Executive Summary

Executive Summary

Download this executive summary (April 2014; 2 pages; pdf)

Download the full report (12 pages; pdf)

Link to the press release

by Gerry Bradley, M.A.

The complete elimination of the corporate income tax as a meaningful revenue source for the state of New Mexico appears, unfortunately, to be within sight. Making significant changes to the corporate income tax (CIT) structure has been popular with state leaders of late. A bill that makes corporate net operating losses deductible for twenty years was passed in the recently concluded 2014 legislative session and signed into law. An omnibus tax bill that made several changes to the state’s CIT code was enacted in 2013. Both bills are expected to lower tax revenue collections.

The reasoning behind recent CIT legislation was to encourage economic development. In general, however, the academic literature is skeptical about the efficacy of using the tax system for such purposes.

CIT and the States

The existence of a corporate income tax is a fairly typical part of a state’s tax system. All but four states tax the net income of the corporations earning profits there. In 2009, the U.S. Census Bureau found that corporate income taxes accounted for some $40 billion in state government revenues.

There are several rationales for the corporate income tax, the most common of which is the benefit principle. Because corporations benefit from having transportation infrastructure, an educated workforce, and public safety services, corporations should help pay the costs.

When corporations aren’t required to pay their share of taxes to support these services, either individuals end up paying more to make up the difference or those services are cut. Cutting such services is likely to end up hindering a state’s ability to entice new businesses and keep existing ones.

A Small but Crucial Role

The CIT plays a small—but crucial—role in New Mexico’s revenue structure. The CIT accounted for just 4.6 percent of the state’s revenues in FY12 and FY13, rising very slightly to 4.8 percent as the economic recovery gained a little steam in FY14.

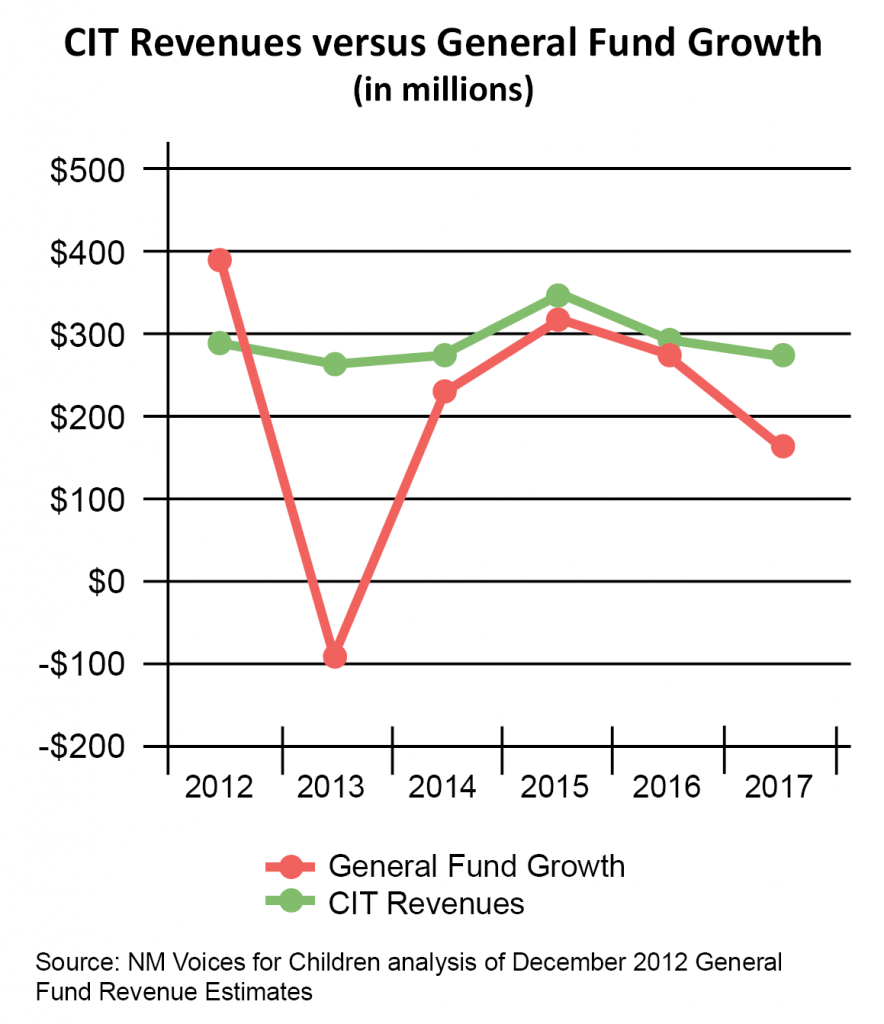

Some forms of taxation are more stable than others—meaning they fluctuate less over time. As the line graph on page 2 shows, the growth of CIT revenues has been very stable compared to the erratic growth of the general fund as a whole. The annual growth in general fund revenues has been quite unstable in recent years and will continue to be choppy in the near future. That the CIT helps to stabilize general fund revenues is a feature that policy-makers should be aware of when thinking about making more changes to this revenue source.

