Download this report (Oct. 2011; 8 pages; pdf)

Introduction

by Gerry Bradley, MA

Like most of the 50 states, New Mexico’s revenue fell sharply as the Great Recession took hold. New Mexico’s leaders began addressing the revenue shortfall in 2009 by cutting state spending and making up the difference with federal revenues from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). In the case of New Mexico’s public school system, this resulted in delaying budget cuts until the 2011-12 school year.

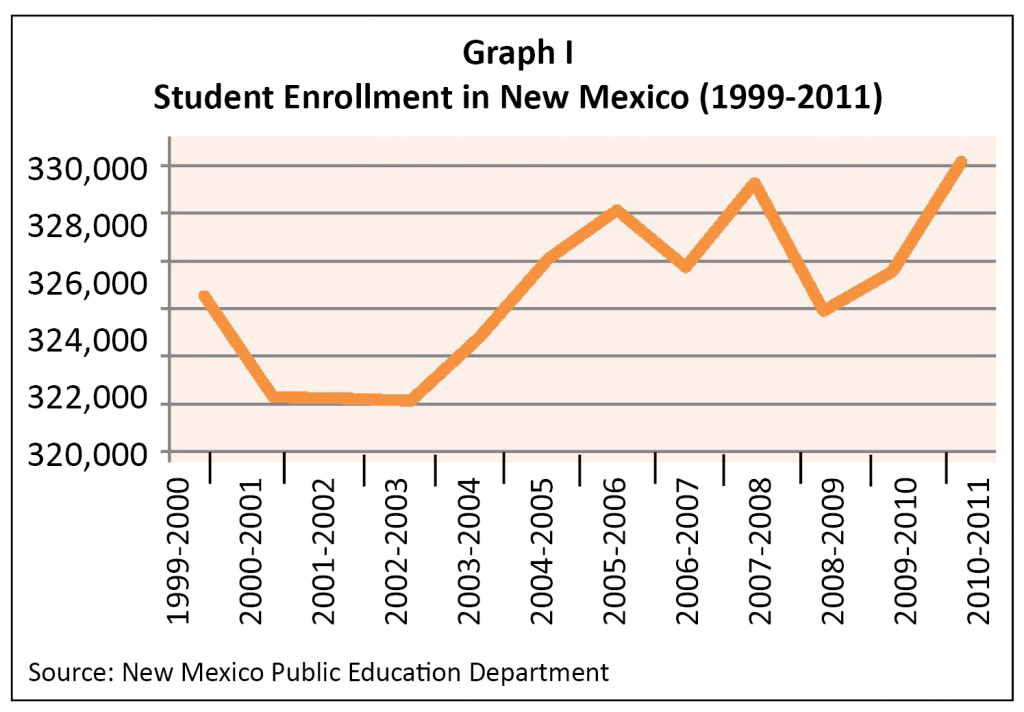

Education accounts for the single largest expenditure from the state general fund budget, with public K-12 school accounting for 44.6 percent of all state general fund expenditures in fiscal year 2011 (FY11). Public school expenditures from the general fund declined by 1.4 percent from FY11 to FY12, but the public school budget as a whole saw a drop of 5.1 percent due to the loss of federal stimulus funds. This led to a loss of some 2,300 education sector jobs between September 2010 and September 2011—a 5 percent decline. The loss of funding and personnel came in the face of student enrollment growth and inflation, both of which drive up costs. Student enrollment has increased in the last three school years, after falling slightly in 2006-07 and 2007-08 (see Graph I).

