Download the full report, including the data by legislative district (Feb. 2015; 12 pages; pdf)

Download the full report, including the data by legislative district (Feb. 2015; 12 pages; pdf)

Our economy is strong when people have money to spend. When people work full time and still don’t earn enough money to cover the basics, our economy is not at its healthiest. Tax credits for low- and moderate-income families are one way to generate economic activity, particularly when wages are low. In New Mexico, the Working Families Tax Credit encourages work, helps to raise hard-working families out of poverty, and benefits almost 300,000 children, while also pumping millions of dollars into local communities.

While the rest of the nation is recovering from the recession, New Mexico is still struggling to attract jobs and grow the economy. Expanding this credit so it does more for New Mexico’s hard-working low-wage families would pull more children and families out of poverty and benefit local businesses and communities.

The Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC) is the state equivalent of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). A refundable tax credit available to low-income workers, the EITC passed with bipartisan support under President Gerald Ford in 1975. In 1986, the EITC was indexed to rise with inflation under President Ronald Reagan who called the program “the best anti-poverty, the best pro-family, the best job creation measure to come out of Congress.”1 Since then, it has been strongly supported by lawmakers on the national level and in several states. New Mexico enacted the WFTC in 2007. It is worth 10 percent of the value of the federal EITC and provides additional benefits for New Mexico’s working families and communities.

How the Credits Work and Who Claims Them

Eligibility for the credits depend on a filer’s earned income, marital status, and the number of dependent children. For tax year 2014, working parents who have incomes of up to $38,500 (for a single parent with one child) and $52,400 (for a married couple with three or more children) can receive the credits. Workers with no children must earn no more than $14,600 (or $20,000, if married and filing jointly) to qualify for credits. The value of the refunds range between about $500 and $6,100 for the EITC and $50 to $600 for the WFTC. The refund amounts rise as earned income increases until they reach a maximum level, at which point they plateau and then phase out as income increases.

In the 2012 tax year, the most recent year for which the data are available, more than 212,000 New Mexico individuals and families (or 26 percent of the tax returns filed in the state) claimed the EITC and WFTC.

That year, New Mexico’s working families received nearly $500 million from federal returns and nearly $50 million from the state. The average credit amount for each New Mexican tax return was about $2,600 when the two refunds are combined.2

