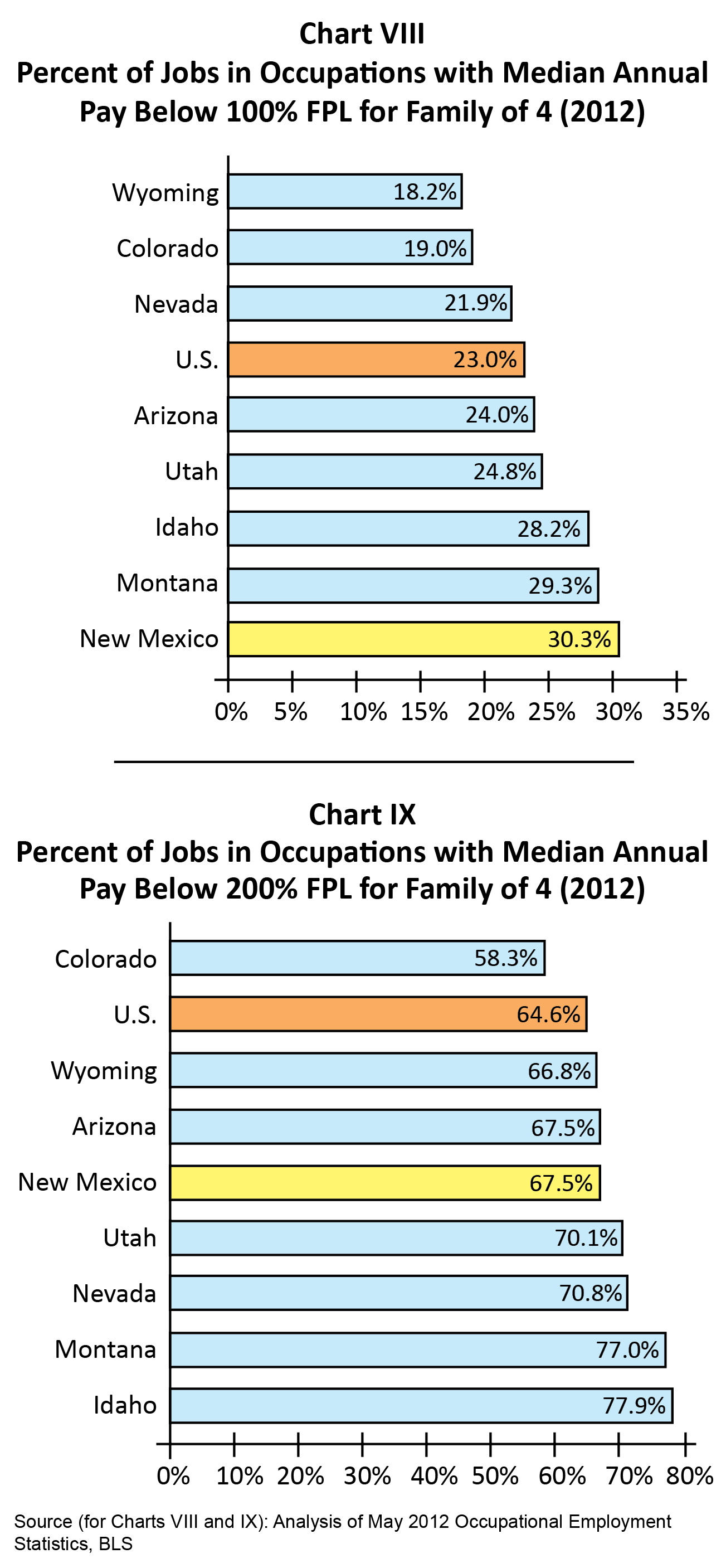

When we look at median wages, we can see why many families have a hard time making it economically. In New Mexico, 30 percent of our jobs (more than 250,000 jobs out of nearly 840,000 total) are in occupations with poverty-level wages for a family of four ($23,850 or less). New Mexico has the highest percentage of such jobs in the mountain west region (see Chart VIII) and ranks 43rd nationally. New Mexico does slightly better than some states in the region when looking at jobs that pay low income wages (see Chart IX), but fully 68 percent of jobs pay wages too low to adequately support a family of four ($47,700 or less). Unfortunately, we are unlikely to lure higher-wage jobs until we can offer companies a more educated and skilled workforce.

