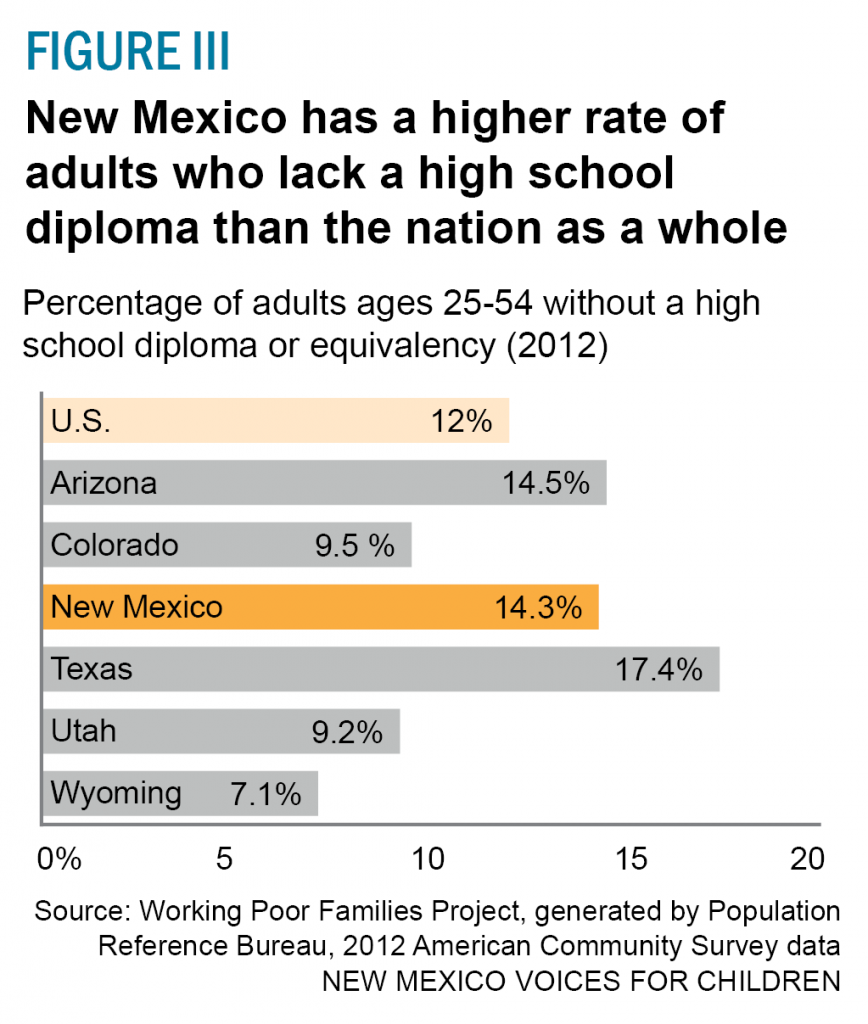

Link to the press release

by Gerard Bradley, MA

In the United States it has long been an article of faith—and economic statistics confirm it—that higher levels of education lead to higher incomes. Higher educational levels also lead to stronger communities and a better economy. We all benefit when young adults become doctors and nurses, engineers and chemists, teachers and first responders, or a whole host of other occupations that require a college degree or credential.

While higher education does lead to higher incomes, the converse is also true. Children from high-income families do better in school, are more likely to graduate high school, and go to college at significantly higher rates than do children from low-income families.1 There is more to this equation than money, of course. Whether children ultimately go on to college is also influenced by their parent’s own level of education, what kinds of enrichment opportunities were available to them, and many other factors.

Nationally, about 40 percent of adults have a college degree (associates or higher). In New Mexico, just 34 percent of adults have completed a college degree. Only nine states do worse. Not surprisingly, New Mexico’s income levels are lower than those in most other states. We also have a higher percentage of jobs that require little education and pay poverty-level wages, as well as a high poverty rate. Bottom line: the lower our percentage of degreed adults, the lower our percentage of doctors, teachers, engineers, and other well-paid professionals.

Considering the often symbiotic nature of income and education—and, on the other extreme, the cyclical nature of poverty—it is clear that states have an interest in ensuring that a college education is accessible to a broad swath of its population. After all, if all of our college graduates come from the same socio-economic stratosphere, we are clearly not tapping the potential of a vast segment of our population. But the high cost of college puts it out of the reach of too many New Mexicans. Even students who manage to attend college for a time, often need support in order to earn credentials or a degree. Students often cite the need to work and earn money as a major reason they drop out of college. Add to that the disparities in both education and income levels between Hispanics—the state’s largest ethnic group—and non-Hispanic whites, and New Mexico has a great deal to gain from making college more affordable for its residents.