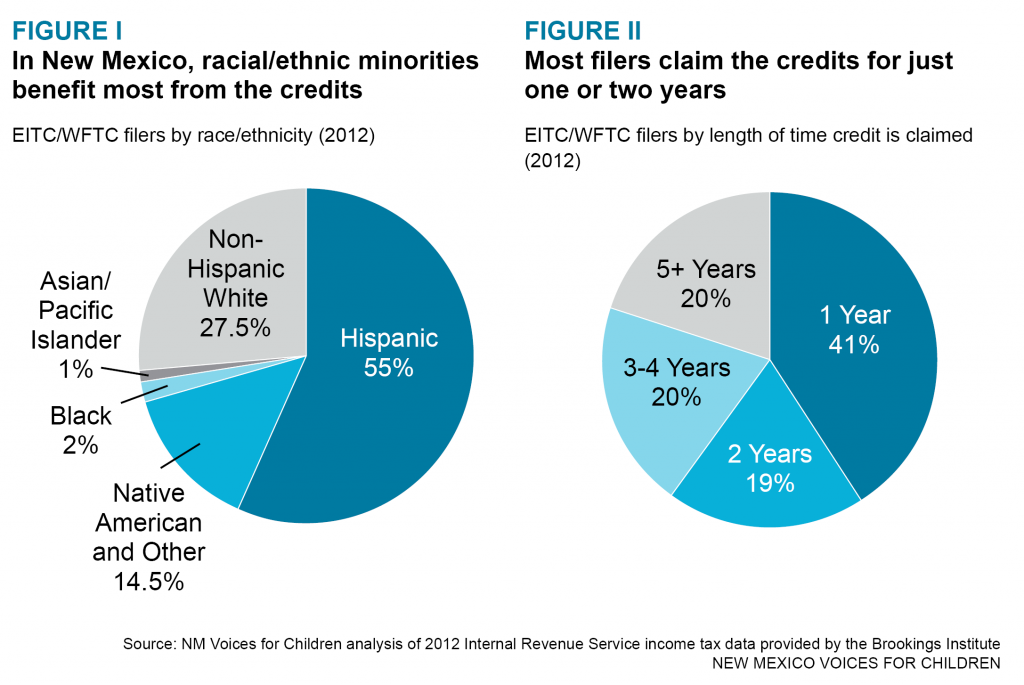

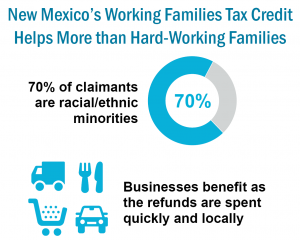

The majority of the more than 212,000 working New Mexicans who claim the EITC and WFTC every year are racial or ethnic minorities; 55 percent are Hispanic, nearly 15 percent are Native American, and 28 percent are non-Hispanic White (see Figure I). These filers have a median income of $13,638.3 The credits help most of these workers through tough but temporary economic troubles, such as a job loss or the birth of a child. In fact, three out of five workers claim the credits for only one or two years4 (See Figure II).

The vast majority of those who claim the EITC and WFTC are working, low-income parents who support the almost 300,000 kids living in the households that benefit from the credits. This is especially important, because according to the National KIDS COUNT program, New Mexico ranks 49th among the states in economic well-being, and 49th in overall child well-being.5 More than 97 percent of the EITC and WFTC money returned to taxpayers goes to working families. The income boost from the credits helps the families afford necessities like food, housing, and transportation. It also provides support for more than 14,000 New Mexico families headed by military veterans who are making their way back into the workforce.6