Not Enough Middle-Skill Workers

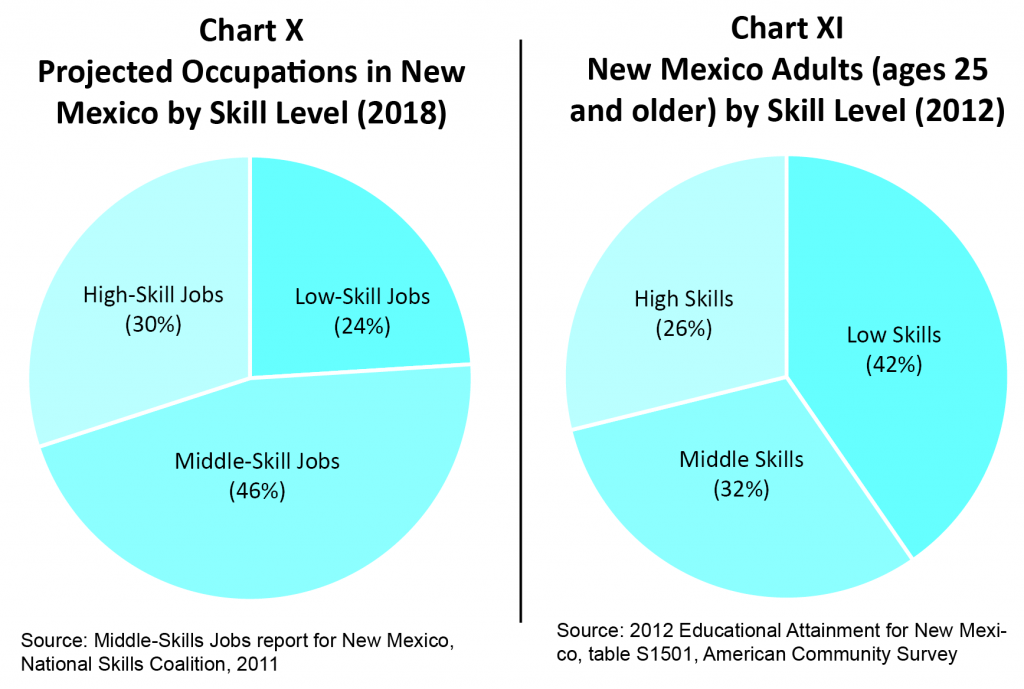

Middle-skill jobs are those that require more than a high school diploma but less than a four-year degree. These types of jobs are very good for New Mexico since they usually offer family-sustaining wages. Unfortunately, there are just too many low-skill workers and not enough middle-skill workers in the state. Based on data from New Mexico’s Department of Workforce Solutions (DWS), the National Skills Coalition estimated that in 2018, 24 percent of jobs will be low-skill, 46 percent of jobs will be middle-skill, and 30 percent will be high-skill (see chart X). Unfortunately, looking at 2012 data, 42 percent of adults over 25 years of age in Mexico were low-skilled, 32 percent were middle-skilled, and 26 percent were high-skilled (see Chart XI).

Increasing the number of adults with post-secondary credentials is crucial, as states with high educational attainment levels are also high-wage states.9 It is important to note that educational solutions are needed that go beyond the traditional high school-to-college pipeline since current working adults make up the majority of the future workforce.10

The Current Status of Adult Basic Education

In program year 2012-2013, nearly 19,400 New Mexicans participated in adult education programs, which are administered by the state’s Higher Education Department (HED). The department acknowledges that this represents only about 5 percent of the adults eligible for these educational services and that many adults are stuck on waiting lists. Of those participants:11, 12

- 75 percent were poor (earning less than 100 percent of FPL);

- 69 percent were either unemployed or not in the labor force;

- 19 percent were single parents;

- 55 percent were females and 42 percent were Hispanic females;

- 72 percent were Hispanic and 10 percent were Native American;

- 62 percent were 25 years of age or older;

- 38 percent entered as ESL students;

- 16 percent needed basic literacy instruction (below 4th grade equivalency);

- 38 percent entered at adult basic levels (roughly between 4th to 8th grade equivalency); and

- 9 percent entered at the adult secondary levels (between 9th and 12th grade equivalency).

While these adults need to improve their literacy, math, and English proficiency skills, and earn high school credentials, many also want and need access to career and technical education classes that can lead to employment and self-sufficiency—but few are likely to persevere on that path. In the 2012-13 program year, only about 30 percent of all participants who started adult education programs completed their levels. An estimated 8 percent transitioned into college or occupational training after exiting their program.13

In our current system, a tiny fraction (less than 4 percent) of the adults enrolled in education programs (who are, themselves, a tiny percent age of eligible adults) are participating in the career pathway bridge program I-BEST (described in detail later in this report) that integrates adult education with career and technical skills building. This program is preliminarily yielding a 51 percent program completion rate with earned credentials, with another 32 percent of students still in process, and only 16 percent dropping out or taking a break.14

Low-skilled adults are more likely to persevere when enrolled in programs that combine basic education with sector-based skills building. As one of the states that administers adult education programs through a higher education department (rather than a K-12 education or workforce/labor department, as in some states), New Mexico has an opportunity to better integrate ABE services with career-focused courses and higher education institutions to increase post-secondary credential attainment. Unfortunately thus far, most of the attention has been on just building basic skills rather than on offering career pathways to provide effective ways out of poverty.

New Mexico adults are eager to earn industry credentials and college degrees to improve their economic security. New Mexico was recently ranked first in the nation for the percentage of adults enrolled at least part-time in post-secondary institutions (10 percent in the state compared with 7 percent nationally).15 Unfortunately, the state ranks 46th in the nation (and last in the mountain west region) in the percentage of community college students who go on to obtain certificates or degrees in a 3-year period or transfer to a 4-year college (only 27 percent compared with the national average of 38 percent).16 More needs to be done to make college completion a feasible and successful option for low-skilled workers.

