Introduction

Download this report (Aug. 2013; 16 pages; pdf)

by Gerard Bradley, MA

It’s long been understood that one of the most effective ways to lift people out of poverty is to improve their levels of educational attainment. High school graduates earn more than those who do not graduate. Those who attend college earn more still, even if they do not complete a degree program. College graduates earn the highest incomes. The higher one’s educational attainment, the lower their rates of unemployment, and the more likely their children will do well in school and go on to college themselves. In addition, as the nation’s manufacturing sector continues to shrink, more and more jobs require a college degree.

But a college education is expensive and New Mexico has one of the highest poverty rates in the nation. Student loans are plentiful, but the ever-growing levels of burden on young adults from student debt are becoming a significant national problem. College affordability is an issue New Mexico’s state lawmakers addressed with some success in 1996 with the creation of the New Mexico Legislative Lottery Scholarship. The scholarship is paid for by the sale of lottery tickets and is administered through the Lottery Scholarship Trust Fund.

The scholarship covers tuition at New Mexico universities for students who graduate from a New Mexico high school, begin college the following semester, and maintain a grade point average of 2.5. The lottery scholarship is available to students meeting these criteria even if their parents can afford to send them to college without financial assistance.

For nearly 20 years, the lottery scholarship has made college attendance possible for many New Mexicans who would have otherwise been unable to attend. Many of them are, undoubtedly, the first in their families to do so. However, the solvency of the trust fund is in jeopardy.

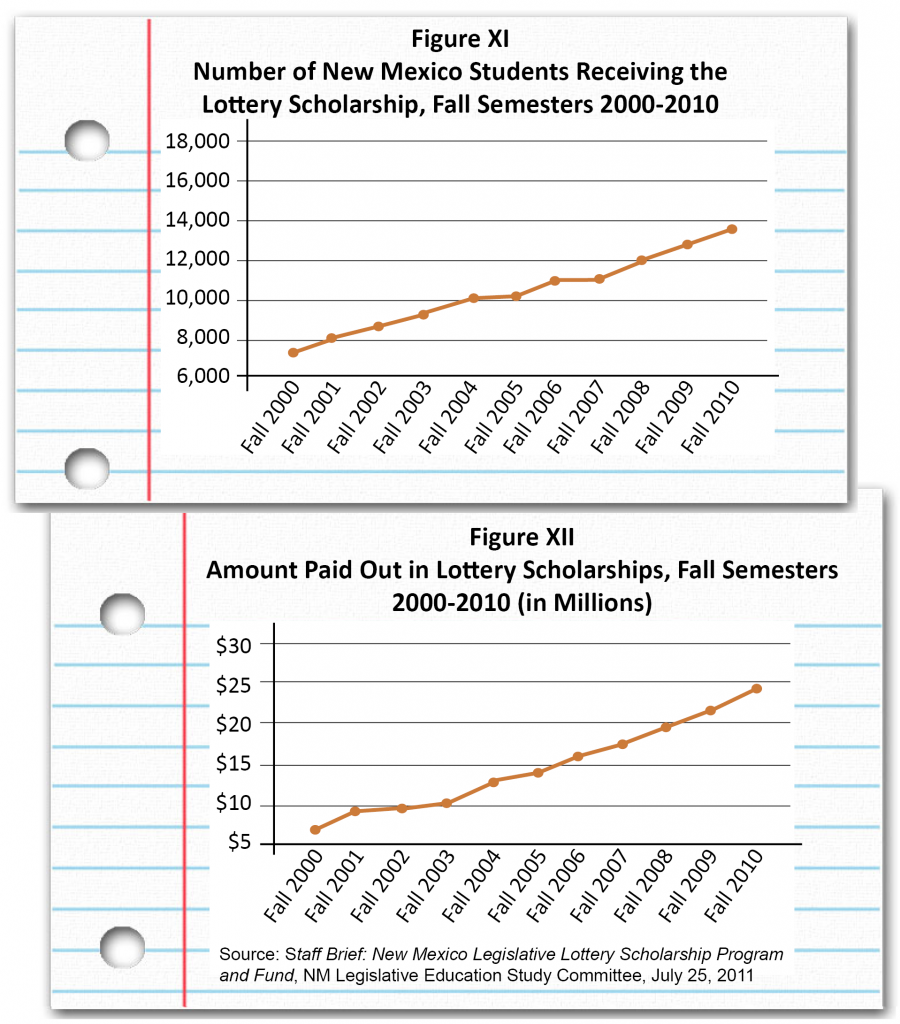

The number of students receiving the lottery scholarship has grown tremendously, nearly doubling from 7,377 students in the fall semester of 2000 to 13,619 students in the fall semester of 2010. In the meantime, lottery ticket sales have leveled off, meaning revenue into the scholarship trust fund has not kept up with increased demand.

When the Great Recession led to revenue shortfalls for the state, lawmakers responded by cutting funding for higher education. New Mexico’s colleges and universities had few choices beyond raising tuition. Increases in tuition and student demand, along with flat ticket sales, have had the effect of rapidly depleting the scholarship trust fund. The state Legislature approved a one-time infusion of money into the fund in early 2013. With no additional tuition increases, this short-term fix will keep the fund from depletion until the end of fiscal year 2014 (FY14). Beyond that, some changes in award amounts or eligibility levels must be made or the trust fund will run completely dry.

The best solution for the lottery scholarship is to base it on student financial need. This would allow the trust fund to be restored and keep it available for New Mexico families trying to escape poverty.

