Download this policy brief (June 2021; 12 pages; pdf)

By Emily Wildau, MPP

June 2021

With special thanks to several individuals and organizations for reviewing and offering feedback for this publication, including Patricia Jiménez-Latham, Mary Parr-Sanchez, and Charles Goodmacher.

Introduction

New Mexico is unique, with a diversity of geographies, languages, histories, and cultures that is unmatched in the nation. These should be key components of a high-quality public education system that meets the needs of all of our children, each of whom have great potential to strengthen our schools with their unique perspectives while succeeding academically. However, while we know that our kids, our diversity, and our schools are assets for New Mexico’s communities, the state has not effectively grown and nurtured these strengths. Instead, New Mexico has too frequently allowed our education system to offer uneven support to our students, with a particular lack of attention to the ways our K-12 schools are unable to meet the needs of children, families, and communities of color and children from working families earning low incomes.

As a state, we’ve not always adequately provided the funding schools need to deliver high-quality, comprehensive education and support services to all New Mexico students. Too frequently in the past, policymakers have given costly tax breaks to corporations and the well-connected that starved our state of much-needed education revenue and resources. As 25% of our kids live in poverty,[1] it’s important to note that it’s estimated it costs at least 40% more to educate a student in poverty to the same standards as a more affluent student[2] due to the additional stress and trauma related to childhood poverty.

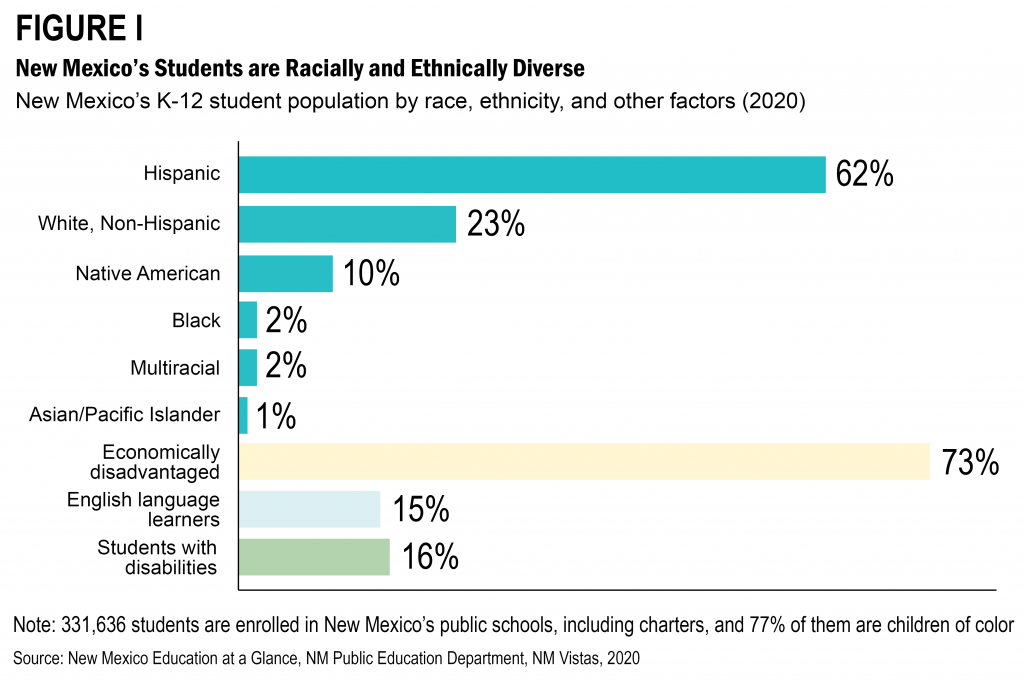

Yet, the state has not enacted sufficient revenue-raising measures to provide the additional funding to educate children in low-resource communities and families. In 2022, voters will have the opportunity to pass a constitutional amendment that will increase funding distributions for K-12 schools from the Land Grant Permanent Fund. Although helpful, this would be insufficient to solve the state’s significant education funding shortfalls. Additionally, many students of color do not see themselves or their cultures represented in the curricula. The result is a school system that fails to provide the resources necessary for too many children in the state, particularly the more than three-quarters of students who are children of color, as well as those who have disabilities, are English language learners, and are from families earning low incomes (see Figure I). This historical lack of education funding has robbed too many New Mexico kids of the opportunities to reach their full potential and left our kids behind the national rates for reading and math proficiency and graduation, with greater gaps along racial lines and by income levels.