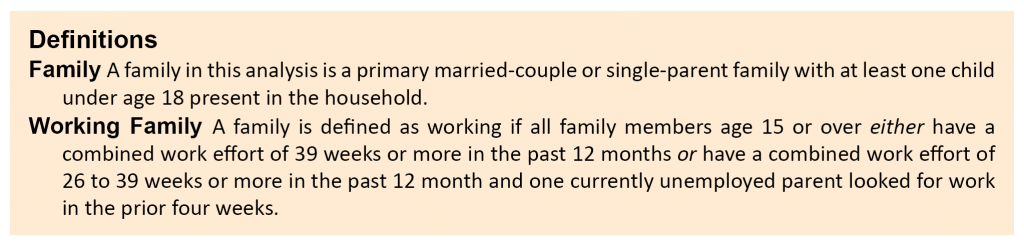

New Mexico has enacted a few policies to help make a college education more affordable, but as education data indicate, they have not been enough. Meanwhile, the state made some of the largest per-student spending cuts to higher education in the nation during the recession,2 New Mexico gives a significantly smaller share of its financial aid on a need-basis than the national average3 (see Figure I) and, perhaps most telling, despite leaving college with lower-than-average debt burdens, New Mexico students default on student loans at the highest rate in the nation.4

This report will show that current economic conditions facing low-income working families are such that these families have difficulty finding the resources to better their condition by obtaining a higher level of education, specifically through the community college system.

Helping with the Cost of College

In 1996 the state Legislature enacted the New Mexico Legislative Lottery Scholarship. The scholarship covers tuition at New Mexico universities for students attending college right after graduating from a New Mexico high school as long as they maintain a 2.5 grade point average. Students still have to cover fees, books, and living expenses. While the scholarship has undoubtedly allowed thousands of students attend college who would otherwise be unable, it is a merit-based scholarship, meaning any student who meets the academic and other criteria can receive it even if they could afford college without it. It also leaves out countless adults who wish to return to college after entering the workforce.

Demand for the Lottery Scholarship almost doubled from more than 10,000 students to more than 17,000 students from the spring semester of 2000 to the spring of 2010. During that same time, the total amount paid out in scholarships more than tripled from $8.8 million to $28.6 million per semester.

Due in part to this growing demand, as well as a leveling off of sales of lottery tickets and increases in tuition—which grew rapidly due to deep recession-era cuts in state funding—the balance of the Lottery Scholarship Trust Fund has been dwindling over the past several years. The fund was headed toward depletion when lawmakers changed the eligibility criteria in 2014. Rather than make the scholarship need-based, though, the Legislature limited the percentage of tuition the scholarship would cover, and required students at four-year universities to take a full-load of 15 credit hours per semester, up from the previous requirement of 12 hours. In essence, the changes have made it less helpful for low-income students—who now have to pick up part of the cost of tuition—and completely out-of-reach for students who cannot manage a 15-hour academic schedule because they also must work.

The College Affordability Fund was established in 2005 for students who lacked other financial resources or do not qualify for Lottery Scholarship assistance due to their age or academic standing. The fund had reached a high of $50 million prior to the recession, but was depleted to shore up other state spending.