Other policies could make college even more affordable for the state’s lowest-income students. Need-based aid, such as the College Affordability Grant should receive more revenue. New Mexico could also consider recent policy proposals from other states, such as waiving tuition for youth who have aged out of the foster care system, and creating a “Pay it Forward” program that could take the place of costly student loans.

Anatomy of Student Aid

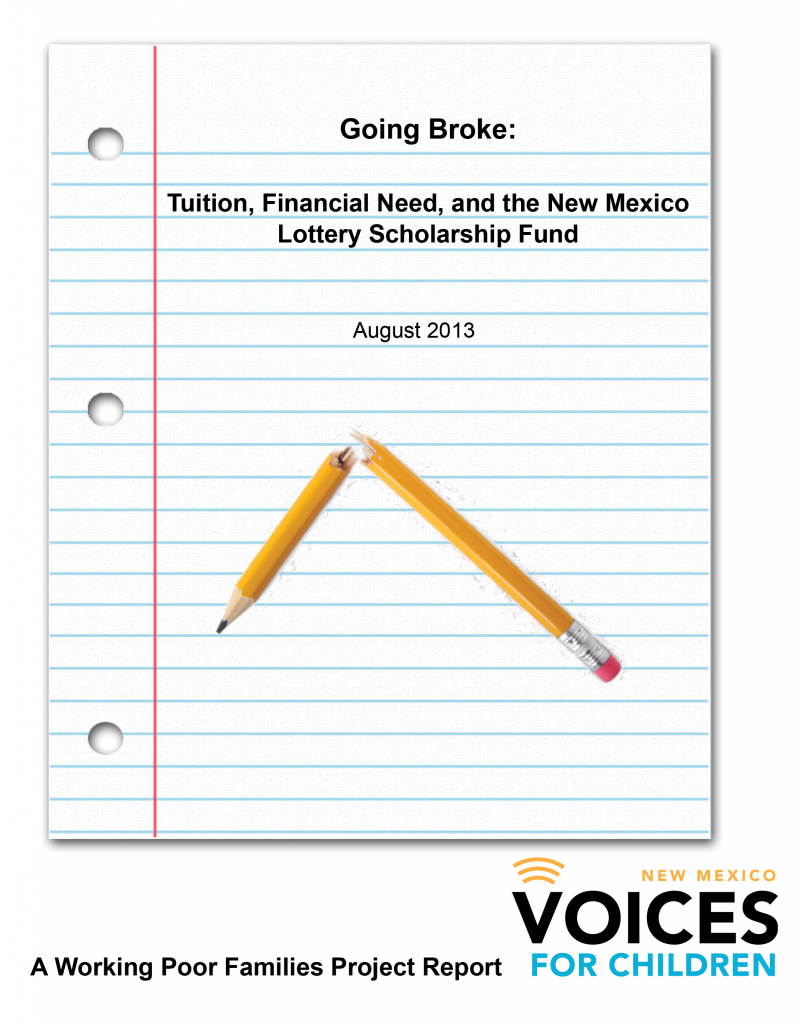

In 2012, the bulk of student financial aid in New Mexico—48 percent—was from loans, as shown in Figure I. The next largest share—28 percent—came from federal Pell Grants. Just 8 percent came from the lottery scholarship. The rest—16 percent—came from other scholarship and aid programs, and student support from individual schools.