In 2018, the consolidated Yazzie/Martinez lawsuit ruling agreed that insufficient funding was tied to poor educational outcomes for the majority of students, and that a lack of revenue was no excuse to deprive students of their constitutional right to a sufficient and uniform education. Since then, New Mexico has been moving in the right direction to increase targeted funding for the students our education system has not supported well, but the pandemic and recession have put the state’s educational progress at risk. Lawmakers must continue investing in our children so public school outcomes reflect the strength and potential of all New Mexico students.

New Mexico’s K-12 Education Landscape

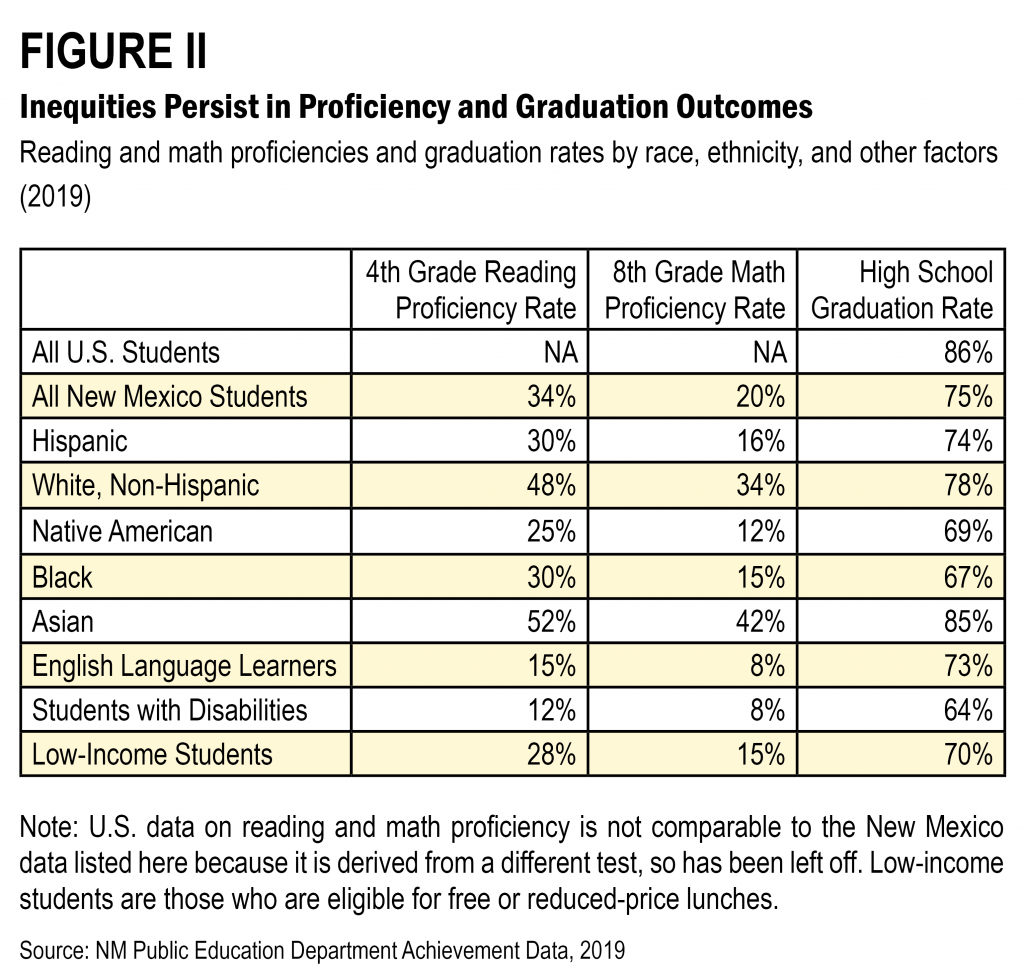

In 2020, and for the fourth year in a row, the Annie E. Casey Foundation ranked New Mexico 50th in the nation in education.[3] Students identified as “at-risk” in the Yazzie/Martinez ruling are more likely to face challenges when it comes to proficiency and graduation rates. Disparate outcomes by race and ethnicity, language, ability, and income[4] (see Figure II) are related to two key challenges that New Mexico’s public education system faces: a shortage of funding for evidence-based programs, curricula, and support services that would provide all students with the opportunities needed to succeed, and a shortage of teachers and other educational support staff like educational assistants, nurses, physical and occupational therapists, and speech-language pathologists.

Funding Landscape and Shortage

Funding for public schools is complex and includes state, local, and federal funding sources. The intent of this brief is to provide a broad overview of some of New Mexico’s key school funding streams. Any funding topics not covered are beyond the scope of this brief. New Mexico public schools are primarily funded by the state, with nearly half of the state’s annual budget allocated to K-12 education.[5] In some ways, our school funding is more equitable than the funding systems used in most other states. While most states rely heavily on property taxes for funding schools – resulting in the wealthiest neighborhoods receiving the most school funding – New Mexico shifted primary funding to the state level in 1974 by establishing the State Equalization Guarantee (SEG) funding formula in the Public School Finance Act.[6] At the time, the SEG was considered one of most innovative school finance plans nationally, and New Mexico is still one of just three “equalized states,” with a formula that determines district-level funding based on the characteristics of the students enrolled, not the location of the school and the property taxes each can raise. As a result, property taxes make up a small percentage of school funding in New Mexico. In 1997, the “at-risk” index was adopted so districts with more low-income students, English learners, and migratory students would receive additional funding based on federal Title I data.[7]

