Teenagers and Young Adults in the State’s Workforce

Download this report (Sept. 2014; 20 pages; pdf)

Link to the press release

by Gerard Bradley, MA

In the past two decades a momentous shift has taken place within our workforce. New Mexico’s labor force, which in 1990 was dominated by workers in their prime working age (those aged 25 to 54), now has a much more significant role for workers over age 55. This is to be expected as our population ages. At the same time, the share of younger workers in the workforce has fallen. Although some of that is undoubtedly due to the Great Recession, the share of younger workers in the workforce did not rise during the economic expansion of the early 2000s. What’s more, it is common for youth under age 25 to enroll in college in higher rates when the demand for young labor is low, but that was not the case during the recession.

Inclusion in the workforce is an important rite of passage for young people: finding a job carries with it the possibility of living independently and starting a family. Failure to join the labor force can cause significant stress, both to the young workers themselves and to their parents. This report will discuss the labor force performance of teenagers and young workers both over time, and will compare conditions in New Mexico to other states in the mountain west region.

Our Changing Workforce

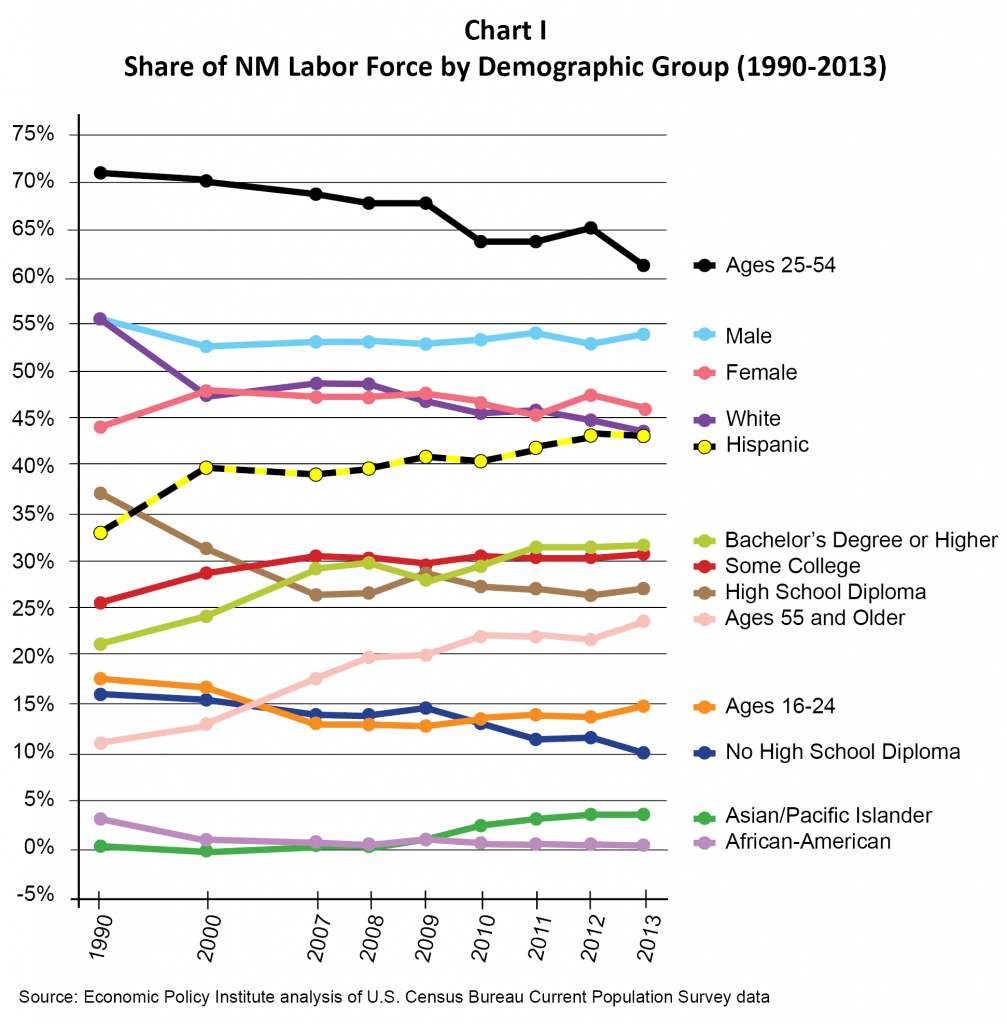

The ‘labor force’ is composed of people who are working and those looking for work (see the ‘definitions’ box). Chart I, which is compiled from a data set provided by the Economic Policy Institute, shows that the share of teenagers and young adults (indicated by the orange line) in the New Mexico labor force has been gradually dwindling over the past two decades. In 1990 people aged 16 to 24 accounted for 17.3 percent of the labor force. That share had fallen only slightly, to 16.7 percent in 2000, but continued to drop even during the economic expansion of the mid-2000s. By the onset of the Great Recession in 2007, young adults made up only 13.8 percent of the labor force. By 2013, the share of young workers in the labor force had increased slightly, to 14.5 percent, as the recovery began to take hold. It is too early to see if that slight increase represents a trend.

During the same time frame, there was also a sharp drop in the share of workers in the prime working ages of 25 to 54 (from 72 percent in 1990 to 62 percent in 2013; black line) and the drastic increase in the share of those 55 and older in the labor force (from 11 percent in 1990 to 23.6 percent in 2013; light pink line).

The educational composition of the New Mexico work force has also changed. The share of workers with less than a high school diploma (dark blue line) or only a high school diploma (brown line) has dropped, while the share of workers with some college (red line) or a college degree (lime green line) has risen. The share of workers with a Bachelor’s degree or higher varies by ethnicity: 38 percent of non-Hispanic whites, 14.2 percent of Hispanics, and 10.7 percent of Native Americans over the age of 25 have college degrees.

In terms of ethnicity, the share of non-Hispanic whites (purple line) in the workforce has fallen, from 55.6 percent to 44 percent, while the share of Hispanics (yellow and black line) has risen from 33 percent to 44 percent. In summary, the New Mexico labor force has become older, more Hispanic, and more educated since 1990.