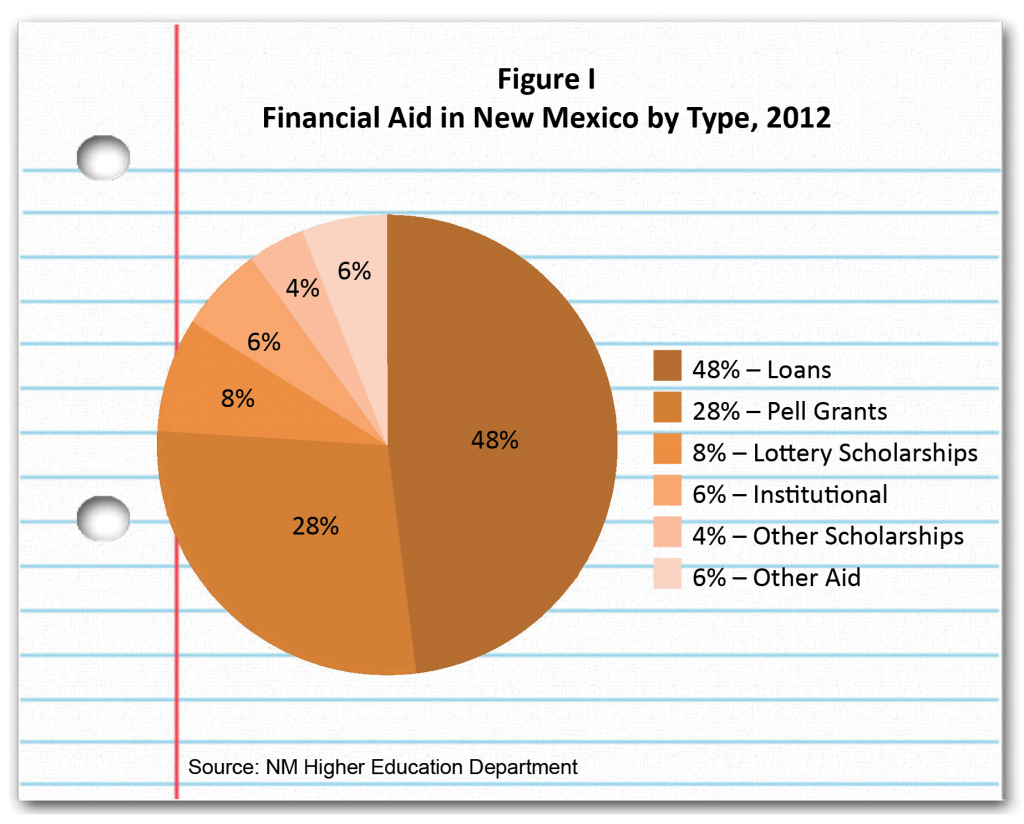

States can allocate student financial aid for higher education on the basis of financial need or on academic merit. As a poor state, New Mexico has a large share of families who need financial aid in order to put their children through college. Even so, the state bases most of its student aid distribution on academic merit rather than on student financial need. As shown in Figure II, just 29 percent of the state’s student financial aid is based on financial need criteria, while 71 percent is based on academic merit.

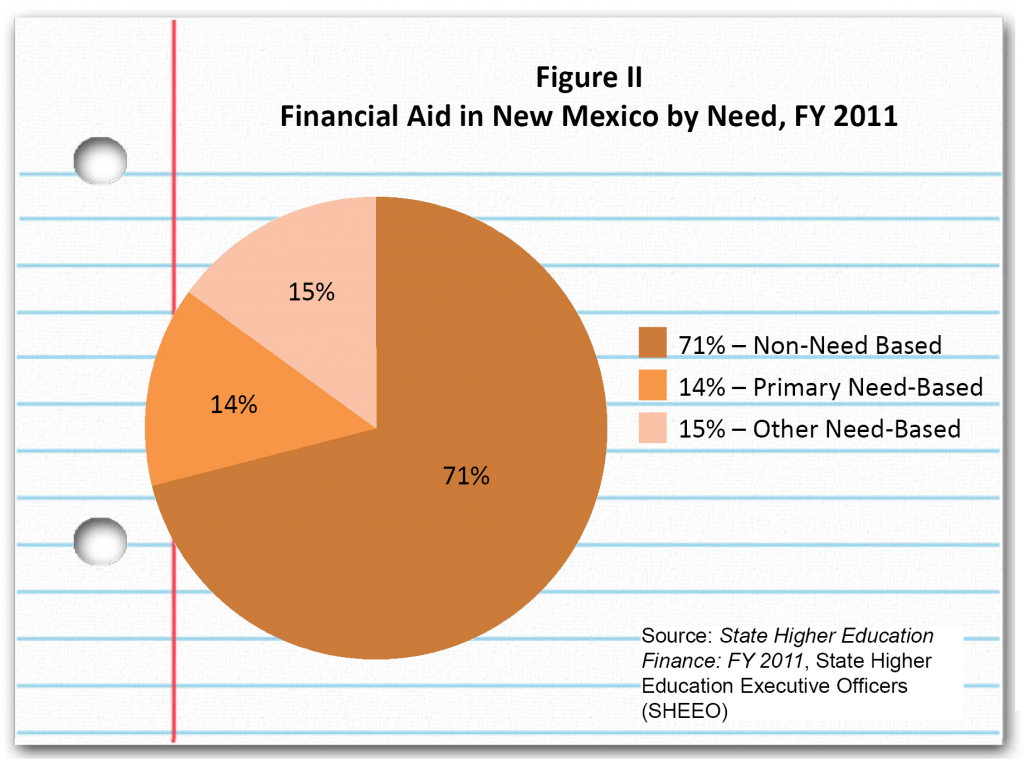

New Mexico’s distribution is exactly the opposite of the national average for need-based criteria—71 percent—as shown in Figure III. Only eight other states rely more heavily on merit-based financial aid than New Mexico, while 18 states base virtually all—between 99 and 100 percent—of their college aid on financial need.