The State Equalization Guarantee

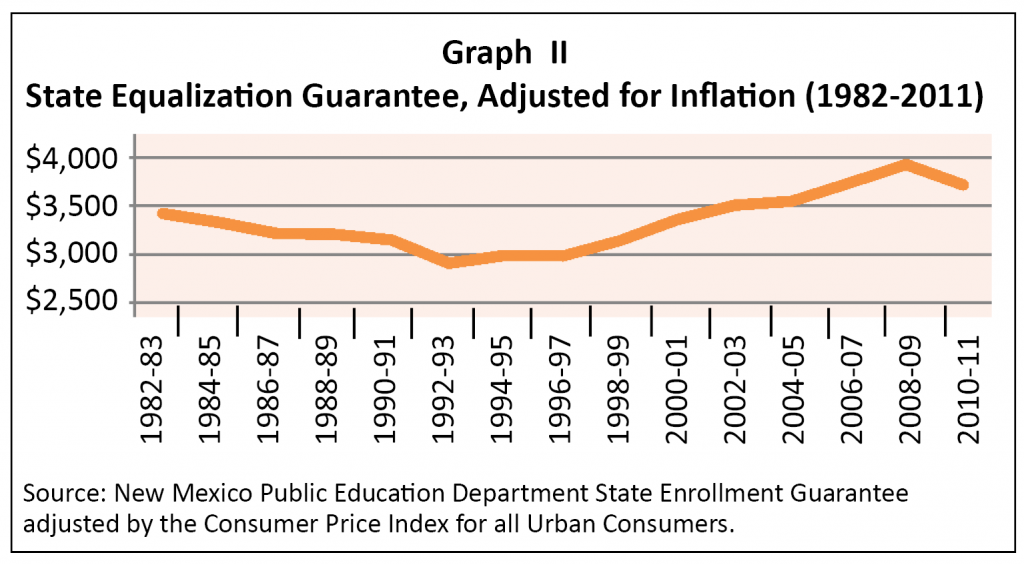

The primary mechanism for allocating funds to the state’s public schools is called the state equalization guarantee (SEG). The SEG is the amount allocated to each district by the state Public Education Department (PED) for each student. Graph II shows the SEG from 1982 to 2011, adjusted for inflation as measured by the Consumer Price index for all Urban Consumers (CPI-U). In inflation-adjusted dollars, the SEG showed a smooth upward trend for the past 30 years until the 2008-09 fiscal year. Because of the recession, the Legislature reduced the SEG in real terms for the first time in more than a decade.