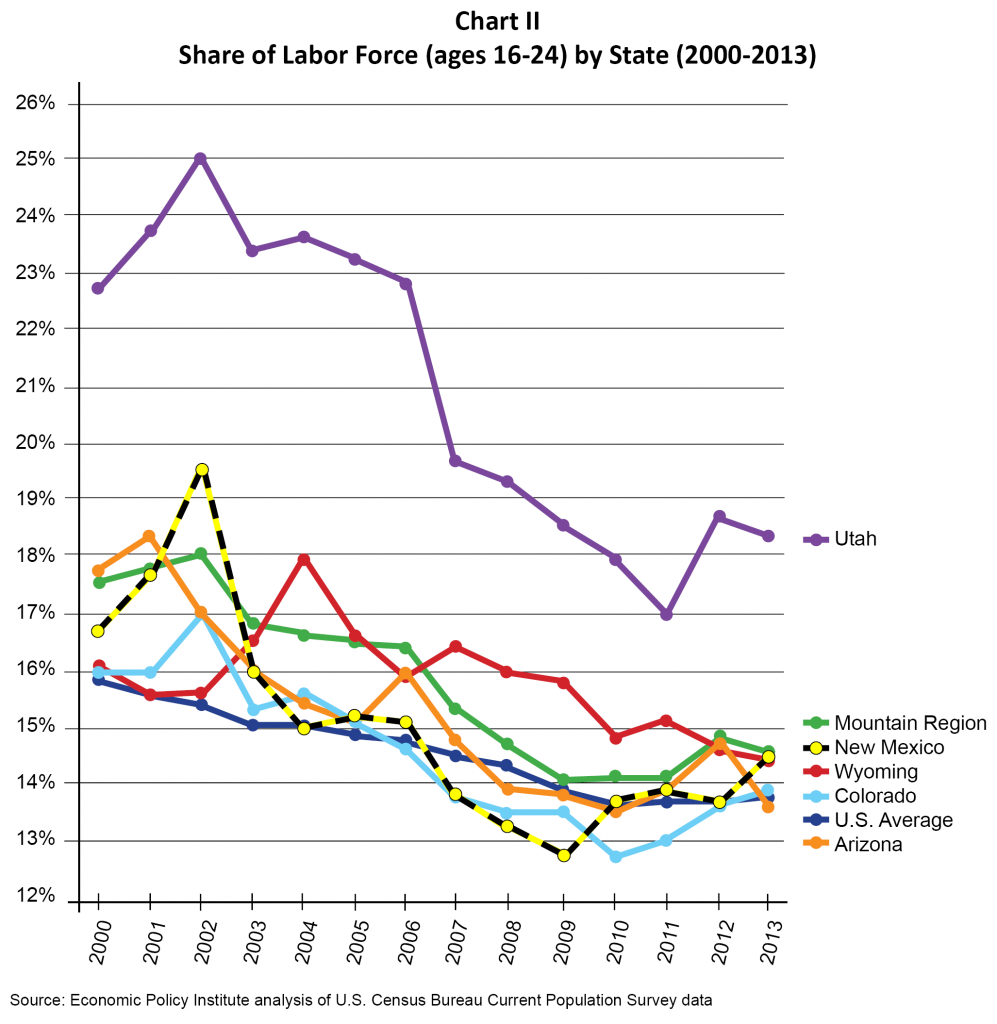

Young workers currently make up 14.6 percent of the labor force in the states of the mountain region. New Mexico’s share of young workers is very close to that average, at 14.5 percent. Chart II shows that the trend over time has been for young workers to make up a smaller and smaller share of the labor force. Since 2000, the share of young workers in New Mexico’s work force (indicated by the yellow and black line) has fallen by more than 2 percentage points, from 16.7 to 14.5 percent. The share of young workers in the labor force has fallen by 2 percentage points nationally and in the mountain division. Even in Utah (purple line), which has an atypically high share of young workers, the share has fallen from 22.7 percent in 2000 to 18.3 percent in 2013, a drop of 4.4 percentage points.