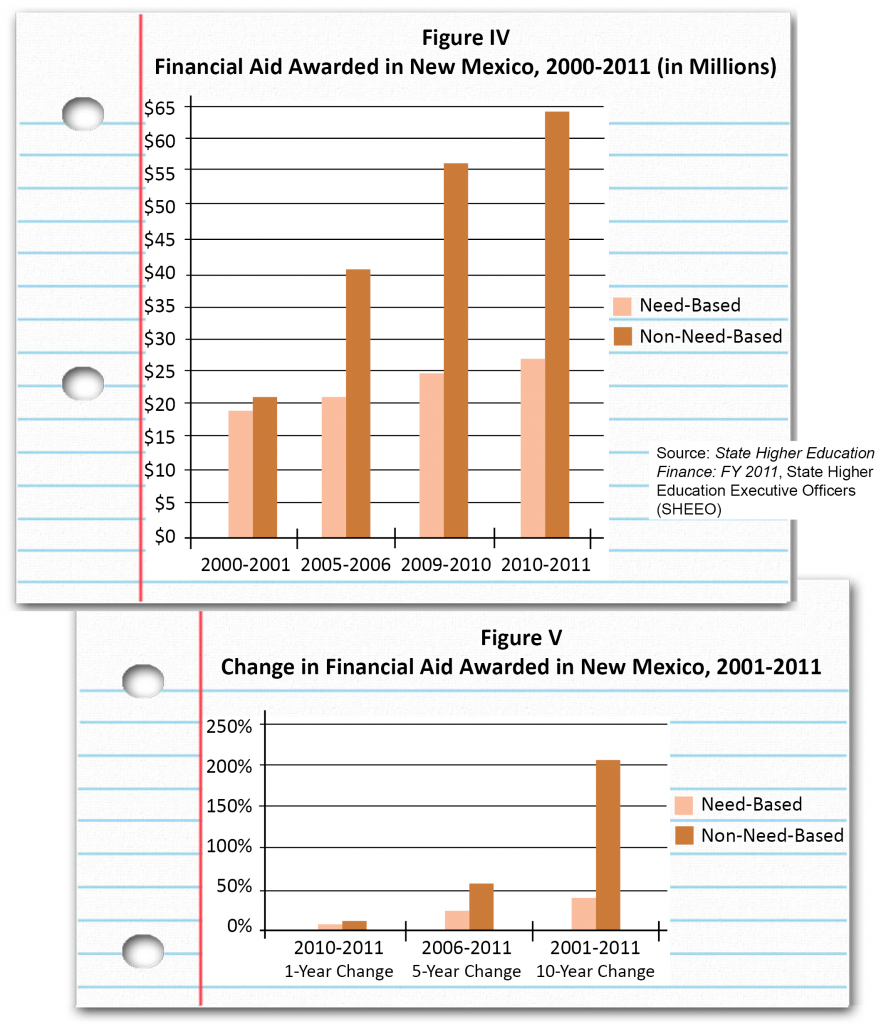

New Mexico’s spending on need-based aid was not always so much lower than spending on merit-based aid. Over the last decade, New Mexico spending on merit-based grants far outpaced that for need-based grants, as shown in Figures IV and V.

Higher Education Funding

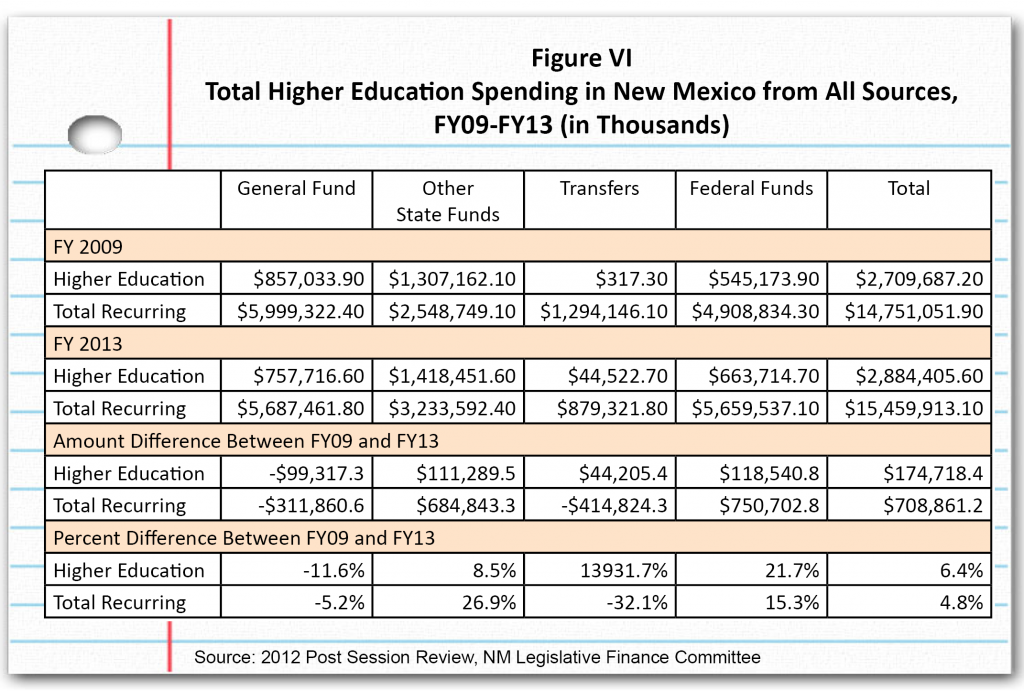

Higher education in New Mexico receives funding from several sources, such as the state’s general fund, the federal government, and royalties from oil and natural gas extraction. Total state general fund spending peaked in FY09 at $6 billion, a year after the onset of the recession in late 2007. As the Great Recession began taking its toll on the state budget, general fund expenditures for higher education were put on the chopping block. Between FY09 and FY13, state general fund spending for higher education fell by almost $100 million, or 11.6 percent. General fund expenditures for all spending categories fell by $311 million, or 5.2 percent, during that time period—meaning almost one-third of all general fund budget cuts were to higher education.

As Figure VI shows, while state spending fell by 11.6 percent, federal funding increased by 21.7 percent—meaning total higher education expenditures from all revenue sources rose by 6.4 percent between FY09 and FY13. Still this increase was not enough to cover inflation and population growth and forestall tuition increases.

At the same time, money in the College Affordability Fund, which provides needs-based assistance, was swept up to cover shortfalls in revenue. It has not been replenished.