Although the SEG makes New Mexico’s public school funding formula more equitable than the funding structures in most other states, it’s not perfect. Currently, the SEG allocations do not sufficiently address the needs of students in very high-poverty districts – as the highest poverty districts only receive 2% to 3% more funding per student than does the average district,[8] nowhere near the 40% more needed to educate children in poverty. Also, the funding goes to districts, and prior to 2021 the SEG had no mechanism to account for the sometimes-extreme variation in poverty levels between individual schools within a district. This likely resulted in funding disparities when local school boards allocated funds to individual schools if some schools had a significantly higher proportion of low-income students than did others in the district.

New Mexico public schools also receive a small amount of federal funding that is designed to help cover the costs of educating students who are economically disadvantaged. Title I funding was created with the passage of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 1965 and amended in the No Child Left Behind and Every Student Succeeds Acts. This funding is designated to improve the academic achievement of students in high-poverty schools who have had less opportunity to succeed in school due to current and historical systemic racism. Funding is allocated to districts by determining the number of low-income students served. The vast majority – 87% – of New Mexico’s public and charter schools receive Title I funding to help low-income students succeed regardless of barriers they may face as a result of poverty.[9] Additionally, public schools receive Title III funding for English language learners. New Mexico schools also receive funding to participate in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) to provide free and reduced-price lunches to students who might otherwise not have enough to eat. Fully 63% of our students qualify for this program,[10] which is often used as a proxy to identify the number of students who are low-income in a school.

Two other forms of federal funding are particularly relevant to New Mexico’s education funding landscape. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires states to provide a free, appropriate public education for all students with physical and intellectual disabilities. Funding is included in the IDEA, and it has helped to improve outcomes for students with disabilities since its passage in 1975. However, the IDEA falls significantly short of what it originally promised: the federal government is responsible for 40% of states’ additional costs to educate students with disabilities, but it has maintained a national average funding level of just 13%. In 2020, New Mexico footed the bill for 84% of special education costs from our general fund, while federal IDEA funding accounted for 16%.[11] Because schools are required to provide the services students with disabilities need without regard to cost, the underfunding of IDEA creates an annual funding gap in educating and supporting this group of students.