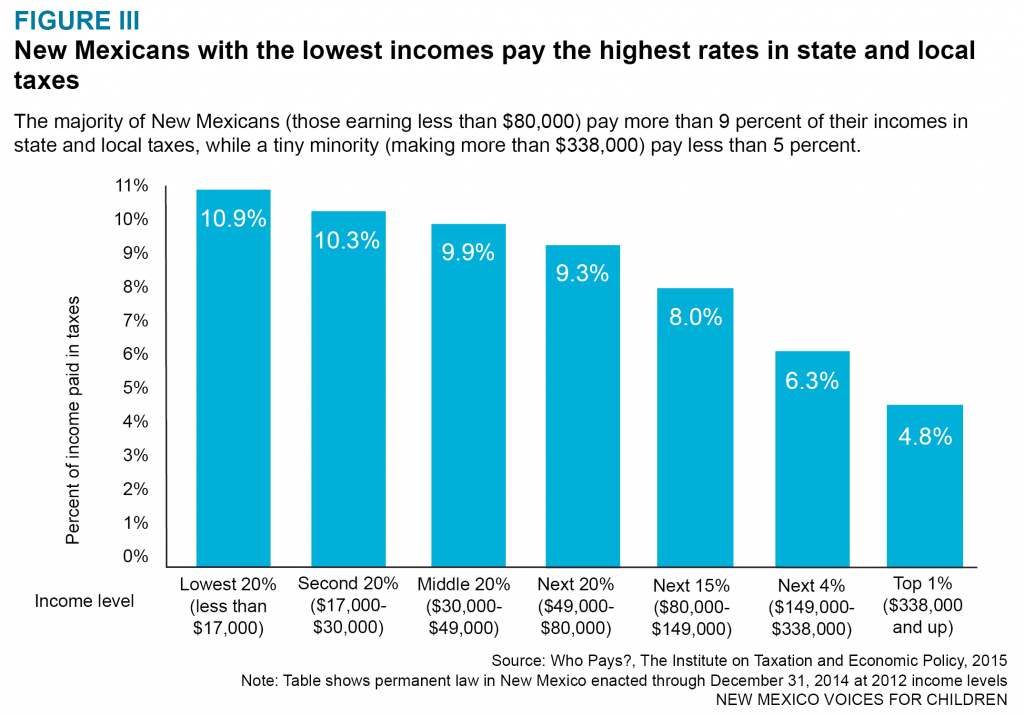

As a group, those who claim the EITC and WFTC pay a large percentage of their incomes in taxes. In fact, in addition to the federal payroll taxes they pay, New Mexico’s lowest-income households pay a greater share of their income in state and local taxes than do the highest-income households. Those making less than $17,000 a year pay more than 10 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes. Meanwhile, New Mexicans who make more than $300,000 pay less than 5 percent of their incomes in those same taxes7 (see Figure III). This huge disparity exists even after the current value of the EITC and WFTC are taken into account.

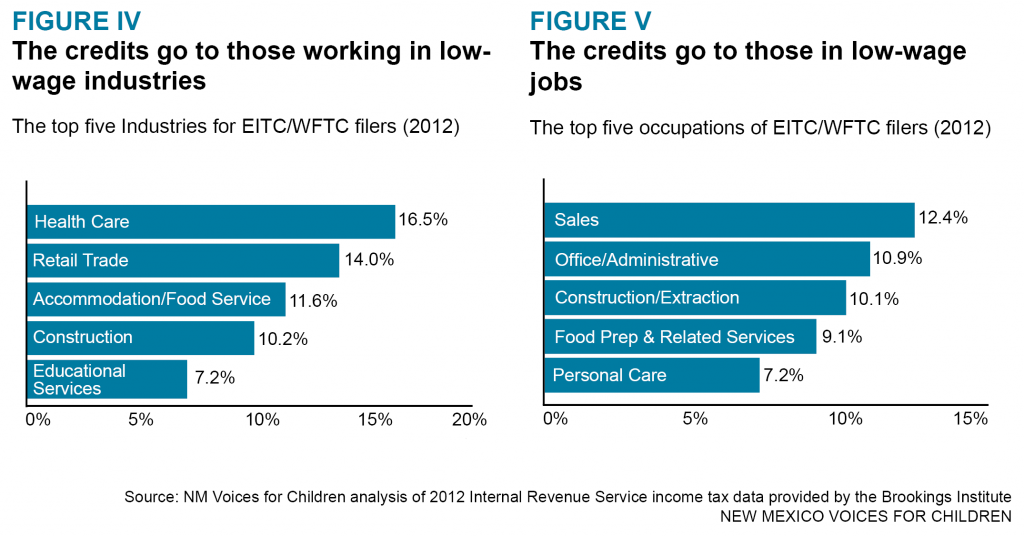

Many types of industries and occupations are represented among EITC/WFTC-eligible tax claimants (see Figure IV). The health care, retail trade, accommodation and food service, and construction sectors have the highest shares of workers who can claim the credits. The occupations that have the highest shares of EITC/WFTC filers are sales, office and administrative work, and construction and extraction (see Figure V).