Deep Spending Cuts

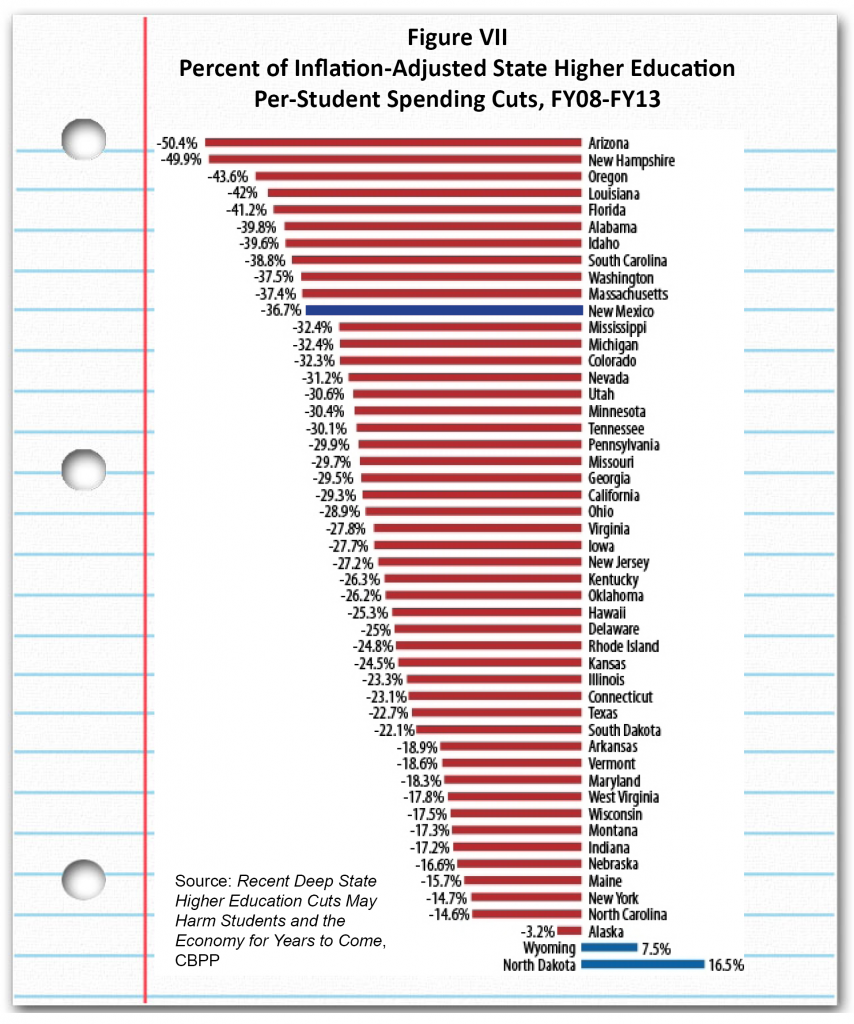

A valuable perspective on funding for higher education comes from looking at state spending per student adjusted for inflation. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) recently released a report1 that does just that. The CBPP report compares inflation-adjusted, per student state expenditures on higher education over the course of the recent economic downturn both by percent and amount. The CBPP report found that in New Mexico, state higher education spending per student fell by 36.7 percent between FY08 and FY13 after adjusting for inflation (Figure VII).

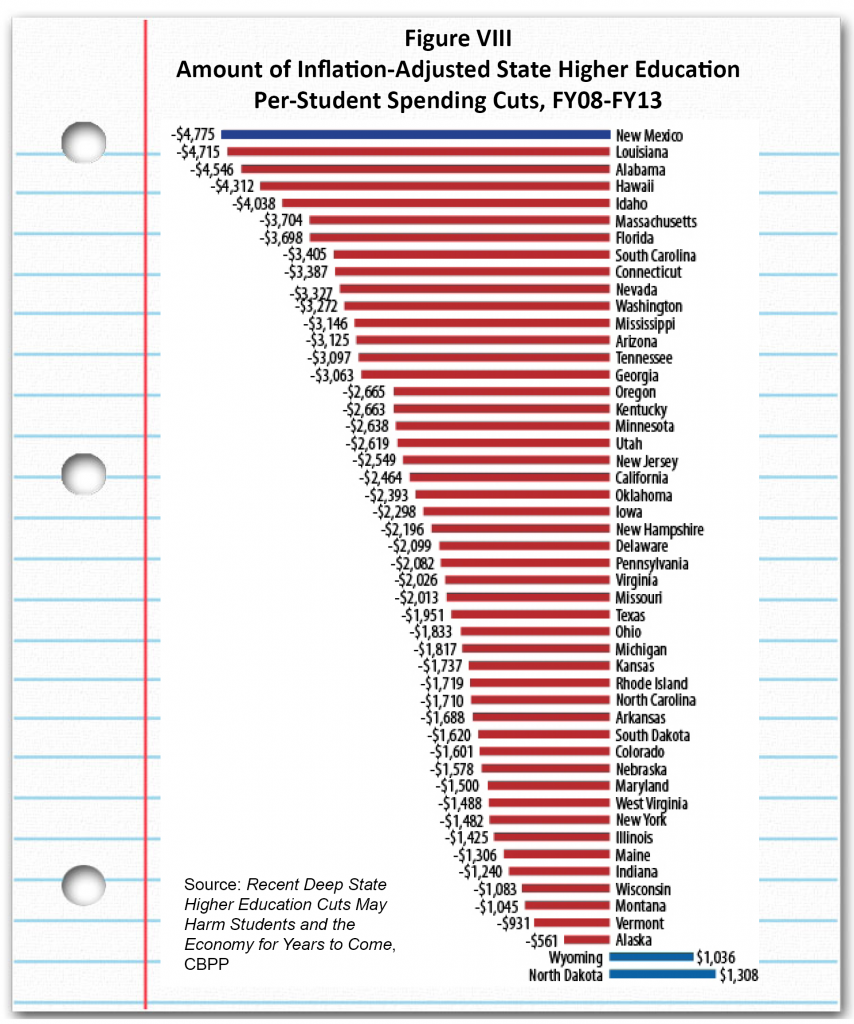

The CBPP calculated that the inflation-adjusted reduction in spending per student in New Mexico was the highest amount among all of the states at $4,775 over that time period (Figure VIII). At the same time as state spending per student has decreased, tuition spending in New Mexico has gone up by 21.7 percent or $1,015 on an inflation-adjusted basis. New Mexico tuition increased by much less than the drop in state support per student because of assistance from the federal government over that time period.