An Insufficient Investment

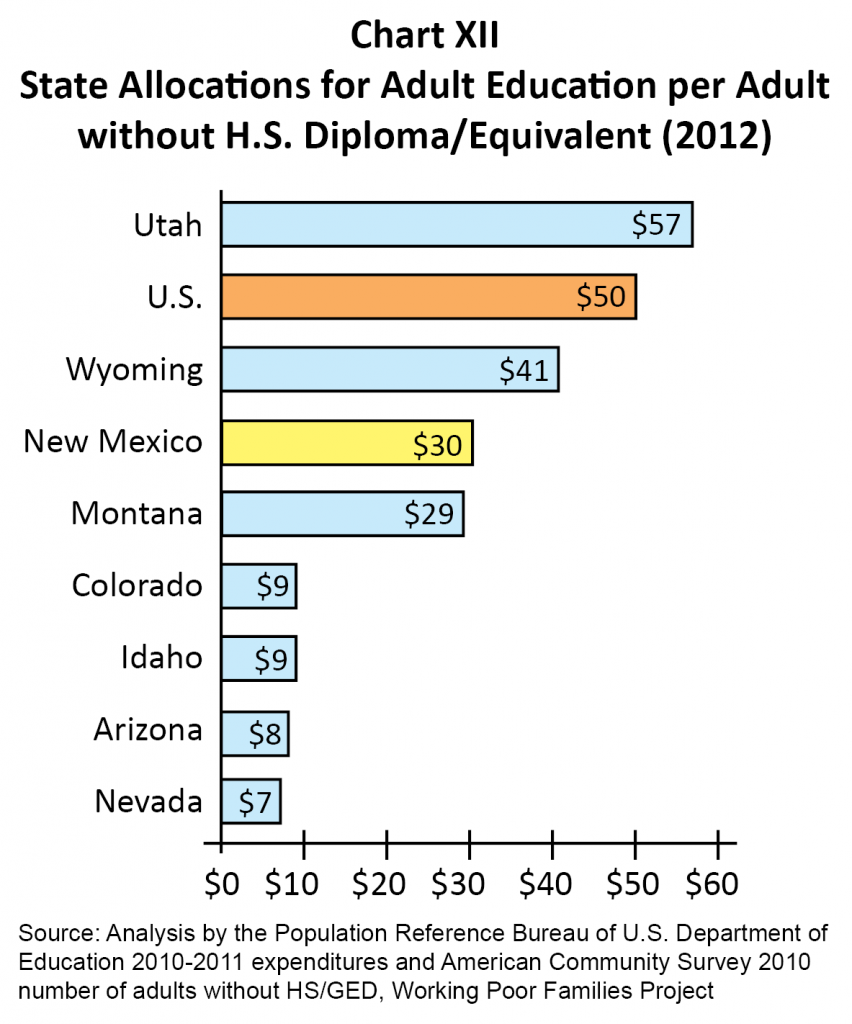

In New Mexico, about $9.6 million was invested in adult education programs in fiscal year 2013, with $4.2 million coming from the federal government. The number of funded students is still down almost 20 percent since the program year 2009-2010 when the state began cutting funding.17 The national average for state-allocated resources for adult education and literacy is $50 per adult without a high school diploma or equivalent. All of the mountain west states except Utah invest less than the national average, with New Mexico spending just $30 per adult (see Chart XII).