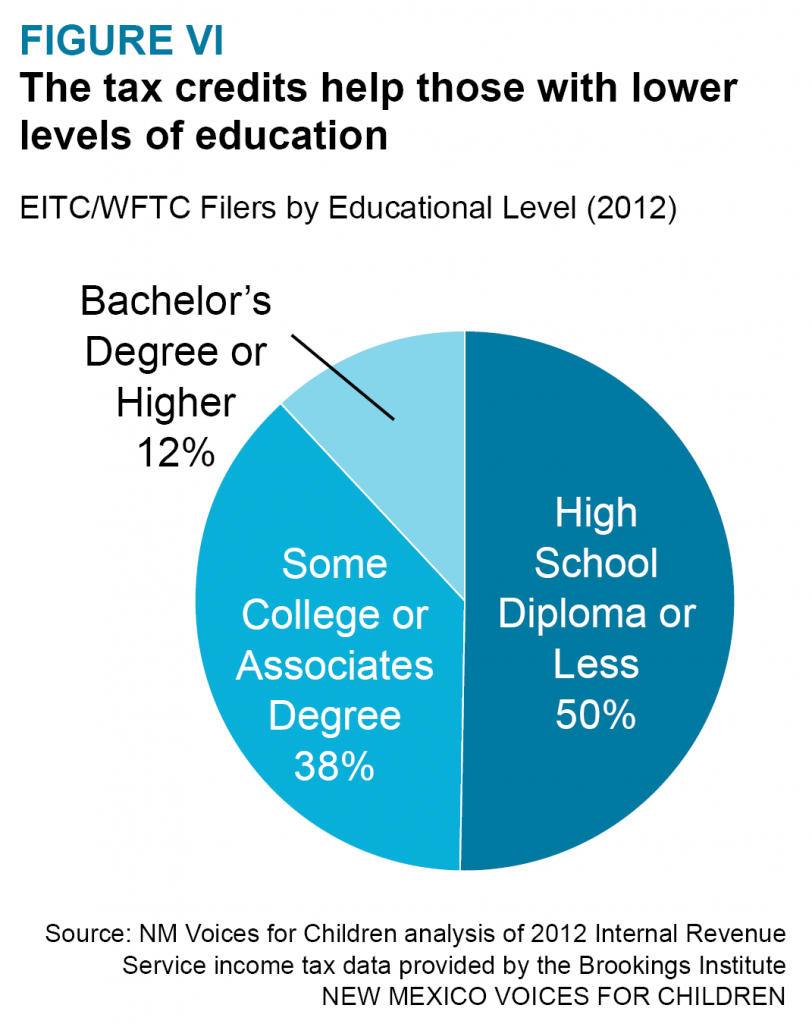

Half of filers have a high school diploma or less, but half have at least some college, with 12 percent of the filers having a bachelor’s degree or higher (see Figure VI).

Putting the Credits to Work for the State

New Mexico’s high rate of poverty would be even worse without these tax credits. Our overall poverty rate (22 percent) is among the highest in the nation and only one state has a higher rate of children in poverty (31 percent).8 New Mexico is one of just three states that saw an increase in poverty from 2012 to 2013.

New Mexico also has the highest percentage (44 percent) of working families that are low-income.9 Last year, the EITC and WFTC lifted more than 40,000 New Mexico families—including 20,000 children—out of poverty. New Mexico also has one of the highest rates of income inequality—meaning the gap between what the lowest-income New Mexicans earn and what the highest-income New Mexicans earn is among the largest in the nation. Income inequality puts our economy out of balance because too much income is concentrated into too few hands where it is less likely to be spent.

The WFTC is a relatively small investment on the part of the state that can make a big difference in the lives of working families. The extra income helps families to meet their kids’ basic needs, which in turn—research has shown—contributes to improved health outcomes,10 helps children perform better and go farther in school, and gives them a better chance to thrive and succeed as adults.11 And the effect is long-lasting. Because higher incomes from refundable tax credits are associated with better health, more education, and higher skills, children in EITC/WFTC families are more likely to work and earn more as adults.12

The EITC and WFTC also help low-income families participate in the workforce because they help pay for necessities like child care, transportation, and education or job training programs. This is good for businesses because workers who can pay for these basic needs are more reliable employees. Families with very low wages see higher refunds as their incomes rise, which encourages them to work more hours. Research shows that the EITC increases employment and reduces the need for public assistance.