Tuition and Enrollment Increases

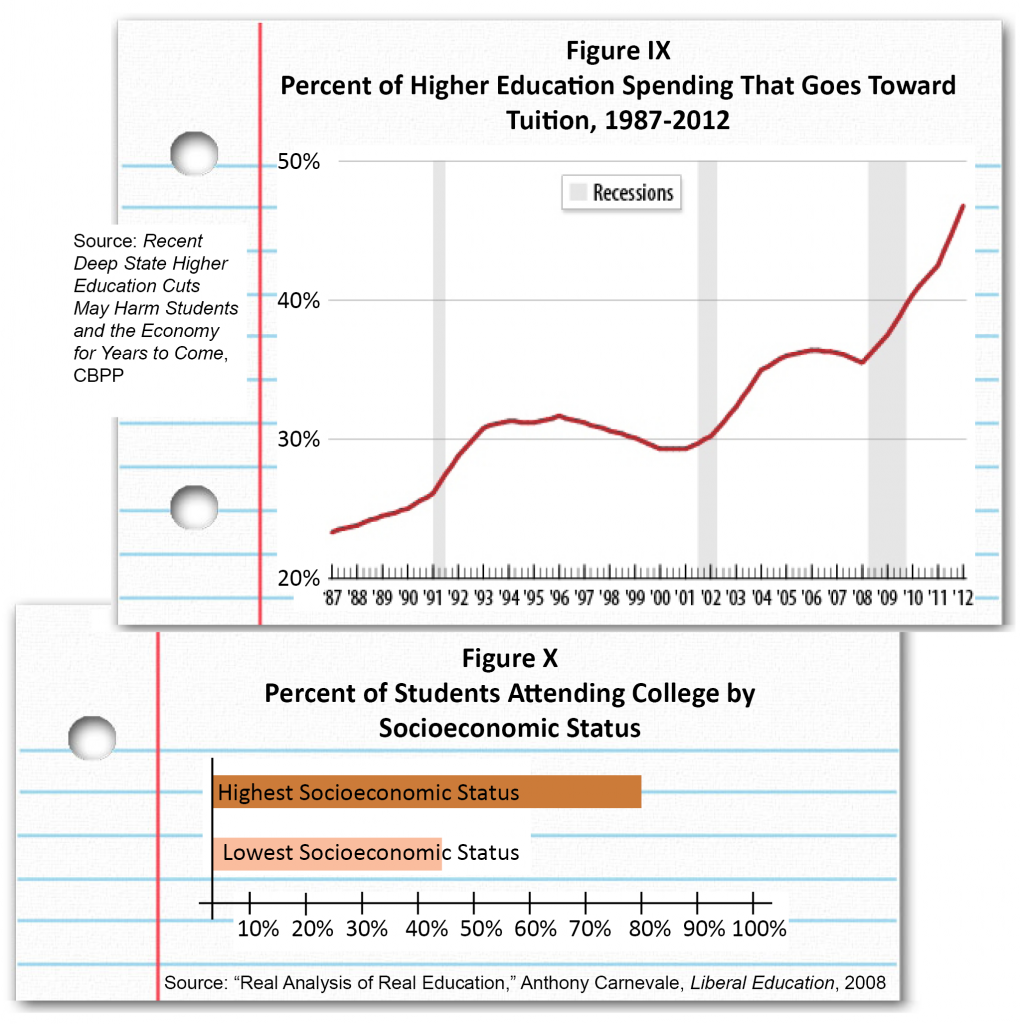

New Mexico’s increase in tuition is part of a national trend. Tuition now makes up 50 percent of the total money spent on higher education nationwide (Figure IX). That has grown from about 36 percent prior to the recession. Rising tuition puts additional pressure on students from lower-income groups wishing to attend college. Anthony Carnevale, in a much-cited article2 in the journal Liberal Education, reported that 80 percent of students in the highest socioeconomic status group attended college while only 40 percent of students from the lowest socioeconomic group attended college (Figure X). Since Carnevale’s research was done before the onset of the Great Recession, the economic pressure on lower-income families can only have intensified since then. Equality of opportunity is eroded if twice as many children from higher-income families are going to college as children of lower-income families. It is not reasonable to think that academic talent is twice as concentrated in the higher-income group as in the lower-income group—the constraint on attending college is clearly economic circumstances.

Lottery Scholarship Fund: Headed Toward Insolvency

There has been a consistent increase in both the number of students receiving the New Mexico lottery scholarship and the amount awarded under the scholarship. The trends are shown in Figures XI and XII.