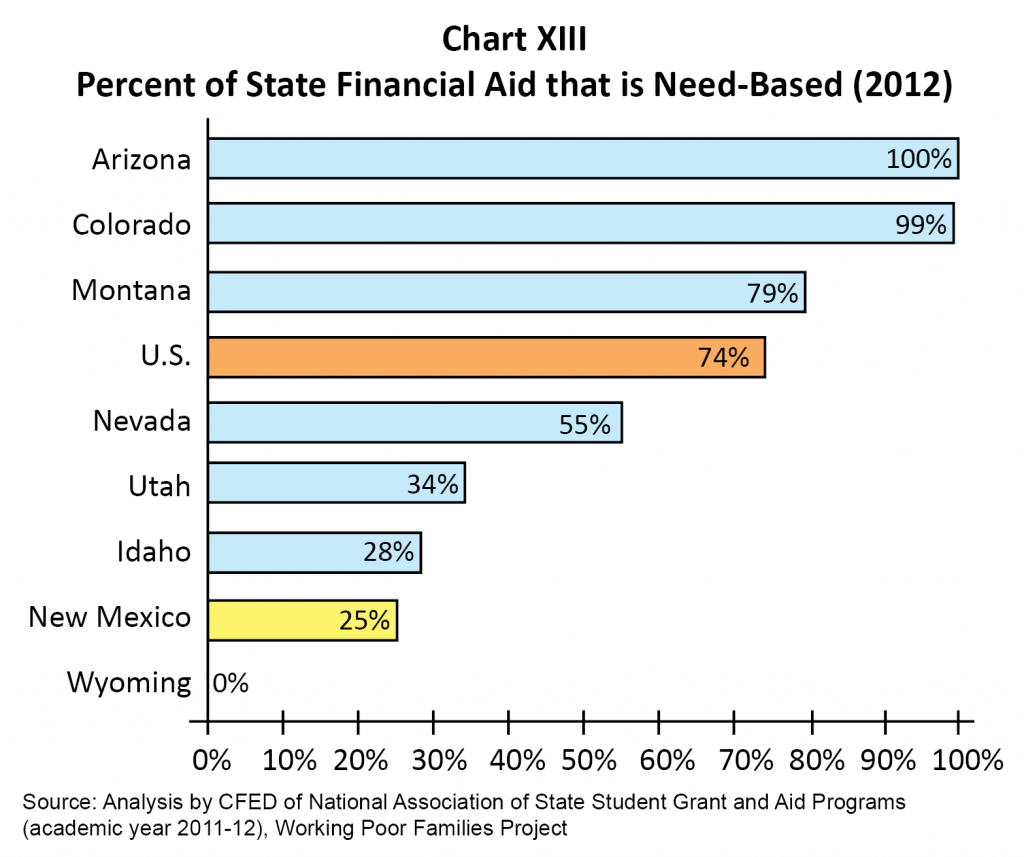

Even though overall funding for these programs in New Mexico has decreased in recent years, bills introduced during the 2014 legislative session for additional funding either did not pass or were pocket vetoed. What’s more, despite its high poverty rate, New Mexico awards a very small percentage of its state-funded college financial aid on a need-basis compared with the national average (see Chart XIII). The mountain west states of Colorado and Arizona provided 99 and 100 percent, respectively, of their financial aid on a need-basis.

Many states that invest heavily in adult education programs, like Connecticut ($183 per adult) and Vermont ($175), also rank high in the educational attainment of their adult workforce. In the mountain west region, there is a rough correlation between states that invest in these programs and states that have better educational attainment numbers. Colorado is a stand out: it has not traditionally funded ABE well and yet has relatively high educational attainment rates. This is known as the “Colorado Paradox,” in which the high educational attainment numbers are attributed to talent imported from other states rather than sufficient educational investments in its homegrown population. In the past couple of years though, Colorado has made adult education more of a priority. In 2014, with support from the business community, the state appropriated nearly $1 million in funding for bridge career pathways programs that require ABE providers to work with at least one post-secondary institution and one workforce development provider to help break institutional silos and better align adult education programs with occupational skills training programs.18, 19

In 2014, governors and legislators from 14 other states enacted legislation to invest in career pathways, foster sector partnerships, and align data and systems to help close the middle skills gap.20 In addition, the recent reauthorization of the federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) presents states with an opportunity to capitalize on the federal government’s commitment to more effectively promote career pathways and sector partnerships.

A First Step toward Career Pathways

A few years ago, New Mexico took a first step toward building a career pathways program. NM HED was awarded an Accelerating Opportunity (AO) grant from the Gates Foundation in 2011. This $200,000 planning grant was for starting a career pathways bridge program called I-BEST (Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training) at six community colleges. Bridge programs like I-BEST—often first steps on career pathways—offer streamlined and integrated classes that accelerate skill building by combining basic education with technical training. In this contextualized learning, students improve their language and college skills in the context of their field of study.

Currently more than 20 states are trying the I-BEST model (while other states have implemented different types of bridge programs) and many use a co-teaching strategy where classes (including ESL) are co-taught more than 50 percent of the time by an adult education instructor and a career and technical education instructor (CTE) to ensure that students gain basic and occupational skills simultaneously for accelerated learning. As in other states, I-BEST programs in New Mexico offer courses of study that vary across sites and are matched to DWS job projections and, therefore, tailored to the needs of local communities and focused on high-growth occupational areas. The fields of study range from electrical trades to welding, pharmacy technicians, wind energy, home health aides, plumbing, early childhood multicultural educators, and certified nursing assistants. Despite the high success rate mentioned earlier, less than 4 percent of New Mexico’s nearly 20,000 adult education participants are enrolled in I-BEST programs.

The state, unfortunately, opted to not apply for the implementation phase of the AO project to scale up I-BEST, but a three-year Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training (TAACCCT) grant from the U.S. Department of Labor was secured to develop a Skill Up Network (SUN) to expand and improve the capacity of community colleges to provide education and career training programs that can be finished in two years or less. The TAACCCT grant currently funds four program components in New Mexico: an online course-sharing system across 13 colleges; a system to grant credit for prior learning; information technology entry-level certificates; and I-BEST. This grant, which has enabled the I-BEST program to continue, ends in the fall of 2014 and state monies have not been allocated to sustain it once the federal money runs out.

I-BEST is only one example of a bridge component along a career pathways framework. Moving forward, New Mexico should focus on developing a statewide career pathways framework that focuses on a couple of key sectors (like nursing or early childhood education, for example) and that includes well-integrated bridge programs in the career pathways pipeline. Overall, effective career pathways frameworks in other states have been found to include:21, 22, 23

- Well-articulated, short-term, and stackable training steps with multiple entry and exit points that encourage student persistence;

- On-ramps and off-ramps to ease access to adult education, career programs, and post-secondary institutions, as well as transition back into the workforce;

- Continually adjusted and well-defined pathways that provide clear paths to post-secondary, industry-recognized credentials in key industry sectors;

- Contextualized learning so low-skill students can improve their language and college skills within the context of their chosen field of study for accelerated learning;

- Comprehensive assessments that enable participants to enter at appropriate steps;

- Accelerated and flexible programs that recognize the needs of non-traditional adult student populations with changing personal and work situations;

- Comprehensive support services including academic supports (tutoring and help with educational plans), personal guidance (one-on-one case management and group-level assistance), and supplemental support services (child care assistance, transportation vouchers, and financial assistance to cover tuition, books, and other costs); and

- Strengthened partnerships between stakeholders including community colleges, ABE providers, state agencies, workforce development boards, and employers.