Federal Impact Aid goes directly to qualifying districts to make up for the funding that is lost locally because federal land and tribal areas are exempt from property taxes. But, since New Mexico is recognized as having “equalized” state funding, the state has been able to “take credit” for a portion of the Impact Aid payments in order to reduce the SEG distribution going to those districts.[12] There have been several challenges to the state’s practice of taking credit for Impact Aid, with the most recent asserting that New Mexico should no longer qualify as an equalized state in light of the Yazzie/Martinez ruling.[13] During the 2021 legislative session, policymakers passed a bill that will end this practice starting in the 2021-2022 school year.

Educator Shortage

In addition to schools lacking outright funding, New Mexico also struggles to hire and retain enough teachers and educational support staff to fully deliver the education our kids are guaranteed in the constitution, along with the wrap-around services many of them need in order to succeed. As of September 2020, our state had 889 educator vacancies, with 571 of those vacancies being teachers. Of the teacher vacancies, 152 are for special education teachers.[14] With 88 districts, 889 vacancies would average about ten vacancies per district. However, not all districts have the same number of schools and those with the highest concentration of low-income students are likely to have more inexperienced teachers because turnover rates tend to be higher.

One of the reasons New Mexico struggles to fill educator vacancies is the so-called “wage penalty” associated with teaching in public schools. Although benefits make up for some of the wage penalty, New Mexico teachers earn a weekly wage that is almost 30% lower than what other comparable college-educated workers earn. This is the third highest wage penalty for teachers nationwide.[15]

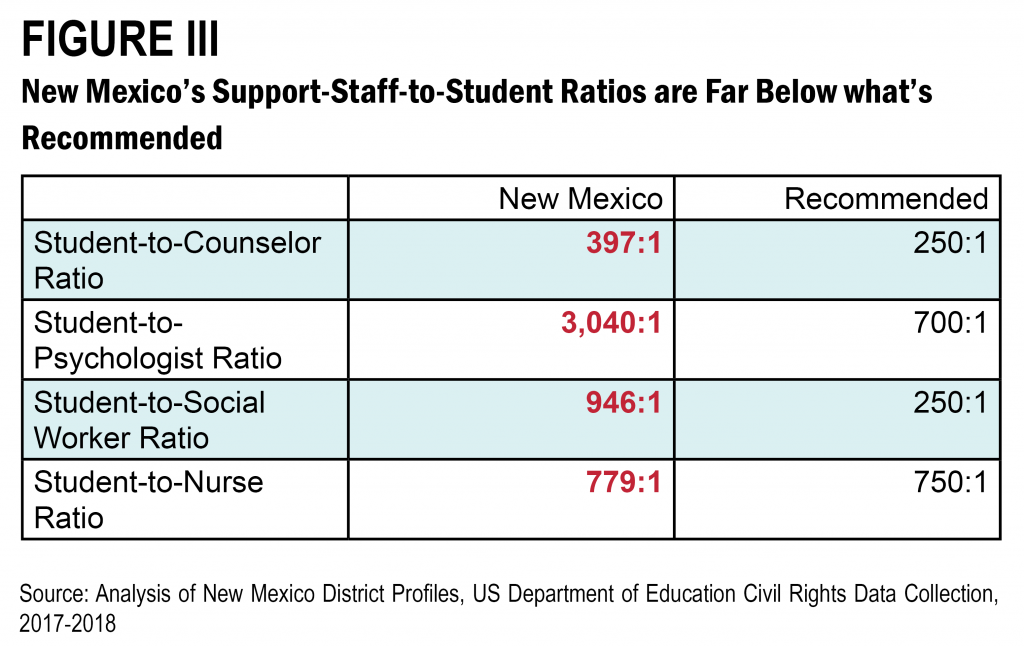

It’s not just a challenge to fill teaching positions; except for nurses, New Mexico schools are not meeting recommended staff ratios for student mental and behavioral health services, which more students are likely to need during and after the COVID-19 pandemic[16] (see Figure III). Combined with these challenges, the number of vacancies may grow as a result of the pandemic, with older teachers leaving due to health concerns. There is also a possibility that districts will simply close unfilled positions to balance budgets, resulting in fewer vacancies but more long-term teacher shortages that are likely to disproportionately impact schools with higher numbers of students of color and in low-income communities.[17]