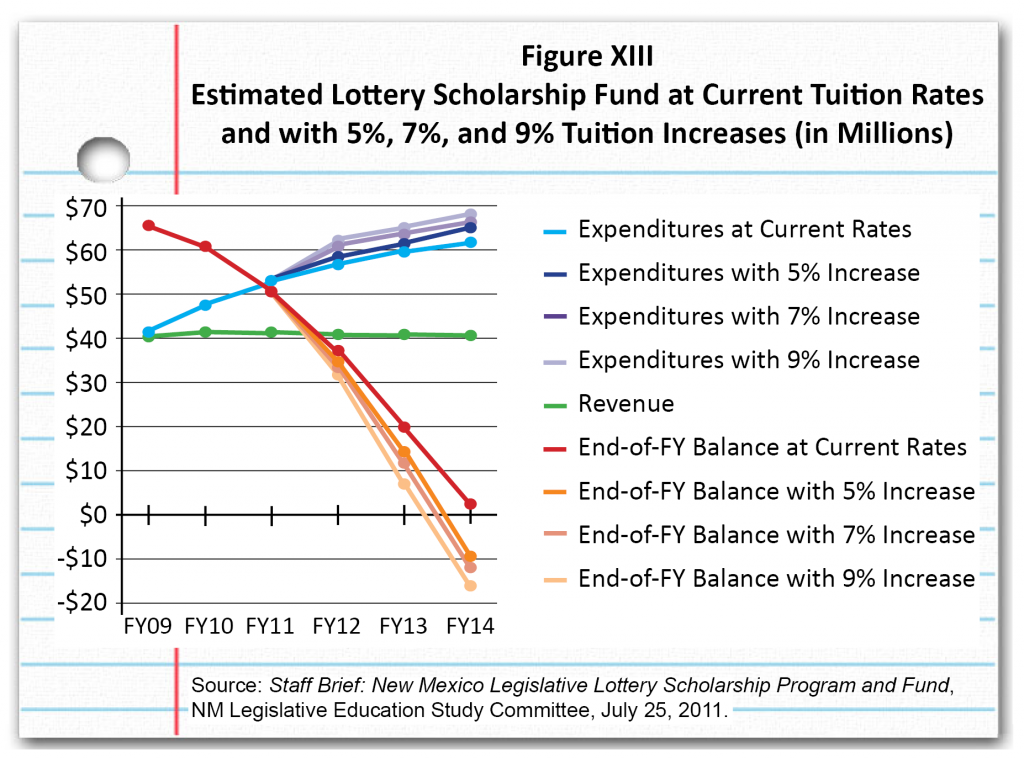

In 2011, the Legislative Education Study Committee (LESC) issued a staff brief on the solvency of the Legislative Lottery Scholarship Fund under a range of scenarios for tuition increases at New Mexico’s colleges and universities. The issue was under scrutiny because of an emerging gap between the supply of lottery scholarship dollars and the demand for the scholarship from New Mexico students. By cutting one source of state funding for New Mexico universities and colleges (the general fund) the Legislature had significantly drained another source of state funding—its own lottery scholarship.

The red line in Figure XIII represents the LESC’s simulation for the end-of-fiscal year balance of the lottery fund if no changes are made to tuition rates. Even with no tuition increases, the fund begins to fall significantly in FY10 and is on the verge of depletion by the end of FY14, with a balance of just over $300,000.

The orange lines in Figure XIII represent the LESC’s simulation for the end-of-fiscal year balance of the lottery fund under tuition increases of 5, 7, and 9 percent beginning in FY12. This model shows that, by the end of FY14, the fund would have a $9.4 million deficit with a tuition increase of 5 percent; a $13 million deficit with a tuition increase of 7 percent; and a $16.6 million deficit with a tuition increase of 9 percent.

The LESC report also notes that undergraduate resident tuition increased by 6.9 percent at the NM Institute of Mining and Technology, 7.9 percent at NM State University, and by 6.8 percent at the University of New Mexico. Statewide, the undergraduate tuition increased 10 percent between FY11 and FY12.

These constraints on lottery scholarship funding were not unexpected. A year prior to the LESC staff brief on the solvency of the trust fund, the staff had issued a memorandum making several recommendations regarding tightening eligibility requirements for the lottery scholarship.

The recommendations were to increase the merit-based requirements and establish a scholarship-for-service program using the existing model for students in the health care field for qualifying for the lottery scholarship.

Policy Recommendations

Beyond protecting the viability of the lottery scholarship, New Mexico should do more to address the rising cost of college and the growing burden of student debt. Given New Mexico’s high rate of poverty, the right course of action is to make college more affordable for low-income students. This can be done in a number of ways:

- Make the lottery scholarship need-based. There could be a complete shift to need-based criteria or a blending of merit-based criteria with need-based criteria. This would slow the depletion of the lottery scholarship fund without leaving low-income students behind.

- Restore the College Affordability Fund to pre-recession levels. Prior to the recession, the College Affordability Fund had a balance of nearly $100 million. But lawmakers raided the fund during the recession to make up for revenue shortfalls. In 2013, the state began to see “new” revenue—that is, revenue beyond what was needed for a flat budget. Much of it was given away in tax breaks for profitable corporations, even though such a “job creation” tool is dubious at best. At least a portion of any new revenue in 2014 should be invested to restore this important fund.

- Waive tuition for young adults aging out of the foster care system. New Mexico could also adopt a measure recently signed into law by Arizona Governor Jan Brewer. The law (SB-1208) waives tuition for foster children at Arizona universities. The students must have been in the state foster system while under the age of 17, must be legal residents, and maintain good academic standing. Young adults aging out of the foster care system generally have few, if any, social or economic supports to help them pursue a college education. Because such a waiver would serve a relatively small number of New Mexicans, the cost would be fairly low.