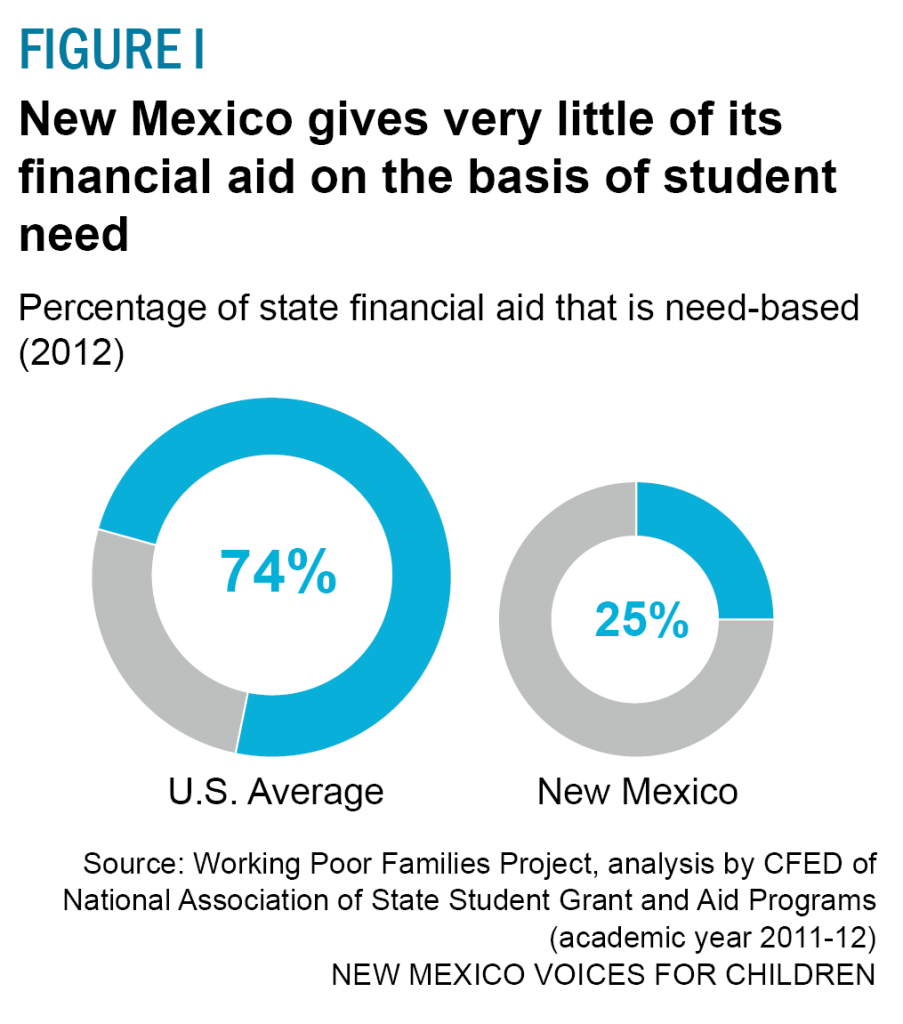

Although no money has been deposited into the College Affordability Fund in the past several years, the Higher Education Department (HED) has continued to provide about $2 million in need-based scholarships per year to roughly 3,500 students. Not only does the balance sheet for the fund (see Figure II) fail to indicate the source of this $2 million, it raises more questions about the viability of the fund than it answers. Staff members at HED were unresponsive when asked to provide an explanation.

An Educated Workforce: How New Mexico Stacks Up

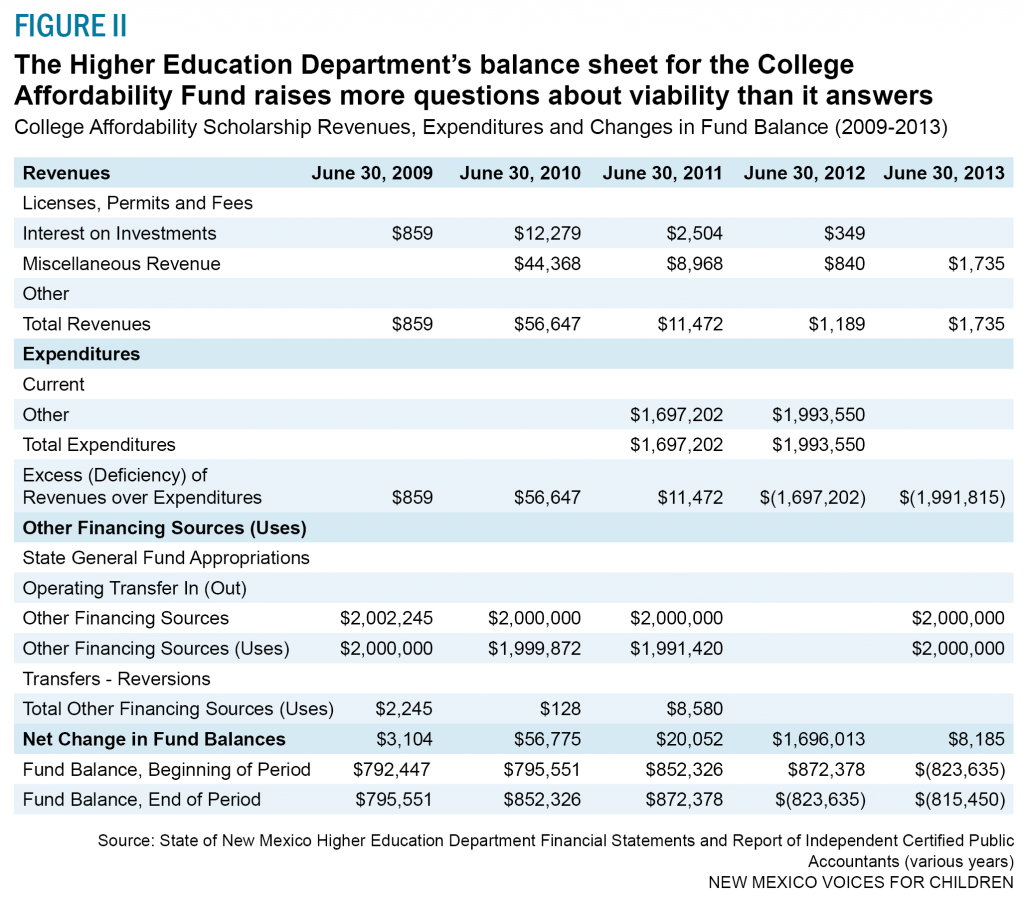

New Mexico does worse than the national average—and significantly worse than some of our surrounding states—when it comes to the educational levels of our adults aged 25 to 54. In this age group, 14 percent are without the most basic educational qualification—a high school diploma or equivalence—which ranks us 45th in the nation (see Figure III). Without a high school diploma, most workers are trapped in low-wage jobs that lack benefits and have no real hope of future advancement.