The EITC and WFTC are also good for businesses because they are good for the state’s economy. Last year alone, New Mexico’s low-wage workers received nearly $550 million from the EITC and WFTC—the majority of which was pumped right back into the economy through rent payments, purchases of groceries and other household necessities, and to pay for child care. Research shows that EITC households spend their credits quickly and locally, so the credits have a strong multiplier effect. In fact, it is estimated that for every $1.00 claimed from the EITC, $1.50 to $2.00 is generated in local economic activity.13 That means the EITC alone is responsible for somewhere between $740 million and nearly $1 billion in economic activity in New Mexico each year.

Policy Recommendations

Evidence that New Mexico’s Working Families Tax Credit reduces poverty and spurs the economy is abundant. However, the credit could do even more with some small changes.

Increase the value of the WFTC. Lawmakers should increase the credit from 10 percent to at least 15 percent of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit. Efforts to do so in the 2014 session were very well supported. Raising the credit to 15 percent of the EITC would mean investing $25 million in our economy and our hard-working low-income families—a modest investment that will make a big difference for New Mexico families struggling to get by on low wages. At 10 percent, New Mexico’s WFTC is below the national average among other states that have a similar EITC-based tax credit.

Expand outreach efforts and tax preparation assistance. One in five eligible workers in New Mexico miss out on the EITC and WFTC, either because they don’t claim it when filing, or they don’t file a return. Tax assistance programs—such as the United Way and CNM’s Tax Help New Mexico program—that provide free (and bilingual) tax preparation for low-income New Mexicans are great models for tax preparation outreach. Lawmakers should expand outreach efforts like these and support free or low-cost tax preparation assistance in order to maximize the benefit of the credit.

Limit refund anticipation loans and checks. Another good reason for increasing access to free or low-cost tax preparation for low-income New Mexicans is that it keeps them from being preyed upon by commercial preparers offering refund anticipation loans (RALs) and refund anticipation checks (RACs). RALs are no-risk, very short-term loans made to the tax filer so they can receive a refund the same day. RACs are essentially the same thing except that a taxpayer must open a temporary bank account. Fees for preparation of the return and the RAC account are then deducted from the taxpayer’s refund before a check is issued to the taxpayer. Tax preparers who push RALs and RACs often fail to tell their customers that they could receive their refund by electronic transfer in as little as two weeks at no cost. Both RALs and RACs disproportionately harm EITC/WFTC tax filers and can syphon off much of the credits intended to help low-wage workers. New Mexico should limit the rate that can be charged on these refund options, mandate and standardize disclosure and marketing practices, and more strictly enforce compliance among lenders.

Endnotes

1 Quoted by Lea Donosky in “Sweeping Tax Overhaul Now The Law,” The Chicago Tribune, October 23, 1986

2 NM Voices for Children analysis of 2012 Internal Revenue Service (IRS) income tax data provided by the Brookings Institute

3 Ibid

4 Income Mobility and the Earned Income Tax Credit: Short-Term Safety Net or Long-Term Income Support, Tim Dowd and John B. Horowitz, 2011

5 KIDS COUNT Data Book, Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2014

6 Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of 2009-2012 American Community Survey data

7 Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2015

8 U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey data, 2013

9 Low-Income Working Families: The Growing Economic Gap, The Working Poor Families Project, analysis of U.S. Census American Community Survey 2011 data on families below 200% of the federal poverty level, 2013

10 The EITC: Linking Income to Real Health Outcomes, Hilary W. Hoynes, Douglas L. Miller, and David Simon, University of California Davis Center for Poverty Research, 2013

11 Earned Income Tax Credit Promotes Work, Encourages Children’s Success at School, Research Finds, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised in 2014

12 “Early-Childhood Poverty and Adult Attainment, Behavior, and Health,” Greg J. Duncan, Kathleen M. Ziol-Guest, and Ariel Kalil, Child Development, January/February 2010, pp. 306-325

13 Dollar Wise: The Best Practices on the Earned Income Tax Credit, U.S. Conference of Mayors, 2008