Trends in Public School Funding During the Recession

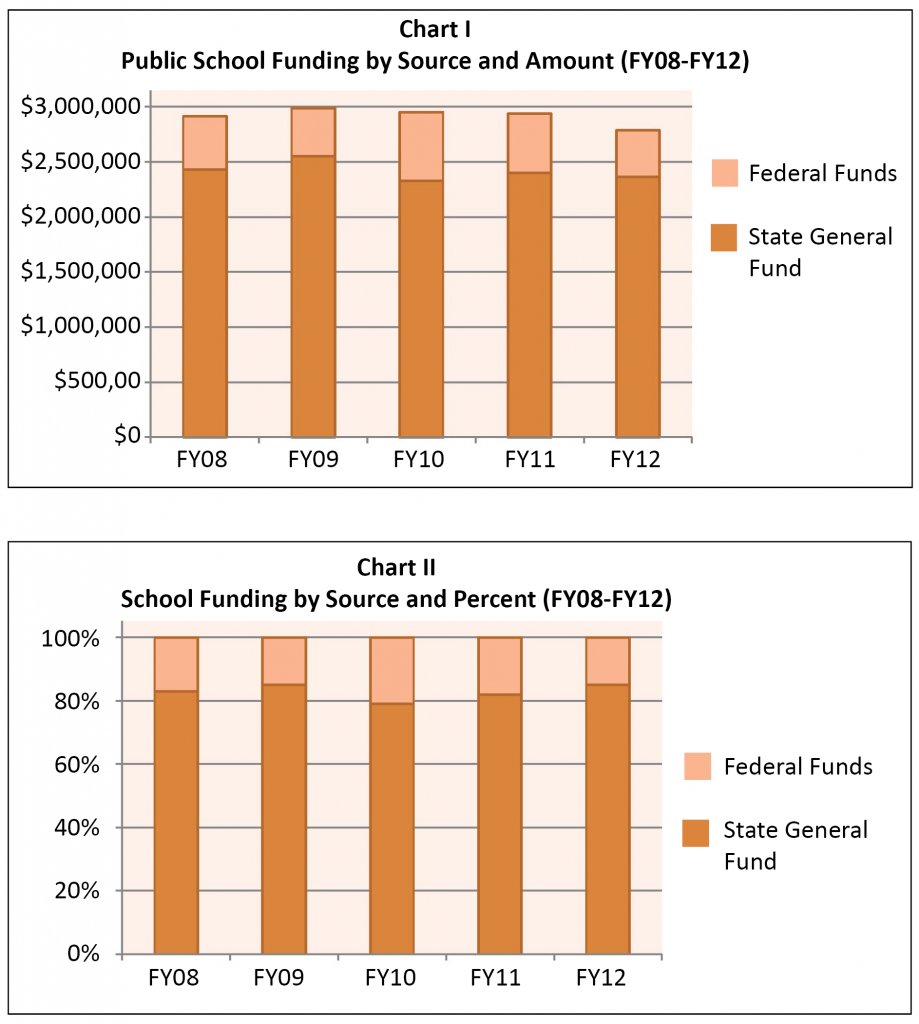

New Mexico’s method of paying for public schools is much more centralized than in most other states. In New Mexico, the largest portion of funding—nearly 85 percent in FY12—comes from the state general fund, which relies heavily on income and sales taxes. Charts I and II show that while revenues from income and sales taxes declined precipitously during fiscal years 2010 and 2011, federal funds increased to compensate.

New Mexico receives a higher share of federal revenues for education than most states. Generally, the federal government contributes about 15 percent of the overall public school budget. But, due to the recession, the federal contribution to the public school budget went up to 21 percent in FY10. It moved downward to more typical levels near 15 percent in FY12 even though the state budget had not recovered to its pre-recession levels.

In most states, property tax revenues are used to pay for the operating costs of the schools. That is not the case in New Mexico. In New Mexico, property taxes are used for public school building construction and upkeep, with just very small shares going to operating costs. (Property taxes are not included in the two bar charts because the amounts were too small to show up at this scale.) Our lack of reliance on property taxes did not help matters during the recession. Property taxes tend to be “sticky” in a recession—meaning they remain somewhat stable even when home prices fall. That’s because property assessments typically lag behind the decline in property values. Also, even when the foreclosure rate rises, as it did during the recession, property tax revenues don’t necessarily fall—the lender is still responsible for the property tax on the foreclosed property. Income and sales taxes, on the other hand, fall during a recession.