COVID-19’s Impact on Education

Every school district developed a unique response to COVID-19, with a variety of instructional plans designed to shift with public health orders throughout the 2020-2021 school year. From at least March 2020 to March 2021, students attending schools receiving federal Title I funding were less likely to receive in-person education than students attending non-Title I schools, which has almost certainly compounded existing opportunity and achievement gaps.[18] Students experienced up to a year of unfinished learning as a result of emergency school closures and the transition to remote learning at the end of the 2019-2020 school year. It is estimated that they lost another three to 14 months in the first half of the 2020-2021 school year as schools largely remained online.[19] Teachers report that they were unable to reach one in five of their students while one in three did not participate in the fall 2020 semester.[20]

By the end of the fall semester, districts saw significant decreases in enrollment that are largely tied to the pandemic. Official attendance reports from October 2020 indicated more than 12,000 students previously enrolled in New Mexico’s public schools could not be accounted for or contacted, although the NM Public Education Department (NMPED) had located all but 2,522 of these students in the spring semester.[21] Of the located students, half had either enrolled in private schools or moved out of state, and this lower enrollment could be permanent – causing a decrease in funding for school districts during the 2021-2022 school year.[22]

Although 80% of elementary school students were in districts eligible to resume in-person learning at some point during the fall semester, only 34% of those students were in districts that chose to return to physical classrooms. It is unclear, however, how many of those students actually received in-person instruction versus opting to remain in a virtual setting.[23] During remote learning, students with disabilities have been especially likely to lose opportunities for academic and social-emotional progress without easy access to one-to-one, in-person education support services. Although allowances are in place to provide in-person learning for students with disabilities as long as remote learning continues, districts have provided this option to students unevenly.[24] The state recently required districts to offer in-person learning to all students, although it is too soon for an analysis of how many students chose to receive in-person instruction and how many remained in remote learning for the remainder of the 2020-2021 school year.

Throughout the pandemic, there have also been many concerns regarding students’ social-emotional well-being and the uncertainty many families are facing in acquiring basic needs. Teachers report that 36% of their students are experiencing social-emotional issues or require social-emotional health supports.[25] New Mexico has also seen a dramatic drop in child abuse reports, which is partly the result of remote learning, since teachers and other school staff are often the first to identify and report signs of child abuse.[26] Initially, it was feared that student suicides and suicide attempts would increase – a big concern as our state already had one of the highest rates of youth suicide in the nation.[27] Although the mental health of some students has certainly been impacted, it does not appear that the shift to online learning has driven an increase in the rate of youth suicide. To ensure that the risk of abuse and suicide do not increase as a result of the pandemic, it is critical that districts receive the necessary funding to increase social-emotional and mental health supports and that the state funds a more robust mental health system overall to support the well-being of students and their families.

While data on child well-being during the pandemic is spotty, the U.S. Census Bureau has conducted its Household Pulse Survey weekly or biweekly since March of 2020 to determine the real-time impact of COVID-19. In New Mexico, 15% of adults in households with children report that the children are not getting enough to eat because the family can’t afford food.[28] Most districts opted to utilize a NSLP waiver allowing schools to provide free meals for pick-up or delivery for all students through June of 2021, regardless of their eligibility for the free and reduced-price lunch program. Pandemic EBT for families, a federal relief program designed to provide additional food for children during school closures, was also extended until at least June 2021.[29] Internet access is also a problem, as 8% of New Mexican adults in households with school-aged children reported that they sometimes, rarely, or never have internet access, according to the Household Pulse Survey.[30] Since this survey was completed online, it is likely underestimating household lack of internet access. A state survey found 22% of students did not have internet access at home, with 55% of students in Bureau of Indian Education schools lacking internet access.[31] The Yazzie/Martinez plaintiffs submitted a motion to the courts to address this well-documented lack of internet access, and on April 30, 2021, the judge ordered the state to immediately provide “at-risk” students with a dedicated device and high-speed internet access.[32]