Of comparable surrounding states, which were selected for comparison because they have similar demographic or economic characteristics to New Mexico, Arizona and Texas do worse (in the case of 49th ranked Texas, considerably worse), but Colorado, Utah and Wyoming do significantly better than even the national average. New Mexico’s high percentage of adults without a high school diploma shows the need for more effort on the part of the state to reach working-age adults with adult basic education programs that lead to a certificate of high school equivalency.

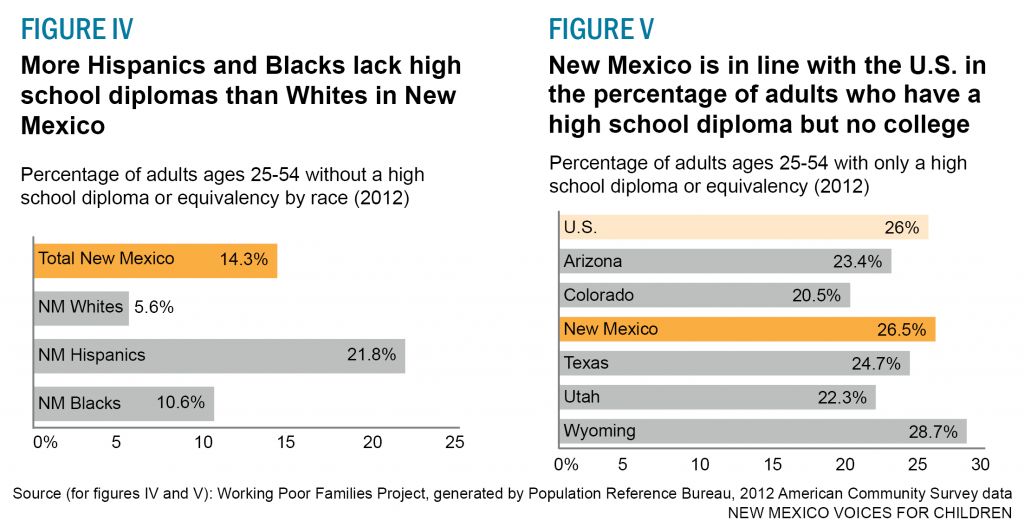

When these data are broken out by race/ethnicity, an even more troubling picture emerges (see Figure IV). While the problem is not negligible among non-Hispanic whites (with 6 percent lacking a high school diploma), it is clearly much more significant among all racial/ethnic minorities (20 percent), with Hispanics (22 percent) having the highest rate. One goal of educational policy for adults should be to narrow the gap between minorities, especially Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites.

In New Mexico, 27 percent of adults aged 25 to 54 have a high school diploma but no college (see Figure V). This is not much different from the national average of 26 percent and ranks New Mexico 22nd among the states by this measure. However, non-Hispanic whites perform well by this measure, as 19 percent of this group have only a high school diploma. Adults from all racial/ethnic minorities fare far worse, with 31 percent having only a high school diploma; 25 percent of African Americans and 31 percent of Hispanics have this minimal educational level.