The Unemployment Rate

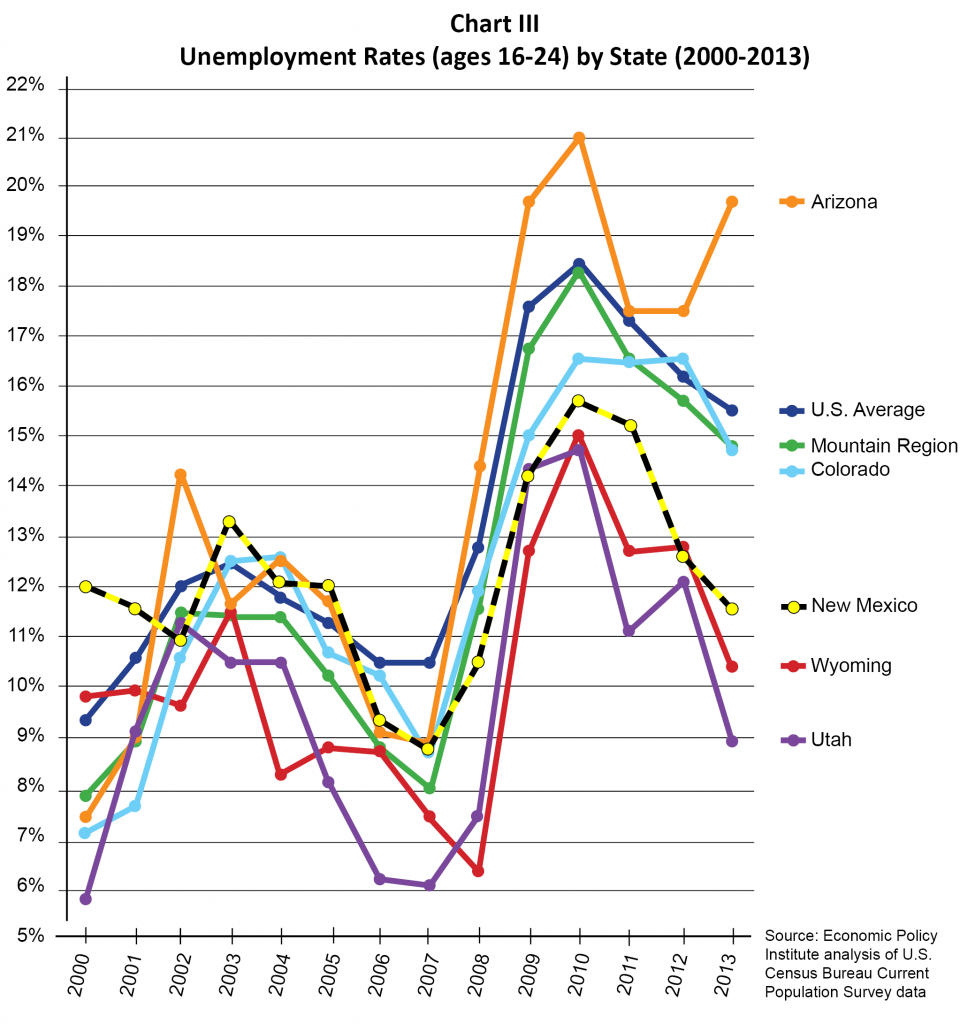

The labor force indicator that people are most familiar with is the unemployment rate, which measures the percentage of people looking for work as a share of the total labor force (which includes those who are looking for work as well as those who are working). Chart III, which presents the history of the unemployment rate over the last business cycle, shows the gradual rise in the unemployment rate for young workers in New Mexico from a low of 8.8 percent in 2007 to a peak of 15.7 percent in 2010, with a slight fall thereafter. Nationally, the 15.5 percent unemployment rate for young workers in 2013 was more than half again as high as at its starting point of 9.3 percent in 2000 (indicated by the dark blue line). New Mexico’s unemployment rate for young workers was about the same in 2013 as it was in 2000.