During the first 2020 special legislative session, policymakers cut FY21 funding by 1% ($146 million) for K-12 schools and the SEG distribution.[33] In preparation for the 2021 legislative session, all state agencies were asked to cut their FY22 budget requests by 5%, although the Governor’s budget request to the Legislature ultimately resulted in a flat budget due to more optimistic revenue forecasts than previously expected.[34] The request notably included a hold harmless policy for pandemic-related decreases in enrollment, an end to the Impact Aid credit, and a Family Income Index to provide a more equitable formula than the “at-risk” index currently offers by establishing an income metric to calculate economic disadvantage at the school level.[35] Given the legislation passed to end the practice of taking credit for Impact Aid and to pilot the Family Income Index, the budget for public schools ultimately represented an increase of 5.5% over the FY21 budget after cuts, with a 7.5% increase for the SEG distribution. When comparing the FY22 budget to the original FY21 budget, there was actually a slight decrease for school funding overall and an increase of 1.2% for the SEG distribution. However, the state is also receiving $979 million for K-12 schools through the American Rescue Plan, with the majority going directly to districts.[36] At this time, it is also unclear how districts will allocate these funds.

Why We Should Protect K-12 Funding

The recession and decreased oil and gas revenues, while less severe than originally anticipated, have led to economic uncertainty, and too many lawmakers cited this uncertainty as justification to oppose bills that would have increased education spending in response to the Yazzie/Martinez lawsuit during the 2021 legislative session. Although we applaud lawmakers for avoiding the austerity measures of the past, they could have taken bolder steps to invest in New Mexico students and our future. The pandemic has meant that New Mexico students need support now more than ever, not only in their education, but through the many additional resources provided to kids and families by our public schools.

Providing enough funding to sufficiently educate our kids, many of whom are from low-income families and communities, is a challenge even in the best of circumstances. Over the past three legislative sessions, our lawmakers have begun to increase the state’s investment in public education with a significant focus on our students from low-income families, students of color, English language learners, and students with disabilities, but the work to equitably educate all of our students is far from over. To achieve our goal of providing every New Mexico child with a high-quality education that provides them with the technical and academic skills they need to thrive, lawmakers must continue to provide the necessary funding to improve educational opportunities for all of New Mexico’s students.

Policy Recommendations to Strengthen K-12 Education in New Mexico

Protect and Increase Investments

- Develop concrete, long-term, comprehensive plans for equitable and sufficient education, with an adequate investment of state funding and resources, for all New Mexico students, particularly those student groups identified in the Yazzie/Martinez lawsuit, by working with the Transform Education New Mexico coalition, Tribes and their education departments, and the Tribal Education Alliance relying on the Tribal Remedy Framework created and developed by tribal communities and Indigenous education experts.

- Identify reliable and adequate funding streams for public schools.

- Continue increasing state investments in our students, our schools, and our teachers, with particular focus on investments designed to promote tribal, bilingual, and multicultural education, as well as pathways for teachers and school staff who reflect our student population.

- Support new approaches like the Family Income Index so funding is better targeted to schools with students from families earning the very lowest incomes to help these students succeed.

- Advocate for Congress to fully fund the IDEA to better support our students with disabilities.

Respond to COVID-19 with Racial and Socio-Economic Equity Lenses

- Braid or blend federal and state funding to improve broadband connectivity for rural and tribal communities.

- Increase funding for and implementation of more community schools and school-based health centers to support the increased number of students and families with additional needs as a result of the pandemic.