The Land Grant Permanent Fund

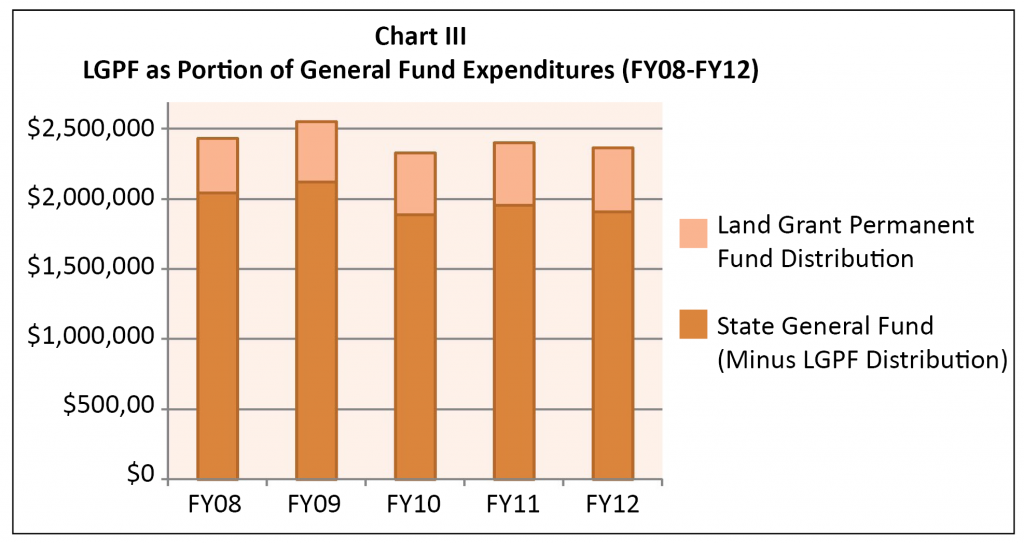

The state general fund includes ‘earmarked’ revenues from the Land Grant Permanent Fund LGPF). New Mexico’s LGPF is the second highest in the nation, at about $10 billion. Money distributed from the LGPF comes mainly from interest income earned from investing the corpus, although the Fund does have other sources of income (largely royalties from mining activities and the extraction of oil and natural gas). In FY12 about $460 million (or roughly one-fifth) of the total $2.366 billion general fund spending on public education came from the LGPF (see Chart III). This was way up from FY08, when the distribution was about $390 million—which indicates the rebound in investment income since the 2007 stock market crash.

The amount distributed from the LGPF varies by year according to the balance of the Fund, but the percentage (normally 5 percent) is based on a formula that is laid out in the state constitution. In 2003, New Mexico voters approved a set of increments in addition to the base distribution of 5 percent. Between fiscal years 2005 and 2012, public education had been receiving an additional increment of 0.8 percent on top of the constitutional base distribution of 5 percent. Between fiscal years 2013 and 2016 public education will receive a reduced additional increment of 0.5 percent. This 0.3 percent reduction will cost the public schools $30 million. The increment will end in FY17. If the distribution from the LGPF is allowed to expire, it would cost the public education system $50 million (assuming the LGPF balance stays at about $10 billion).

The FY11 Education Operating Budget

The FY11 Education Operating Budget

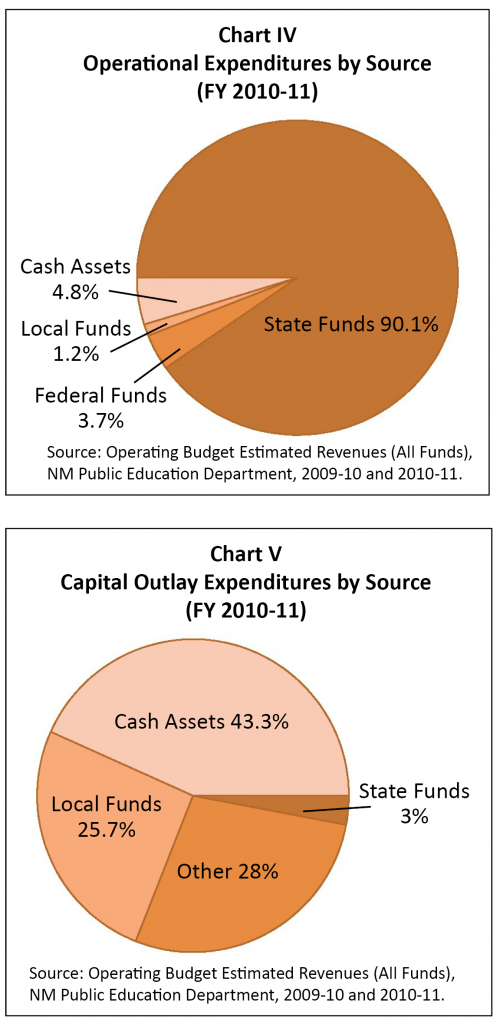

Public school expenditures are broken out by type—operating, capital outlay, special projects, and debt service. Operating expenditures are the costs of keeping the schools open and the school employees paid. About 90 percent of public school operating expenditures were covered by the state general fund in the 2010-11 operating budget. (Fiscal year 2012 numbers were not available at the time of this writing.) Federal funds and cash assets carried over from the previous year accounted for most of the rest (see Chart IV).