Labor Force Participation Rates

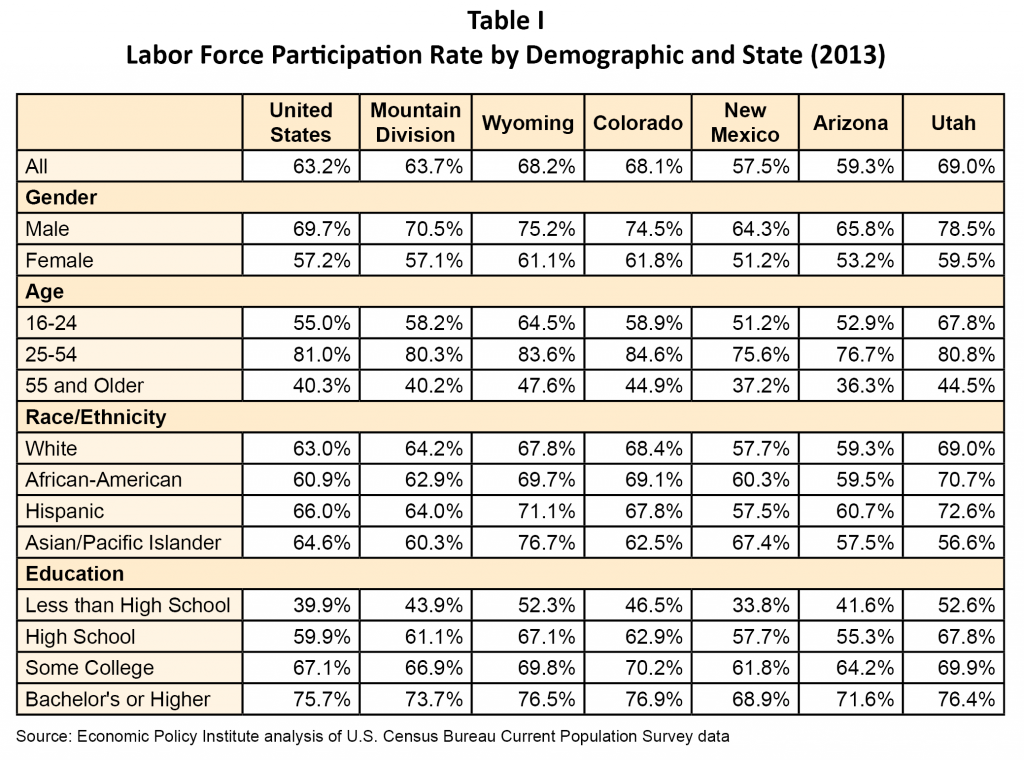

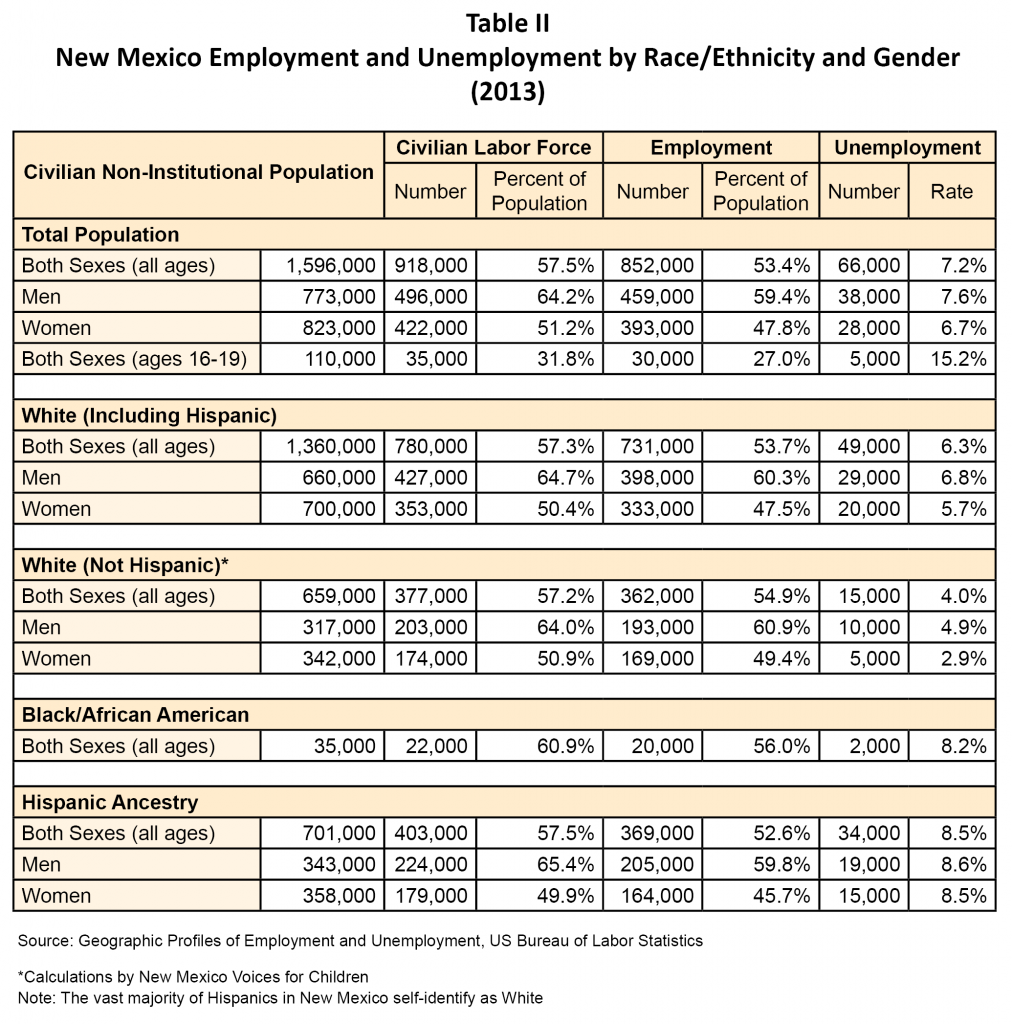

The labor force participation rate (the labor force divided by the population over age 16) is an index of employers’ demand for labor. Low labor force participation rates show that the demand for labor is weak. Table I provides a comparison of labor force participation rates for New Mexico and other states in the mountain division in 2013. For the total population over age 16, New Mexico has the lowest labor force participation rate (57.5 percent) compared to the U.S. average of 63.2 percent and the mountain west average of 63.7 percent. For teenagers and young workers—the group aged 16 to 24—those looking for work and working were 51.2 percent of the population over age 16. In fact all of the population breakouts—for gender and race/ethnicity—show that labor force participation—and, therefore demand for labor—is weak in New Mexico.