- Request the extension of waivers that allow schools to continue to provide meals for all students through the 2021-2022 school year.

Address Unfinished Learning and Social-Emotional Needs

- Dedicate funding to increase the number of social workers, teachers, nurses, psychologists, and counselors so students have a full network of support during and after the pandemic, as well as rebuild our state’s mental and behavioral health system.

- Encourage districts to extend the school year through participation in Extended Learning Time Programs and K-5 Plus to mitigate unfinished learning.

- Conduct non-punitive student assessments designed to help teachers meet students where they are.

Endnotes

[1] Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months, Table S1701, American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, US Census Bureau, 2019

[2] “Funding Gaps: An analysis of school funding equity across the US and within each state,” The Education Trust, 2018

[3] Population Reference Bureau data, analysis of data gathered for the 2017 to 2020 KIDS COUNT Data Books, KIDS COUNT Data Center, Annie E Casey Foundation

[4] New Mexico Public Education Department (PED) Achievement Data, 2019

[5] “Legislating for Results: Post-Session Review,” NM Legislative Finance Committee (LFC), April 2020

[6] “How New Mexico Public Schools are Funded,” NM PED, April 2016

[7] “Alternative Methods for Including At-Risk Students in the At-Risk Index,” NM Legislative Education Study Committee (LESC), Nov. 5, 2020

[8] “Public School Support and Public Education Department FY22 Budget Requests,” NM PED presentation to NM LFC, Dec. 9, 2020

[9] CCD Public School Data, National Center for Education Statistics, 2018-19 & 2019-20 school years

[10] State Level Tables: FY2015-2019, National School Lunch Participation, USDA Child Nutrition Tables

[11] “Serving Students with Disabilities in New Mexico: Challenges and Potential Solutions,” NM LESC, August 24, 2020

[12] “Impact Aid and New Mexico’s Funding Formula: FY20 and FY21,” NM LESC, Aug. 24, 2020

[13] Ibid

[14] “2020 NM Educator Vacancy Report,” NMSU Southwest Outreach Academic Research Evaluation and Policy Center, Oct. 6, 2020

[15] “Teacher pay penalty dips but persists in 2019,” Economic Policy Institute, Sept. 17, 2020

[16] Analysis of New Mexico District Profiles, US Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection, 2017-2018

[17] Reducing District Budgets Responsibly, Annenberg Institute at Brown University’s EdResearch for Recovery series

[18] “Status of School Reopening and Remote Education in Fall 2020,” NM LFC, Oct. 28, 2020

[19] Ibid

[20] Ibid

[21] “List of Unaccounted-For Students Shrinks to Under 3,000: PED, Partners Further Whittle Original List of 12,186 Student,” NM PED news release, Dec. 30, 2020

[22] NM School Superintendents Association presentation to the NM LESC, Sept. 23, 2020

[23] “Status of School Reopening and Remote Education in Fall 2020,” NM LFC, 2020

[24] Ibid

[25] Ibid

[26] “The Impact of COVID-19 on Child Well-Being in New Mexico,” NM Voices for Children, August 2020

[27] “Teen Suicide in New Mexico,” America’s Health Rankings, January 2021

[28] “Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, data from March 2021

[29] New Mexico: COVID-19 Waivers & Flexibilities, Food and Nutrition Service, US Department of Agriculture

[30] New Mexico COVID-19 Education Indicator, KIDS COUNT Data Center, Annie E. Casey Foundation

[31] “Learning Loss Due to COVID-19 Pandemic,” NM LFC, June 10, 2020

[32] “Court orders state to provide students the technology they need,” NM Center on Law and Poverty news release, April 2021.

[33] “2020 Special Session Budget Summary,” NM Voices for Children, July 2020

[34] Appropriation Request Instructions for FY22, NM Department of Finance and Administration, as of September 2020

[35] NM PED FY22 Budget Request presentation to the LFC, Dec. 9, 2020

[36] “An Unparalleled Investment in U.S. Public Education: Analysis of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021,” Learning Policy Institute, March 2021