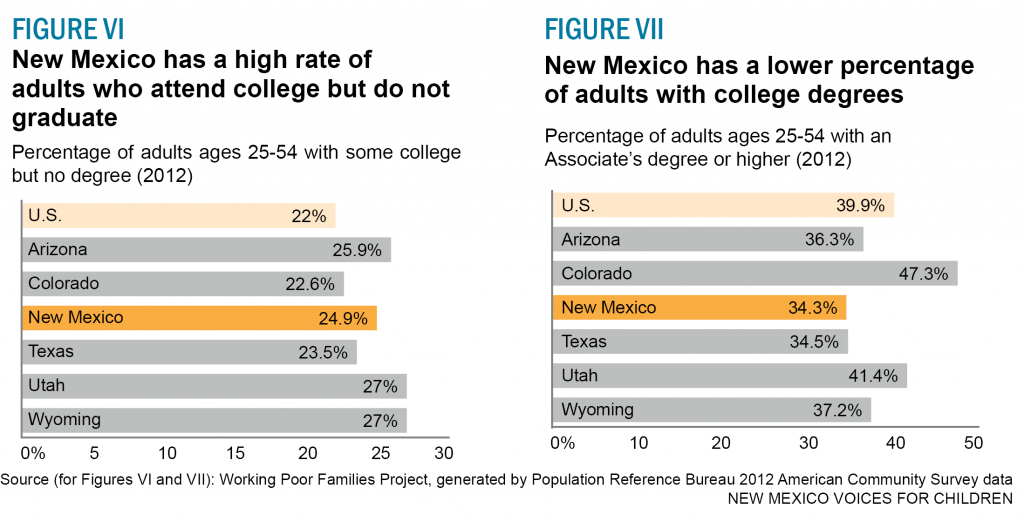

The rates improve when looking at New Mexico adults with some post-secondary education but no degree (see Figure VI). However, this is indicative of both success and underlying problems. Nearly 25 percent of adults ages 25 to 54 completed some post-secondary course work but failed to receive a degree, compared to 22 percent nationally. While completing any college course work is preferable to completing none, those who don’t receive a degree will earn less than those who do. Failure to complete the degree may be due to a number of causes including insufficient preparation for post-secondary course work, financial constraints, and family obligations. It may also account for some of New Mexico’s high rate of student loan default.

New Mexico’s non-Hispanic whites represent the highest percentage of these adults, with 26 percent completing some post-secondary coursework but not finishing a degree. The percentage for all minorities was 24 percent, for African Americans 24 percent, and for Hispanics 23 percent.

The fact that a quarter of New Mexico adults have some post-secondary coursework is a foundation for policy intervention that could improve the rate of completion of associate’s degrees and other credentials from community colleges. The fact that the percentage of racial/ethnic minorities with some post-secondary coursework approached that of non-Hispanic whites is especially encouraging. Making community college tuition-free, as the state of Tennessee recently did, would be a reasonable way of addressing this situation.

New Mexico has a ways to go to catch up with the rest of the nation in the percentage of adults who have an associate’s degree or higher (see Figure VII). New Mexico, with just slightly more than 34 percent of its adults earning degrees, is well below the national average of about 40 percent. The all-too familiar ethnic/racial disparities are especially telling in this case: 49 percent of non-Hispanic whites have an associate’s degree or higher, while only 25 percent of all minority adults and 24 percent of Hispanics earn degrees. Roughly twice as many non-Hispanic whites have a college degree compared with racial/ethnic minorities.

Our Working Families Struggle

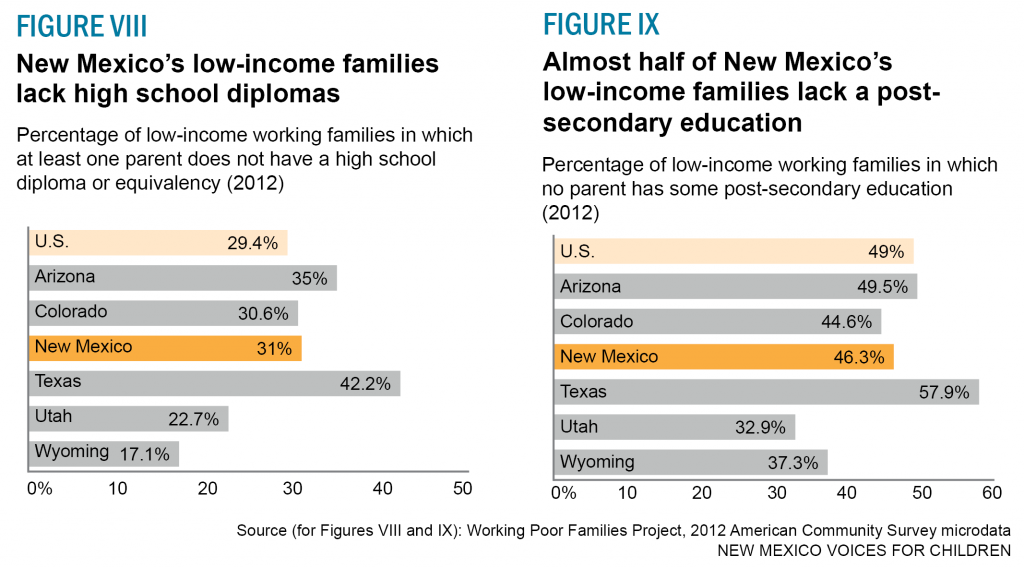

The numbers get worse when we look at the educational levels of low-income working families. A low-income family of four earned no more than $46,100 in 2012, or twice the federal poverty level. Almost one-third of New Mexico’s low-income working families have at least one parent without a high school diploma or equivalence (see Figure VIII). This is slightly higher than the national level of 29 percent. New Mexico ranks 45th lowest of all states by this measure. Of comparable states, Arizona (35 percent, ranking 47th) and Texas (42 percent, ranking 49th) do worse.