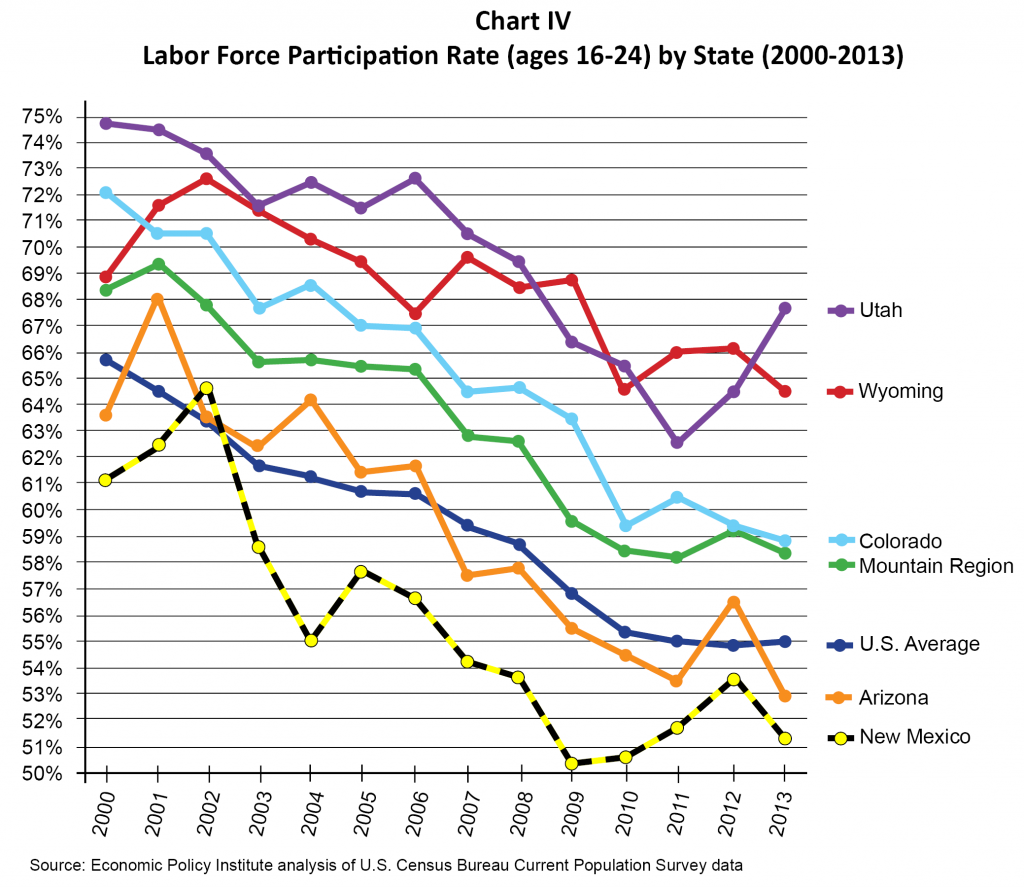

Chart IV provides a history of labor force participation for young workers by state since the year 2000. New Mexico’s labor force participation fell by 10 percentage points between 2000 and 2013, but this was a typical performance for the U.S. and the states in the mountain division. The national labor force participation rate for young workers fell by 10 points, as did the rate for the Western Region. Utah, which consistently outperforms the U.S. and the Western Region, saw a drop of only 7 points. The Wyoming labor force participation rate dropped by 4 points, Colorado fell by 13 points, and Arizona fell by about 10 points, nearly the same as New Mexico.