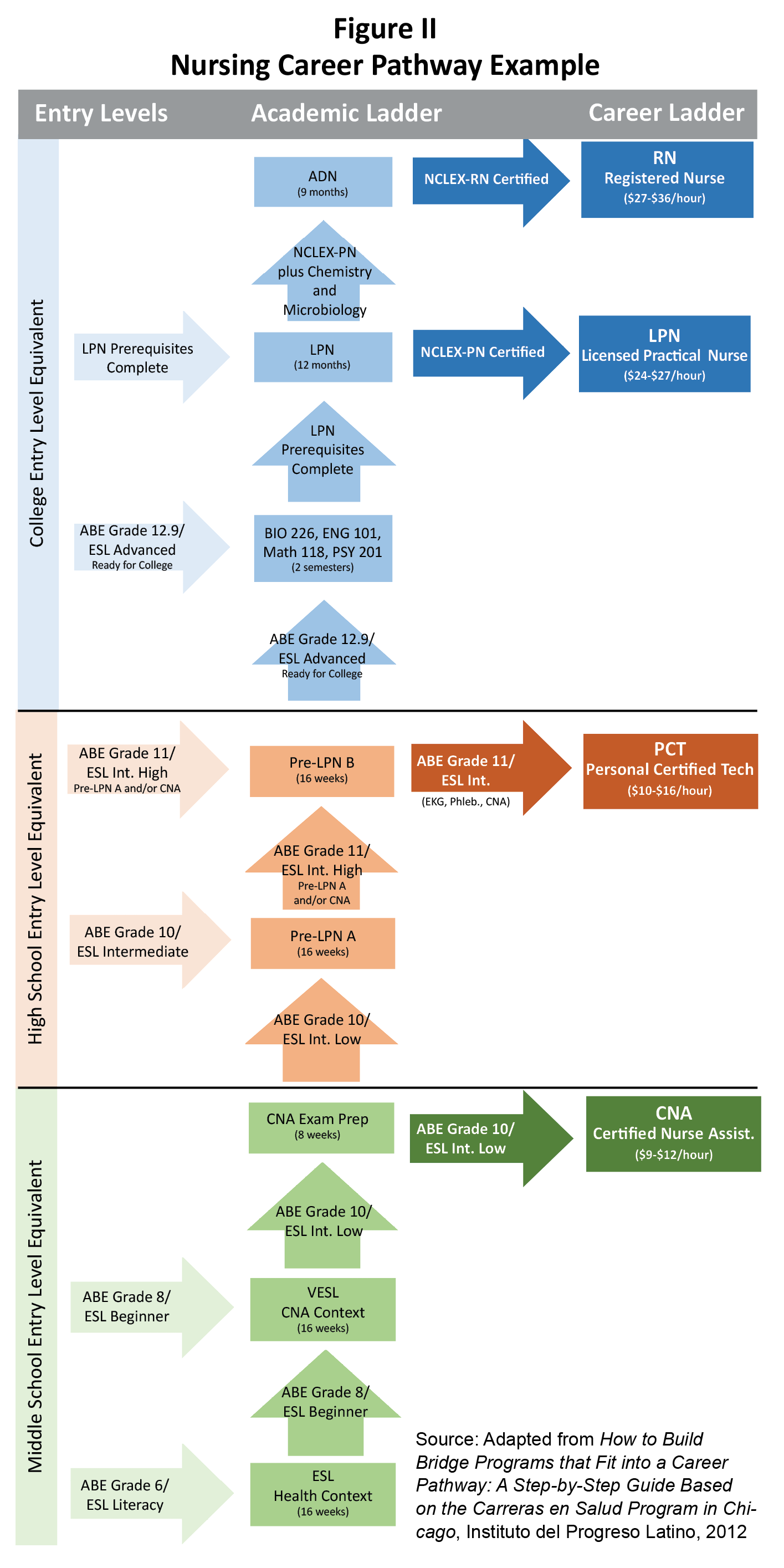

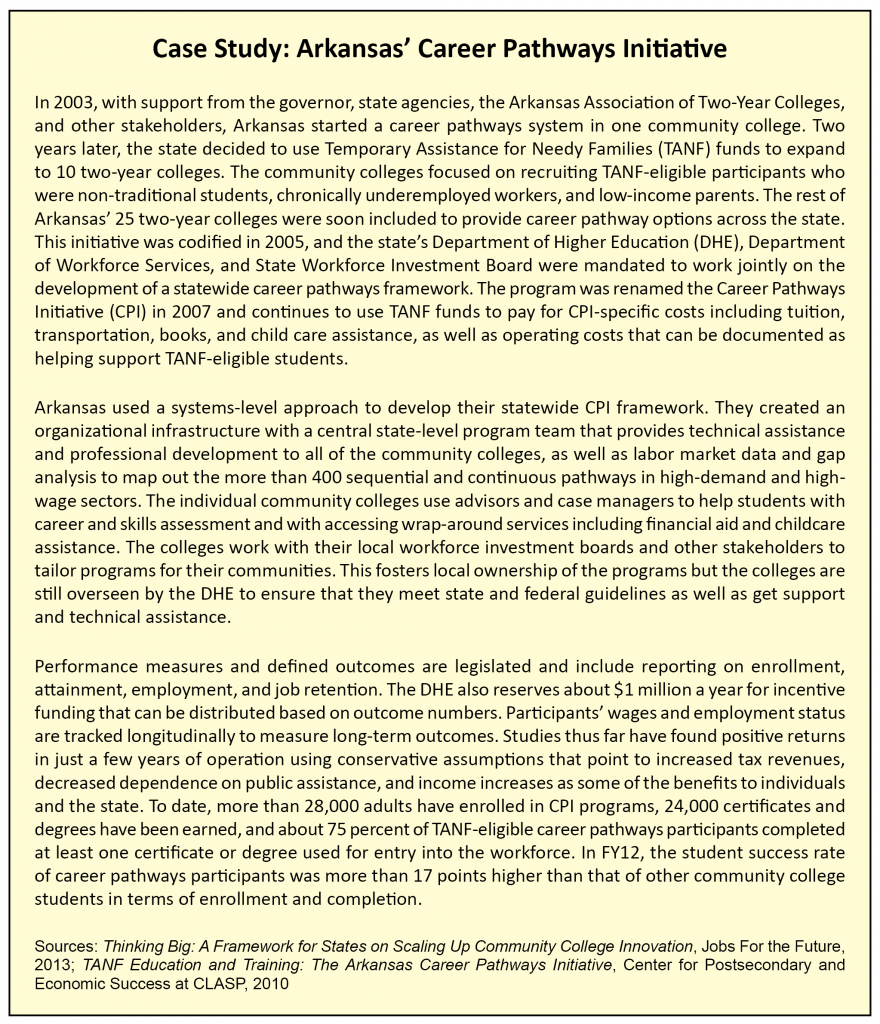

Figure II is an example of the academic and career steps of a health care career pathway. It includes bridge programs for students to enter at multiple points along the pathway, short-term and stackable steps with connecting points, and clear lines-of-sight to certificates with matched expected wage earnings. States with effective career pathways frameworks actively identify, develop, and articulate credential attainment pathways for their high-growth occupations. The case study (see boxed text) details some of the steps the state of Arkansas and its community colleges took in building its comprehensive career pathways framework.

Return on Investments on Adult Education and Career Pathways Programs

Overall, even with low completion rates, adult education programs have high rates of return on investment (ROI). Based on the calculations of NM HED, the state’s investment of just $5.4 million generated almost $36 million in savings (including savings on public assistance), added economic growth to the state (through higher earnings), and increased income for the participants (including new employment and job promotions). Every dollar the state invested in adult education yielded more than $5 in benefits to individuals, the state, and the economy.24 This number is comparable with ROIs in other states.

New Mexico could leverage this positive ROI and compound it with the added benefits of career pathways programs. Researchers in Washington state, where I-BEST was started, have found that I-BEST students are three times more likely to earn college credits, nine times more likely to earn workforce credentials, and are employed at double the number of hours per week (35 versus 15 hours) when compared with non-I-BEST students.25 In 2013, an analysis for the I-BEST model in Washington state found an ROI of 329 percent for student completers based on wage gains over the students’ lifetime. The same study showed other financial benefits with a positive ROI of 42 percent in the form of higher tax receipts and lower social costs.26

