Download this policy brief (April 2013; 4 pages; pdf)

The Senate Finance Committee substitute for HB-641—also referred to as the ‘omnibus tax bill’—was passed in the closing minutes of the 2013 legislative session on March 16. The process for passing this bill was deeply flawed, as was much of the reasoning behind its need. The way in which the bill was amended and voted upon left little time for legislators to understand it or debate its merits, no time for determining its potential fiscal impact, and no time for public input. The original HB-641, which was a set of fairly minor changes to the film tax credit, was changed significantly when the Senate Finance Committee (SFC) attached 35 pages of amendments to it. Because so little time was left in the session, the Legislative Finance Committee could not produce a fiscal impact report (FIR), so legislators had no idea how much it would cost. The little information on the fiscal impact that was given to legislators was inaccurate. The House of Representatives was told the bill would have a positive revenue impact every year, when in fact, the state will lose $100 million in fiscal years 2016 and 2017.

The stated rationale for the costliest portions of the bill was that they would make New Mexico more competitive against other Western states for new jobs. While few businesses will turn down a tax break, experts know that a state’s tax system is only a part—and not the most important part—of a company’s decision about where to set up shop. For example, a well-educated workforce is generally a more important consideration for businesses than tax rates. In short, there is no evidence that corporate tax cuts create jobs. What corporate tax cuts inevitably do is starve public services, like education and health care, that are relied upon by working families, their kids, and the community at large. New Mexicans will either have to make do with fewer services or will have to pay more in taxes to fund them.

This policy brief will explain the components added to the bill and examine the rationale for each. This brief will also look at the impact of the bill on the overall New Mexico tax structure and, finally, examine the promises made by the bill’s proponents.

Major—and Most Costly—Provisions

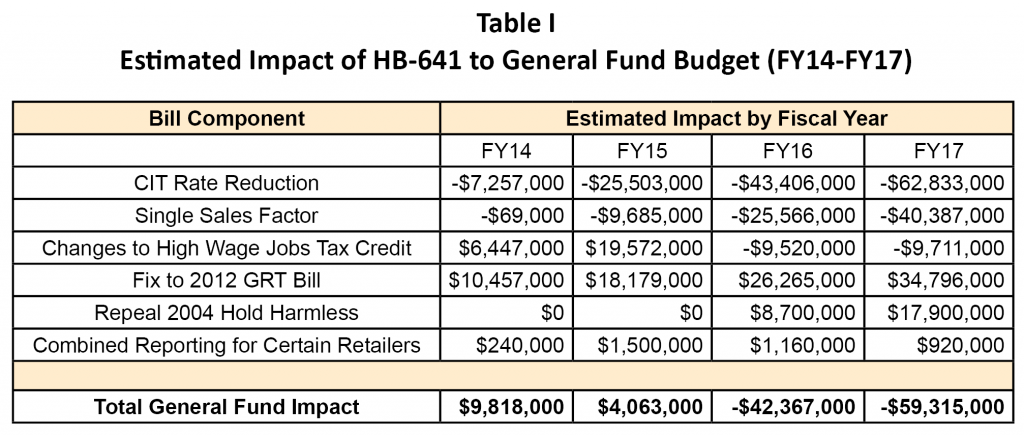

According to the Legislative Finance Committee’s fiscal impact report (FIR), which was not issued until after the session had ended, HB-641 will have a slight positive revenue impact on the state general fund for the first two fiscal years it is in effect (about $10 million in FY 14 and only $4 million in FY 15). The fiscal impact then becomes negative in FY 16 (losing $42 million) and FY 17 (losing $59 million). The FIR does not extend past FY 17, but the fiscal impact will continue to be negative.

The two major changes the bill makes to the state corporate income tax (CIT) structure will end up costing the state one-quarter of its CIT revenue. Those changes are:

- a reduction in the top CIT rate from 7.6 percent to 5.9 percent in stages between FY 13 and FY 18 for a revenue loss of $43.4 million in FY 16 and $62.8 million in FY 17; and

- the provision for single sales factor apportionment of net profits for manufacturing corporations. This will lead to a revenue loss of $25.6 million in FY 16 and $40.4 million in FY 17.

The rationale behind the CIT rate cut is that it will bring our CIT rates more in line with surrounding states, thereby prompting corporations to move here. There is no evidence that this will be the end result, it is very unlikely to produce enough new business to replace the lost revenue, and it’s a giveaway to corporations already doing business here.

The single sales factor (SSF) method for apportioning corporate taxes will allow manufacturers to allocate their taxable profits to the state where their products are sold, rather than to the state where their manufacturing facilities and payroll are located. In the case of New Mexico, very little of the products of a manufacturer like Intel are sold in the state. Meanwhile, Intel has significant property and payroll in New Mexico and benefits from the infrastructure and programs provided by the state. The shift to the single sales factor formula for manufacturers will mean that the state will provide physical and legal infrastructure and services to manufacturers here free of charge. This is a violation of the ‘benefit principle’ of public finance economics, which holds that when government provides a benefit in the form of a good or service to a private firm, that firm should contribute to the cost of that good or service. In this case, a manufacturer will be able to take advantage of New Mexico’s educational, transportation, and legal infrastructure without paying for it.

The idea behind the SSF change was that it would incentivize manufacturers to move here and encourage those already here to expand. But like the CIT rate cut, there are no guarantees. One of the original SSF bills included a trigger—manufacturers could not use the SSF for determining CIT unless they had made an investment in New Mexico. That provision did not make it into HB-641.