Low-income working families in New Mexico do slightly better than the national average when it comes to parents with some post-secondary education (see Figure IX). In New Mexico, 46 percent of low-income working families have no post-secondary education while the national average is 49 percent. New Mexico ranked 27th out of all states, though, far higher than Texas—with 58 percent and ranking 49th.

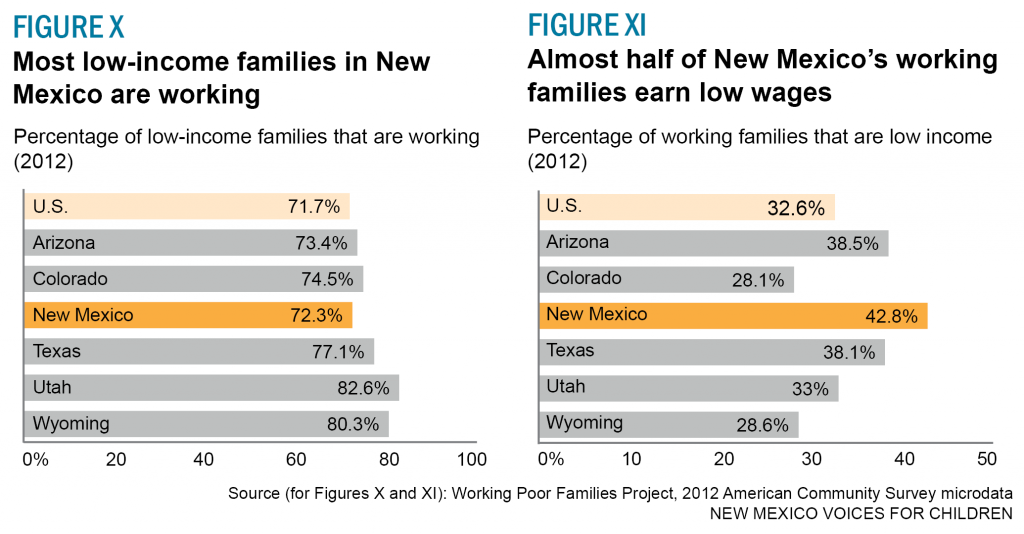

While New Mexico’s low-income families may have low levels of education, their adults are still out in the workforce, struggling to care for their children. In New Mexico, nearly three-quarters of low-income families are working families (see Figure X). The jobs held by members of these families typically pay low wages. Although the rate of low-income families that are working is higher in New Mexico than nationally, New Mexico had a lower percentage than comparable states in the region in 2012. Labor market conditions that year were better in Arizona, Colorado, Texas, Utah and Wyoming.

While Figure X shows the percentage of all low-income families that are working families, Figure XI shows the percentage of all working families that are low-income. This tells an even more dramatic story: nearly 43 percent of all working families in New Mexico earned an income below 200 percent of the poverty level in 2012. New Mexico’s rate is fully one-third higher than the national level of 33 percent and higher than all the states selected for comparison. New Mexico ranked 49th—or second worst in the nation—in terms of the percentage of working families getting by on bare-bones incomes. Clearly, working hard is not paying off for New Mexico’s families.