- Enact a Pay Forward, Pay Back pilot program. New Mexico could also consider legislation similar to the “Pay Forward, Pay Back” bill currently being debated in the Oregon Legislative Assembly. If passed, the bill (HB-3472) would create a pilot program that would waive tuition and fees at Oregon universities for eligible students willing to sign a binding contract to pay back a small percentage of their income after graduation for a specified number of years. Such a program could differ from standard student loans in a number of critical ways: The student would not be negatively impacted by rising tuition costs (or changing interest rates); the payback amount would be based on the level of their post-graduate income rather than on the amount borrowed; and the amount paid over time would not increase due to interest charges.

Appendix

Lottery Scholarship Legislation Introduced in the 2013 Legislative Session

Eight bills and memorials regarding the lottery scholarship were introduced during the 2013 legislative session. Only two passed. The six that relate most to the issues addressed in this report are described here. The other two bills expanded scholarship eligibility to various groups, such as students who wish to take a year or two off after high school before attending college, and students who had completed a graduate equivalency diploma (GED). These bills did not address the issue of trust fund solvency and, therefore, would have made the problem worse. Only one memorial requested a study on restoring the solvency of the trust fund and it failed.

- House Memorial 101 requested that the Higher Education Department (HED) form a work group to study the solvency of the lottery scholarship fund in cooperation with the Legislative Education Study Committee (LESC) and the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC). HM-101 requested that the work group compile student data and study four basic ways of restoring the solvency of the lottery scholarship program by:

1. increasing the merit qualifications for receiving the scholarship;

2. instituting financial need qualifications for receiving the scholarship;

3. providing additional funding for the scholarship beyond what is provided by the New Mexico Lottery; and

4. reducing the amount received by lottery scholarship recipients.

HM-101 also asks the HED to study allowing one or more gap years between high school completion and enrolling in college. HM-101 did not pass.

- House Memorial 94a requested that the LESC study the circumstances in which Native American tribal colleges are excluded from state higher education programs, policies, procedures, and accompanying budget and funding processes, including the lottery scholarship. The memorial requests that the LESC draft a report with findings and recommendations to address how tribal colleges shall be included in state programs, policies, procedures, and accompanying budget and funding processes. One of the intents behind HM-94a is to permit tribal colleges to participate in the lottery scholarship program. HM-94a passed.

- Committee Substitute for House Bill 309 attempted to address the problem of solvency by reducing the scholarship amount and restricting eligibility. CS/HB-309 would have reduced the number of semesters that a student could receive the scholarship from eight to seven. CS/HB-309 would have also subtracted the value of any need-based aid that a student received from the lottery scholarship award amount. In addition, CS/HB-309 specified a flat amount of tuition aid that would be provided by the scholarship. This amount would not change as tuition was raised, meaning students would have to come up with the shortfall. This bill also specified that there would always be a balance of $10 million in the scholarship trust fund. CS/HB-309 adopted the second and fourth alternatives from the HM-101 list of methods for re-establishing the solvency of the trust fund, but did not pass.

- House Bill 586 would have changed the eligibility qualifications for the lottery scholarship by increasing the academic requirement to a high school GPA of 2.7 for four-year universities and 2.5 for two-year colleges. In addition, HB-586 would have set up a simple tiered set of means testing for scholarship eligibility: students with a family income of $100,000 or more would receive 70 percent of the full lottery scholarship; students with a family income of $99,000 to $54,000 would receive 85 percent of the full lottery scholarship; and students with a family income of less than $54,000 would receive the full lottery scholarship. This combination of increasing the merit-based qualification with needs testing would have reduced expenditures from the lottery scholarship trust fund, which would have contributed to the solvency of the fund. It did not pass.

- Senate Bill 451 focused on raising the eligibility conditions for receiving and retaining the lottery scholarship. In order to qualify for the scholarship a student would have needed a score of 21 on the ACT or 1550 on the SAT. In order to retain the scholarship the student would have to post a 2.75 GPA each semester. Students attending a four-year institution would need to be enrolled in 12 hours of non-remedial course work. SB-451 also contained a punitive provision that would have discouraged students from applying for the lottery scholarship in the first place: the scholarship would be have to be paid back if the student did not meet the qualifications each semester and graduate. SB-451 seemed designed to make the conditions for receiving the lottery scholarship so onerous and risky that many fewer students would apply. SB-451, which represented the least palatable of all the alternatives proposed during the 2013 session, did not pass.

- Committee Substitute for Senate Bill 113 and Committee Substitute for Senate Bill 392 were the solution to the solvency problems of the lottery scholarship fund that were adopted during the 2013 legislative session. These bills require that 25 percent of the total amount of money distributed to the Tobacco Settlement Permanent Fund be rerouted to the lottery scholarship fund in FY14. This is expected to be $9.875 million. Although this amount does not completely cover the expected difference between the receipts and disbursements of the lottery scholarship fund for FY14, it solves the majority of the problem. However, as this is a one-time distribution, the problem will rise again in FY15 and future years. CS/SB-113 and CS/SB-392 were passed by the Legislature and signed by the Governor and became Chapter 228 of the laws of 2013.

Endnotes

1 “Recent Deep State Higher Education Cuts May Harm Students and the Economy for Years to Come,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Washington, DC, 2013

2 “Real Analysis of Real Education,” by Anthony Carnevale, Liberal Education, Volume 94, Number 4, 2008