As discussed earlier, the I-BEST bridge program in New Mexico is showing great promise with 84 percent of participants either having completed their programs, earned certificates, or still in progress and less than 16 percent having dropped out or stopped for now. A 2014 study by the state Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) pointed out that the state’s consecutive method—first, adult education and then, technical/career programs—requires on average that students enroll in five semesters of courses at a cost of $3,800 per student. The integrated NM I-BEST model only takes two semesters to complete at a cost of $2,000.27 This is a win-win for the students in terms of time commitment and for the state in terms of investment and positive outcomes.

As another example of positive impacts of career pathways, researchers looking at Minnesota’s FastTRAC found that 88 percent of participants in the integrated credit-bearing courses completed their programs and/or earned industry-recognized credentials, compared with traditional programs where just 25 percent completed their remedial courses and only 4 percent had completed a degree or certificate in the five years following enrollment.28

The momentum for career pathways, including bridge programs, has increased in recent years. Many federal agencies, philanthropic organizations, state policy makers, PSE institutions, workforce development groups, human services state agencies, and industries are converging on the positive impacts and outcomes that career pathways yield for low-income and low-skilled adults looking to earn post-secondary credentials that can lead to economic security for themselves and their families.

Policy Recommendations

In 2010, Skills2Compete-New Mexico, a convening by the National Skills Coalition, created a platform of priorities to ensure that our state’s workforce had the necessary skills to compete. Core advisors included representatives from state agencies as well as business, education, workforce, advocacy, and funding stakeholders.29 Some of the recommendations focused on creating career pathways and included the need to:

- Better coordinate and align adult education programs and post-secondary institutions;

- Focus on high-growth occupations and industry needs to create effective career pathways;

- Create accessible career pathways based on best practices for instruction and curriculum;

- Increase funding for adult education and career pathways programs;

- Provide targeted financial and student support services; and

- Develop incentives for institutions and programs to increase middle-skills gains.