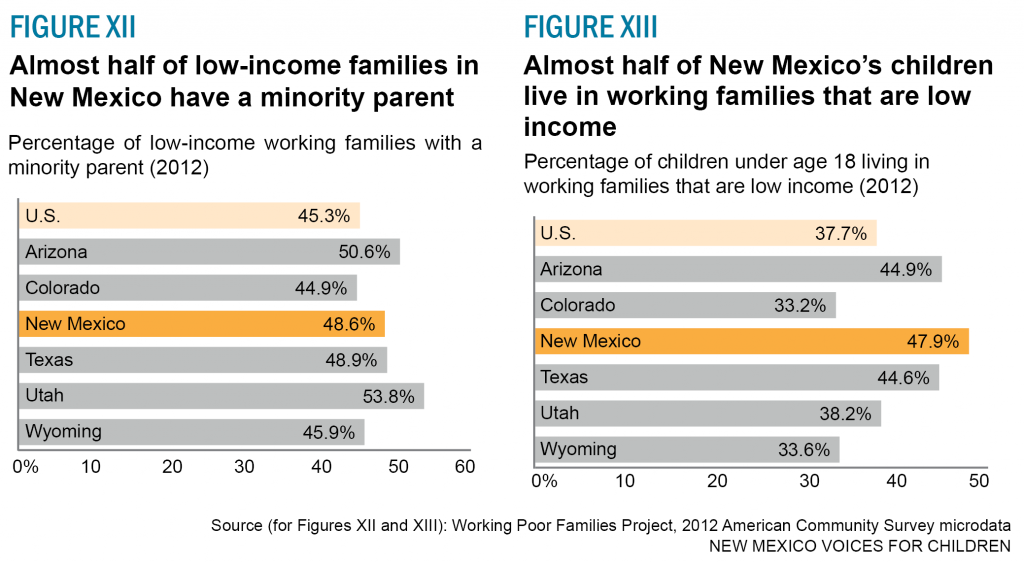

When race/ethnicity is taken into account, the picture darkens. More than 48 percent of New Mexico low-income families have at least one parent of a racial/ethnic minority group (see Figure XII)—a full three percentage points higher than the national average of 45 percent. Interestingly, Arizona (51 percent) and Utah (54 percent) had noticeably higher percentages than New Mexico. (They also have considerably smaller percentages of racial/ethnic minority adults: Just 18 percent of Utah’s and 38 percent of Arizona’s adult populations are non-white, while 56 percent of New Mexico’s is non-white.)

What should be of greatest concern to New Mexico policy makers is the high percentage of children living in low-income working families (see Figure XIII). Almost 48 percent of New Mexico’s children live in low-income working families. With nearly half of all children in low-income working families—far higher than the national average of 38 percent—New Mexico ranks 49th among the states. Even Arizona and Texas (both at 45 percent) perform better than New Mexico in this measure. Children living in low-income families are less likely than their middle- and high-income peers to do well in school, graduate, and attend college.

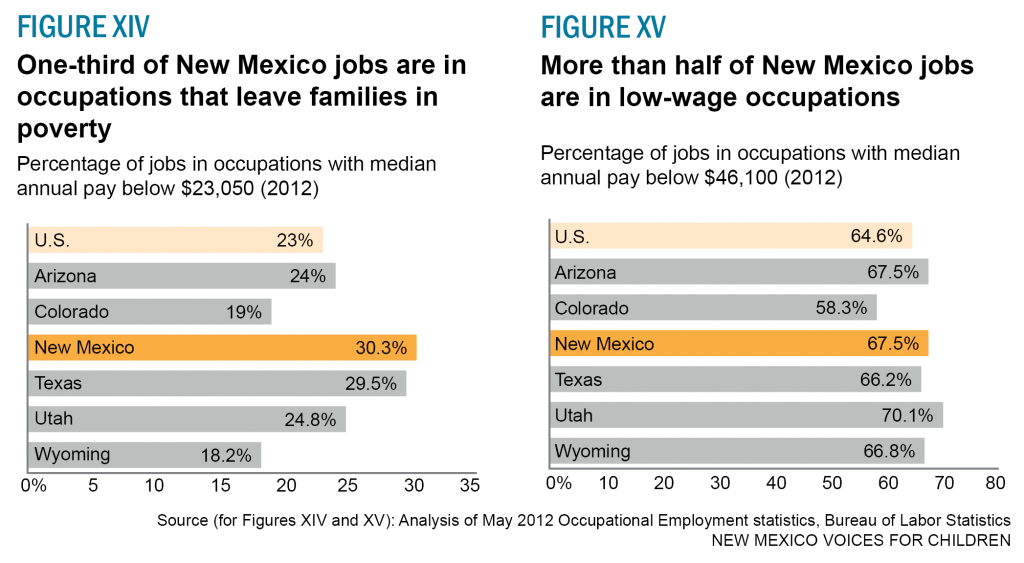

Not surprisingly, the demand for labor in New Mexico is heavily skewed toward low-wage occupations (see Figure XIV). In 2012, 30 percent of New Mexico jobs were in occupations that paid below the 2012 federal poverty threshold of $23,050 for a family of four. Even more distressing, fully two-thirds of New Mexico jobs were in occupations with a median annual pay below $46,100 for a family of four (see Figure XV).

At that income level, families do not earn enough for even a bare-bones standard of living (see Figure XVI). When families cannot even cover basic living necessities, they will have no way to pay for a college education.