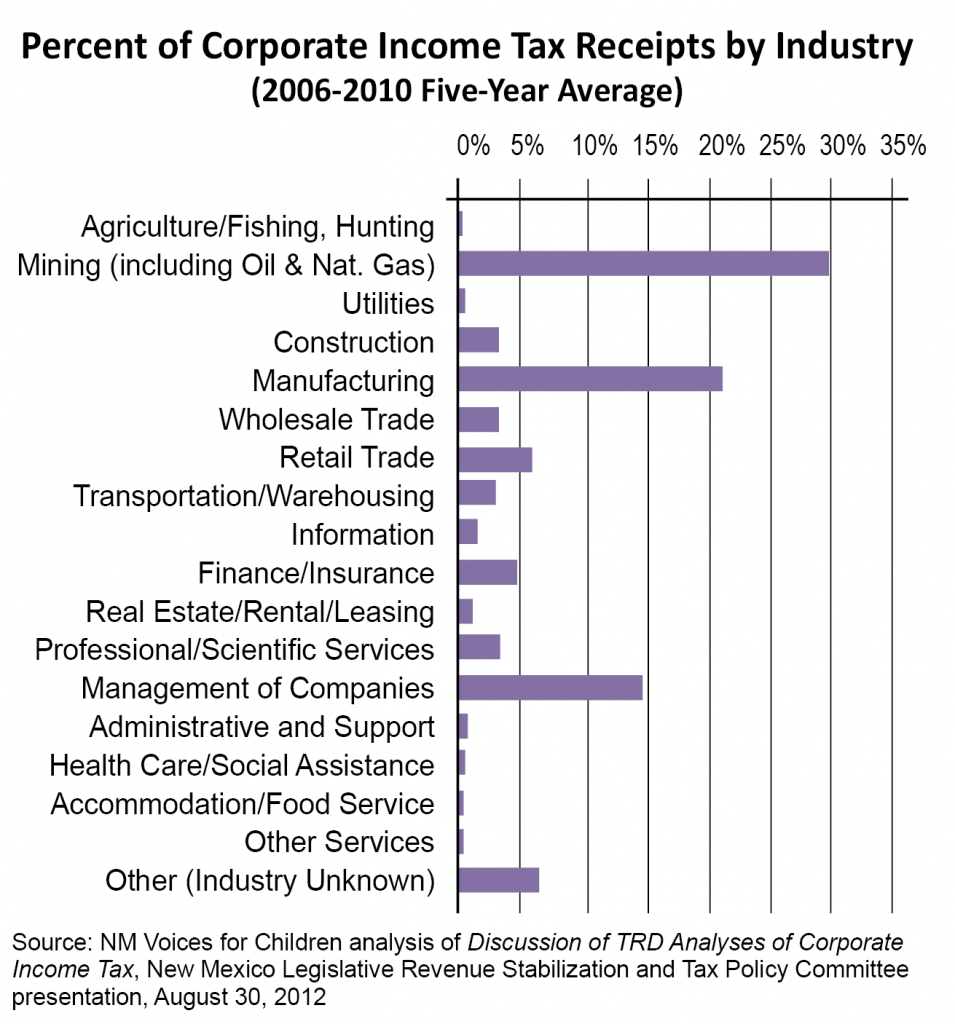

The CIT in New Mexico is paid largely by the mining, manufacturing, and management of companies sectors, with those three sectors accounting for about two-thirds of corporate income tax receipts.

In general, the tax for multi-state corporations is determined by three factors—the company’s payroll, property, and sales in the state—in proportion to the corporation’s total income.

About 30 percent of CIT paid in New Mexico comes from the property factor, 40 percent from the sales factor, and 30 percent from the payroll factor. In 2013, however, the apportionment method was changed for manufacturing. By 2018 the manufacturing sector will be allowed to apportion solely based on sales in New Mexico. This change is a real boon to manufacturers that may have a large payroll and property holdings here but sell most of what they make in other parts of the country.

The 2013 legislation also reduced the CIT rate from 7.6 percent to 5.9 percent in stages, with a complete reduction taking place in 2018. The revenue lost from these two changes to the CIT were initially expected to be $111.6 million in FY17, according to the fiscal impact report.

For many big-box retailers that operate in multiple states, the 2013 legislation will require them to file their returns using the ‘combined’ filing method, which keeps them from sheltering their New Mexico profits in other states. This change is expected to increase tax revenue from the retail sector. While this is a positive change in the CIT code, the combined reporting requirement should be expanded to include all multi-state corporations. Policy-makers should also require an annual tax expenditure report that accounts for all tax credits, deductions, and exemptions, and analyzes them for effectiveness, as well as include sunsets for all future tax expenditures.

Tax cuts to lure companies to the state are a dubious form of economic development. While corporations looking to set up shop may find the state’s corporate tax code attractive, other more important factors may outweigh tax considerations.