Employment Rates

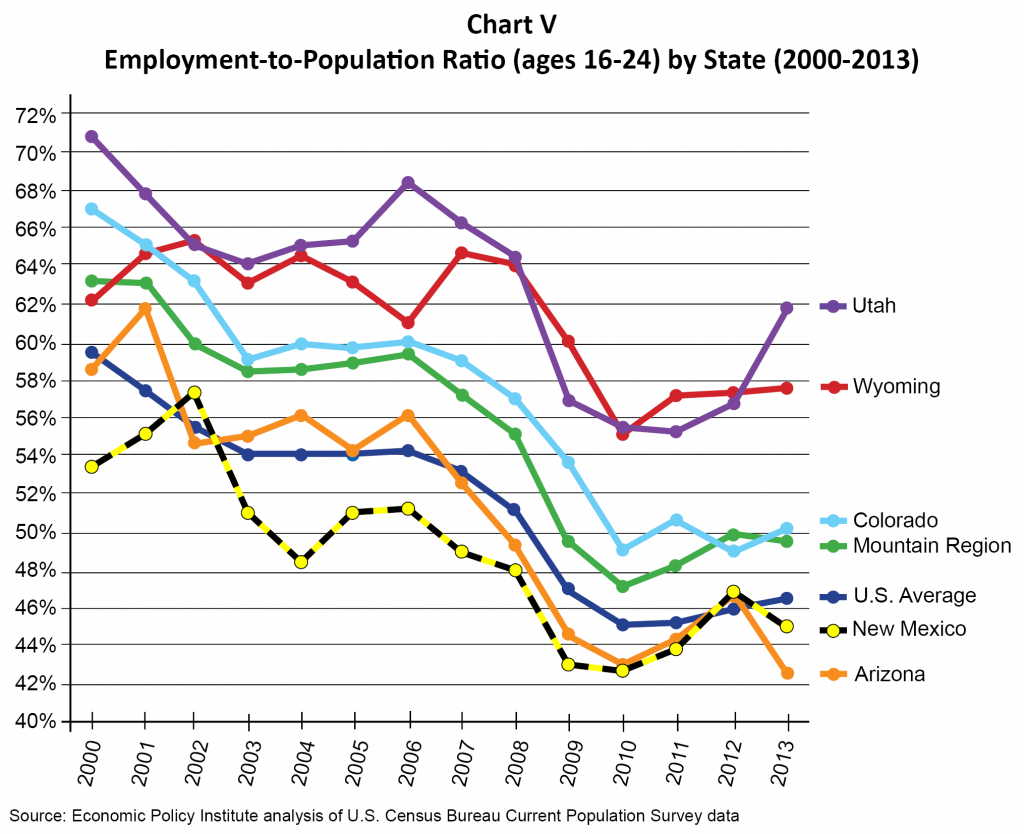

The employment-to-population ratio, or employment rate, provides an alternative measure of labor market performance and differs from the labor force participation rate in that it does not include those actively seeking work. The history of the employment rate from 2000 forward (Chart V) shows that young workers in New Mexico have fared poorly in comparison to the other states in the U.S. and the western region. It is important to note that the downward slide on the national, regional and state levels got underway before the onset of the Great Recession and has continued in the very slow recovery. The employment rate started at 53.7 percent in New Mexico in 2000 compared to the U.S. employment rate of 59.7 percent and the mountain division average of 62.8 percent. New Mexico performed worst for young workers among the mountain division states while Utah had the best performance. The downward slide in the employment rate that has taken place since 2000 is striking—the employment rate in the U.S. and western region both dropped by 13 percentage points. New Mexico’s employment rate dropped by 8 points while Colorado experienced the worst drop—almost 17 points. Although even Utah’s employment rate fell by 9 points, Utah still had the best performance in the region at 61.8 percent.

Table II, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Geographic Profiles series, allows us to look at a snapshot of the 2013 workforce with a breakout of workers aged 16 to 19. The table shows that youth have a lower labor force participation rate and employment-to-population rate than adult workers. Also, young workers have an unemployment rate about twice the average rate for all workers.