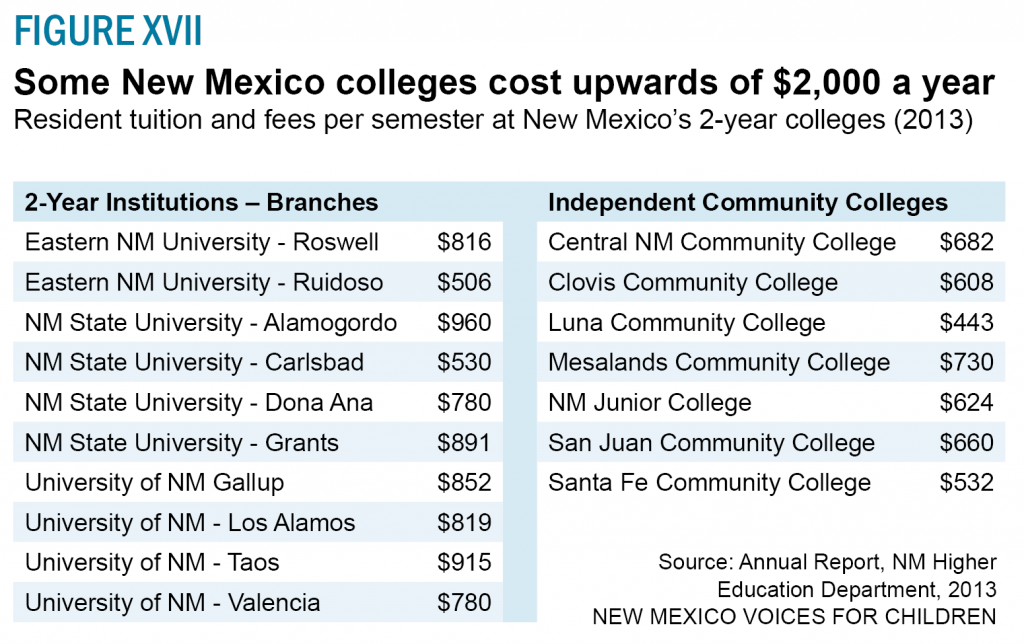

Given these economic realities, it’s clear that few low-income working families can afford two semesters of tuition per year, even at New Mexico’s relatively inexpensive community colleges (see Figure XVII).

Policy Recommendations

Restore money to the College Affordability Fund and expand eligibility. New Mexico should improve college affordability for low-income adults by providing significantly more state-funded, need-based financial aid. Restoring the currently empty College Affordability Fund would provide need-based tuition assistance to those who have been out of school for more than a year and may not qualify for merit scholarships. This fund should also be available to students taking less than a half-time course-load so non-traditional students can more easily fit school into their work schedules.

Develop a comprehensive career pathways framework. Some community colleges in New Mexico offer career pathways bridge programs like I-BEST (Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training) that help low-skilled adults gain high-demand post-secondary credentials by combining adult education with basic skills and technical instruction. The state should develop a comprehensive and statewide career pathways framework that better integrates and aligns adult education, bridge programs, and college courses to increase credential attainment and improve our workforce. States will soon have to focus more intently on career pathways when Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act regulations are released in the spring.

Provide integrated student support services including child care assistance. Student support services, including child care assistance, are an integral part of effective career pathways. Eligibility for child care assistance should be increased from the current 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) to the pre-recession 200 percent of FPL to help all low-income parents. Access to high-quality child care is an effective two-generation solution that provides early childhood education to young children while enabling parents to increase their education and earn marketable credentials. In studies of student parents taking classes at community colleges, researchers found that between 60 percent and 70 percent of respondents were dependent on child care services to continue their education.5

Make the Lottery Scholarship need-based. Given New Mexico’s high rate of poverty, making its flagship scholarship need-based is the most sensible course of action. There could be a complete shift to need-based criteria or a blending of merit-basis criteria with need-based criteria. The concept of a lottery scholarship based entirely on financial need could utilize the existing Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA).

Tap into unspent TANF funds. The federally funded TANF block grant is targeted to low-income parents and pregnant women to help them achieve economic self-sufficiency. Other states have effectively used TANF funds to pay for vocational training, post-secondary education, and child care assistance.6 In the past few years, New Mexico has rolled over millions of dollars of unspent TANF funds that could be used now to help low-income families earn credentials and weather the persistent economic downturn. Data show that about 10 percent of TANF recipients are enrolled in education and/or training in New Mexico (the national average is 9 percent).7 New Mexico should follow the lead of Oklahoma and Georgia, which rank at the top of that category by enrolling more than 30 percent of their TANF recipients in education and training programs.

Endnotes

1 “Real Analysis of Real Education,” Anthony Carnevale, Liberal Education, Volume 94, Number 4, 2008

2 Recent Deep State Higher Education Cuts May Harm Students and the Economy for Years to Come, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2013

3 State Higher Education Finance: FY 2011, State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO)

4 Student Debt and the Class of 2014, U.S. Department of Education, 2014

5 Improving Child Care Access to Promote Postsecondary Success Among Low-Income Parents, Miller et al., Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 2011.

6 Funding Career Pathways and Career Pathways Bridges: A Federal Funding Tool Kit for States, Center for Postsecondary and Economic Success at CLASP, 2013.

7 Working Poor Families Project analysis of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2011 data

The Working Poor Families Project is funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Ford Foundation, Joyce Foundation, and The Kresge Foundation.