Capital spending pays for the building of new and upkeep of existing school buildings. This funding comes from local funds and ‘other’ funding, which is mainly from the property tax (see Chart V). A significant share of property tax revenues come from increments approved by voters for school building, upkeep, and repairs.

State funding accounted for about half of the total of all public school expenditures. Local funding and federal funds were about 12 percent each. Cash assets carried over from the previous year were almost one-fifth of total budgeted expenditures (see Chart VI).

When looking at total expenditures by type, operational expenditures were almost 55 percent. Capital projects were about 25 percent, special projects an eighth of the total, and debt service almost a tenth (see Chart VII).

Conclusion

State general fund expenditures for public education fell slightly in FY12: dropping by $34.1 million (or 1.4 percent) from $2.399 billion in FY11 to $2.365 billion in FY12. Federal expenditures, however, saw a drastic decline of 5.1 percent in FY12. State policy-makers were unable or unwilling to make up this shortfall with new revenues. Lawmakers could have enacted a wide variety of tax measures that would not have harmed the state economy but would have kept the public school budget from falling. The upshot of the failure to enact tax increases was that employment in the state’s K-12 education sector fell lost 2,300 jobs between September 2010 and September 2011 for a drop of 5 percent.

The total funding drop from FY11 to FY12 means public schools are being forced to do more with 5 percent less funding. The 5 percent drop in public education employment will result in increased class sizes and an erosion of the quality of education in the public schools. Meanwhile, enrollment in public schools is rising, as are prices. This means that public schools are facing extreme resource constraints.

Policy Recommendations

The most recent set of revenue estimates from the New Mexico state government (released on October 18, 2011) project that the state’s economy will continue to recover slowly. However, if revenues don’t increase substantially, lawmakers should raise additional sources of revenue rather than continue to under-fund education. Revenues could be increased by raising income tax rates on high-income taxpayers without harming the recovery because high-income earners tend to save a large share of their income. Savings are effectively a withdrawal of purchasing power from the economy, while income that is spent contributes to the demand for goods and services, helping the economy and encouraging investment.

One of the obstacles that public education faces is that many of the children who enter public education at the kindergarten level are not prepared to begin school. To its credit, New Mexico started a statewide pre-kindergarten program in 2004, but the program is not universally available and is far from fully funded. Numerous studies have shown that significant brain development is concentrated in the earliest years of life, years when exposure to high-quality early care and education programs can have the most impact.

A broad coalition of advocates for early care and education has emerged in New Mexico over the past two years. That coalition—including faith-based groups, child advocates such as New Mexico Voices for Children, the labor movement, and some far-sighted elements of the business community—endorsed a proposal to amend the New Mexico constitution to provide a additional distribution of 2 percentage points from the LGPF, most of which would have funded a comprehensive program of early care and education in New Mexico. This continuum of services would include coaching and education for first-time parents, high-quality child care programs, and voluntary but universally available pre-kindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds. The Legislature should pass a resolution during the 2012 session so that a constitutional amendment can be on the ballot in the 2012 general election.

Finally, there has been much criticism of public education here in New Mexico, as well as nationally. Richard Rothstein of the Teachers College of Columbia University examined the issue of school performance in 2004. The thesis of his book, Class and Schools, which is based on a broad review of education literature, is that the main predictor of the success or failure of a school or of a school system is the pervasiveness of poverty in that community. Poverty has only grown worse since 2004, thanks to the recession. Although the subject is too vast to address here, the greatest contributor to school success would be a full-employment economy with strong demand for workers and plentiful jobs. That would reduce poverty and contribute to educational success.

Download this report (Oct. 2011; 8 pages; pdf)

The Fiscal Policy Project, a program of New Mexico Voices for Children, is made possible by grants from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the McCune Charitable Foundation, and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.