These priorities, bolstered by the shift towards career pathways in numerous other states and at the federal level, are very much in line with the policy recommendations listed below.

Revamp the ABE state plan to focus on career pathways and transition to college. The current state plan for adult basic education and family literacy, which has not been updated since 2006, only briefly mentions the need for post-secondary institutions to better integrate adult education with occupational training programs.30 The ABE state plan is currently being revised and should have as priority goals the transition of participants into college and the creation of a statewide career pathways framework. (See Illinois’ ABE visioning document for examples of recommendations to address the changing needs of adult learners in the 21st century economy.31)

NM HED could take the lead on designing and implementing a career pathways framework that supports community colleges and their many low-income, low-skilled adult student populations, much like in Arkansas. The plan would need to include systems-level strategies to increase the availability of and access to well-defined and articulated career pathways components, including bridge programs like I-BEST, and comprehensive adult student support services. The New Mexico Association of Community Colleges, the New Mexico Independent Community Colleges, the New Mexico Adult Education Association, and the two-year post-secondary institutions themselves should partake in the process and leverage existing community college infrastructures, capacity, and programs already in place. Four-year colleges and universities should also be key partners in the process.

A promising partner is the DWS, which has expressed interest in career pathways programs since they can improve the economic security and employment status of adults across the state. The DWS is currently looking into ways to reduce hurdles in data sharing; better involve Workforce Investment Boards (WIB) and one-stop centers in career pathways; and more effectively integrate and locate its staff on community college campuses to help advise students with career decisions and transition into the workforce. Another key partner should be the New Mexico Human Services Department which oversees support services, including the TANF program, that help low-income individuals and families become economically secure.

Determine adult education funding and workforce development needs. In 2014, a legislative memorial unanimously passed the state House (although not the Senate) requesting that HED form a work group to study the feasibility of fully funding the formula for adult education programs. Convening this work group would give stakeholders in the adult education community—including community colleges, workforce development groups, and state agencies—an opportunity to research career pathways and make recommendations to legislative committees. As requested by some legislators, the state should also fund a workforce gap forecasting study to determine how HED, DWS, and the Economic Development Department can identify strategies to address future workforce development needs.

Expand and refine performance measures to focus on educational and economic outcomes. Since fiscal year 2011, the funding formula for ABE has been partially based on performance. As recommended by the LFC, the HED should implement additional well-defined accountability and outcome measures to further help incentivize education programs that successfully enroll and support adult students looking to earn college credentials (data should be disaggregated by income and skill level to see how different student populations fare). Adding performance measures that can better track employment outcomes can also help generate statistics for ROI studies and entice community colleges to collaborate with DWS, WIB, and employers to better assist and advise adult students as they transition into, and successfully remain in, the workforce.

Restore the College Affordability Fund and broaden eligibility requirements. Adult education programs, when they are available, are usually offered free-of-charge but career pathways programs and college credit courses have fees that can be cost-prohibitive to low-income students. WIA funds and private scholarships are sometimes available but many students pay at least half of the fees, which can amount to a few thousand dollars. In addition, the federal financial aid available to students without a high school diploma or equivalent has been scaled back. Looking at the student populations attending community colleges in New Mexico, 65 percent are taking courses part-time since many need to work to pay for living expenses. Of those part-time students, nearly 75 percent are 22 years of age and older and have already been out of high school for a few years.32 These non-traditional students do not qualify for the New Mexico lottery scholarship, which requires students to be no more than one year out of high school and to carry a full course load of 15 credit hours.

New Mexico should improve college affordability for low-income adults by providing state-funded need-based financial aid. Restoring the currently empty College Affordability Fund would provide need-based tuition assistance to those who have been out of school for more than a year and may not qualify for merit scholarships. Eligibility should also be broadened to include degrees and professional certificates from two-year colleges and to allow non-traditional students to take fewer courses at a time to more easily fit school into work schedules.

Provide integrated student support services including child care assistance. Student support services, including child care assistance, are an integral part of effective career pathways. Eligibility for child care assistance should be increased from the current 150 percent of FPL to at least the pre-recession 200 percent of FPL to help all low-income parents. Access to high-quality child care is an effective two-generation solution that provides early childhood education to young children while enabling parents to increase their education and earn marketable credentials. In studies of student parents taking classes at community colleges, researchers found that between 60 percent and 70 percent of respondents were dependent on child care services to continue their education.33 An added benefit of parents increasing their levels of education is that their children do better in school.

Utilize unspent TANF funds. The federally funded TANF block grant is targeted to low-income parents and pregnant women to help them achieve economic self-sufficiency. Other states have effectively used TANF funds to pay for career pathways program components including vocational training, post-secondary education, and child care assistance.34 In the past few years, New Mexico has rolled over tens of millions of dollars of unspent TANF funds that could be used now to help low-income families earn credentials and weather the persistent economic downturn. Data show that about 10 percent of TANF recipients are enrolled in education and/or training in New Mexico (the national average is 9 percent).35 New Mexico should follow the lead of Oklahoma and Georgia, which rank at the top of that category by enrolling more than 30 percent of their TANF recipients in education and training programs.