Fixes to Past Problems

Several provisions of HB-641 are attempts to fix mistakes in tax bills already enacted. While these are laudable and necessary fixes, they do not bring in nearly enough revenue to offset the loss from the changes to corporate income taxes. The High Wage Jobs Tax Credit, which was passed several years ago to incentivize the creation of high-wage jobs, had become a significant and continuing growing revenue loser in more recent years. The fix results in a revenue gain of $6.5 million in FY 14 and $19.6 million in FY 15. However, those increases change to revenue losses of $9.5 million in FY 16 and $9.7 million in FY 17 because HB-641 also removes a sunset provision that would have repealed the credit after FY 15.

There is also an attempt to repair the so-called gross receipts tax ‘pyramiding fix’ from the 2012 legislative session. That law attempted to solve a non-existent problem with the gross receipts tax law by allowing manufacturers to deduct services used in manufacturing a product from the gross receipts tax. It was originally expected to cost the state about $40 million annually, but in actuality was approaching a cost of $91 million. The fixes to the anti-pyramiding statute would bring in $26.3 million in FY 16 and $34.8 million in FY 17. Since the fiscal impact of the original bill was so badly underestimated, this should be taken as a very soft estimate, with a significant risk of being wrong again.

Lastly, we’ll look at the ‘hold harmless’ fix. In 2004, the Legislature made food and most medical care deductible under the gross receipts tax. At the time, local governments were unhappy about this prospect because it would result in the loss of revenue on the city and county levels. To address these concerns, the Legislature attempted to ‘hold local governments harmless’ from the elimination of a large part of their tax base by replacing it with state revenue. This ‘hold harmless’ provision ended up being very expensive for the state general fund, costing an estimated $140 million in FY 14.

HB-641 remedies this revenue loss by repealing the hold-harmless distribution to local governments. The phase-out would take effect in increments of 6 percentage points each year over 15 years. In FY 16 this will yield $8.7 million and $17.9 million in FY 17. In years further out the revenue gain for the general fund would increase by 6.6 percentage points each year.

Recognizing that this could devastate municipal budgets, the bill amenders allow local governments to raise their gross receipts tax rates by up to three-eighths of a percent. This is a revenue gain for the state general fund at the cost of a revenue loss for the local governments. Those local governments that make up the loss by raising their gross receipts tax rate will be passing the loss along to consumers—meaning this tax will hit those with the lowest incomes the hardest.

A Toothless Provision for Progressivity

Legislators have worked for several years to pass unitary combined reporting legislation as a matter of tax equity. HB-641 contains a very watered-down version to mollify those legislators. Combined reporting requires multi-state corporations to combine their profits in all states before determining how much CIT is due to each state. In general, this is a more accurate way of apportioning profits under the corporate income tax. Requiring combined reporting disallows some of the more common tax avoidance strategies of retailers, banks, restaurant chains, and other multi-state corporations.

Unfortunately, as written into HB-641, combined reporting is all but toothless. It is restricted to specific kinds of retail corporations, and corporations that have a non-retail facility (a distribution center, for example) in New Mexico that employs more than 750 workers are exempted. Wal-Mart and Lowes home improvement stores may be carved out of the requirement to use combined reporting because they have warehouses or customer service centers in New Mexico. The combined reporting segment of HB-641 has a ridiculously slight positive impact of $240,000 in FY 14 and $1.5 million in FY 15. Revenue is predicted to decline in the out years to less than $1 million as, according the to FIR, “corporations restructure operations to minimize their tax liability.”

Conclusion

The reduction in the corporate tax rate, enactment of the single sales factor formula, and repeal of the 2004 hold-harmless provision will have the effect of shifting overall tax responsibility from corporations to consumers. This will increase the regressivity of the state’s tax system, because corporate income taxes are paid by the owners of corporations—the shareholders. Shareholders are likely to be high-income individuals who live out of state. The gross receipts tax affects low-income individuals disproportionately because they must spend a higher portion of their income on goods that are taxed.

This conclusion is verified in analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. ITEP’s analysis found that HB-641 will result in a tax cut for higher-income taxpayers and a tax increase for lower-income taxpayers. The two cuts in the corporate income tax will result in a tax cut of $704 for a family making $400,000 or more. The CIT cuts will not help low-income families at all. Again, any increase in gross receipts taxes will have the greatest impact on the lowest-income taxpayer.

Furthermore, the promise that HB 641 will result in increased economic activity and employment is utterly empty. The same promise was made to New Mexicans when top personal income tax rates were reduced in 2003. A recent study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities1 confirmed what close observers of the New Mexico economy had long thought: the economic activity and growth of the period from 2003 to 2008 was powered by high oil and natural gas prices, not by the 2003 personal income tax cuts. That growth was augmented by the impacts of the national housing bubble on New Mexico construction employment. If the effects of oil and natural gas prices and the housing bubble are subtracted, New Mexico economic growth was sub-par in the 2003-2008 period. The argument that HB-641 will result in accelerated economic activity is equally far-fetched: the personal income tax cuts of 2003 were a very expensive public policy experiment and the result was no measurable increase in economic activity. This experiment will end with the same result.

Endnotes

1 State Personal Income Tax Cuts: A Poor Strategy for Economic Growth, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Washington, DC, March 21, 2013

Many thanks to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy for their analysis of the impact of HB-641 by family income group.