Integrate with other programs like Education Works, NM Works, SNAP E&T, and JTIP. A well-integrated career pathways framework could synergize with current funding streams and programs that help adults gain workforce skills. Education Works allows TANF-eligible families to focus on increasing their educational attainment while providing them with small stipends to offset some costs. NM Works provides adults access to work-readiness programs and assistance through the state Income Support Division. SNAP E&T (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education and Training) helps SNAP recipients learn skills and get training, education, or work experience that can lead to employment. The Job Training Incentive Program (JTIP) pays for limited classroom and on-the-job training for new jobs created by expanding or relocating businesses.

Conclusion

New Mexico has one of the highest poverty rates in the nation, along with low levels of educational attainment. Even though most of our low-income families are working, they are unable to achieve economic security and become self-sufficient. Our preponderance of low-skill workers and shortage of middle-skill workers have been detrimental to our state’s economy.

New Mexico’s current approach to adult education for low-skill workers is fragmented, underfunded, and reaches far too few of the adults who would benefit. It also focuses on just teaching basic skills instead of integrating them with occupational skills and promoting access to post-secondary education that can lead to higher wages. The state should reassess and increase its current investments in adult education and look into developing a systems-level career pathways framework that includes bridge programs to give low-skill and low-income adults the opportunity to more rapidly earn industry-recognized credentials and certificates while simultaneously increasing basic literacy and math skills as needed.

Revamping this system would provide a win-win outcome—reliance on social services would be reduced, the state’s economy would grow, we would be more likely to lure businesses here that need a well-educated workforce, and the economic security of these families would be improved, which would, in turn, improve the academic and well-being outcomes of their children.

Endnotes

1 Charting a Path: An Exploration of the Statewide Career Pathway Efforts in Arkansas, Kentucky, Oregon, Washington and Wisconsin, Seattle Jobs Initiative, 2009

2 Improving the Economic Prospects of Low-Income Individuals through Career Pathways Programs: The Innovative Strategies For Increasing Self-Sufficiency Evaluation, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation (OPRE), 2014

3 Farther, Faster: Six Promising Programs show How Career Pathway Bridges Help Basic Skills Students Earn Credentials That Matter, CLASP, 2011

4 Joint letter on supporting career pathways from the U.S. DOL, DOE, and DHHS (2012)

5 Working Poor Families Project analysis by the Population Reference Bureau of American Community Survey 2012 data

6 Ibid

7 Ibid

8 Ibid

9 A Well-Educated Workforce is Key to State Prosperity, Economic Policy Institute, 2013

10 New Mexico’s Forgotten Middle-Skill Jobs: Meeting the Demands of a 21st Century Economy, National Skills Coalition, 2010

11 New Mexico Narrative Report from the ABE Division (2012-2013) for a federal annual report

12 National Reporting System for Adult Education in New Mexico (program year 2012-2013), NM HED

13 Ibid

14 Presentation of data by the Center for Education Policy Research (CEPR) at the University of New Mexico during a NM I-BEST Consortium meeting (2014)

15 Working Poor Families Project analysis of National Center for Higher Education Management Systems (NCHEMS) 2009 data

16 Working Poor Families Project analysis of IPEDS 2008 cohort data from College Measures

17 New Mexico Narrative Report from the ABE Division (see note 10)

18 Colorado House Bill 1085: Adult Education and Literacy Act of 2014

19 “State and Local Opportunity Note” on Colorado’s HB 14-1085, Bell Policy Center, 2014

20 State Legislature Round Up, National Skills Coalition, 2014

21 “National Trends in Adult Basic Education,” a Jobs For the Future presentation to a Texas P-16 Council meeting, 2012

22 Career Pathways Toolkit: Six Key Elements for Success, developed by Social Policy Research Associates on behalf of the U.S. Department of Labor, 2011

23 Improving the Economic Prospects of Low-income Individuals through Career Pathways Programs, (see note 2)

24 State of New Mexico Higher Education Department Annual Report, 2013; Ibid

25 “I-BEST Fact Sheet,” Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges, 2012

26 “I-BEST Cost Benefit Analysis Fact Sheet,” Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges, 2013

27 College Readiness in New Mexico, NM Legislative Finance Committee, 2014

28 The Promise of Career Pathways Systems Change: What Role Should Workforce Investment Systems Play? What Benefits Will Result?, Jobs For the Future, 2012

29 Skills2Compete-New Mexico Platform of Priorities, National Skills Coalition, 2010

30 State Plan for Adult Education and Family Literacy, NM HED, 2006

31 Creating Pathways for Adult Learners: A Visioning Document for the Illinois Adult Education and Family Literacy Program: Continuing our Work to Meet Adult Learners’ Needs, Illinois Community College Board, 2009

32 American Association of Community Colleges data for New Mexico. Retrieved from http://www.aacc.nche.edu/Pages/CCFinderStateResults.aspx?state=NM

33 Improving Child Care Access to Promote Postsecondary Success Among Low-Income Parents, Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 2011

34 Funding Career Pathways and Career Pathway Bridges: A Federal Policy Tool Kit for States, Center for Postsecondary and Economic Success at CLASP, 2010

35 Working Poor Families Project analysis of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2011 data

The Working Poor Families Project is funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Ford Foundation, Joyce Foundation, and The Kresge Foundation.