Part Time versus Full Time

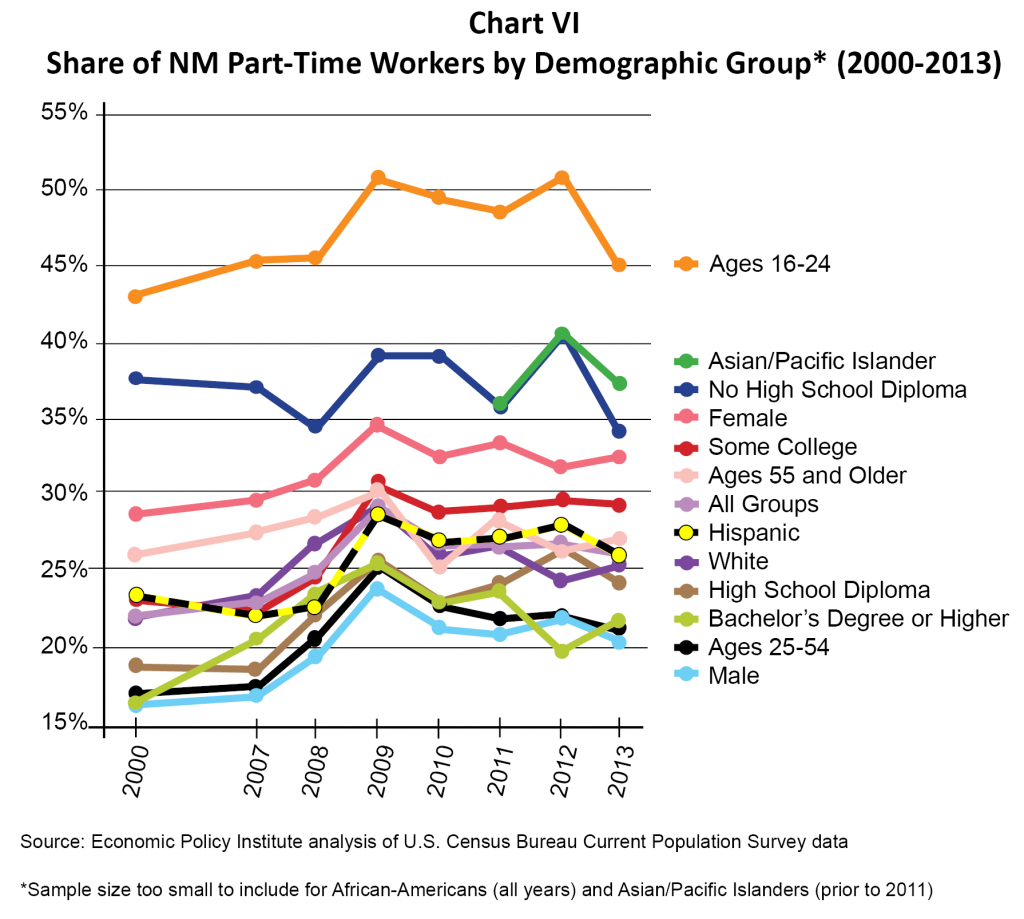

Chart VI shows that part-time workers accounted for 22.3 percent of employment in 2000, but had risen to 29 percent in 2009 at the peak of the recession. The share of part-time workers had fallen to 26 percent in 2013, which was still far higher than the share in 2000. Men worked part time at a far lower rate than women, although some of the difference could be that women choose part-time work because of family responsibilities that fall more heavily on women. Historically, teenagers and young workers work at part-time jobs at a far higher rate than older workers: the share of part-time workers in the 16 to 24 age group was 43.4 percent of total employment for the age group in 2000. The share had risen to roughly 50 percent during the recession years of 2009-2012, but fell to 45 percent in 2013. The share of part-time work for the 25 to 54 age group, the prime working age, was 17 percent in 2000, 25 percent in 2009, and 21.3 percent in 2013, still a historically high figure. Older workers—55 and older—tend to have a higher rate of part-time work, and that rate was 26 percent in 2000 and 27.1 percent in 2013. The pattern shows that the rate of part-time work has risen most (four percentage points) in the prime working age group and only slightly for young workers and older workers.

Chart VI also shows that workers with lower levels of education have higher rates of part-time work than workers with higher educational attainment: workers with less than a high school education had a 34 percent rate of part-time work, half again the rate of workers with a college degree—this group had a rate of only 22 percent.

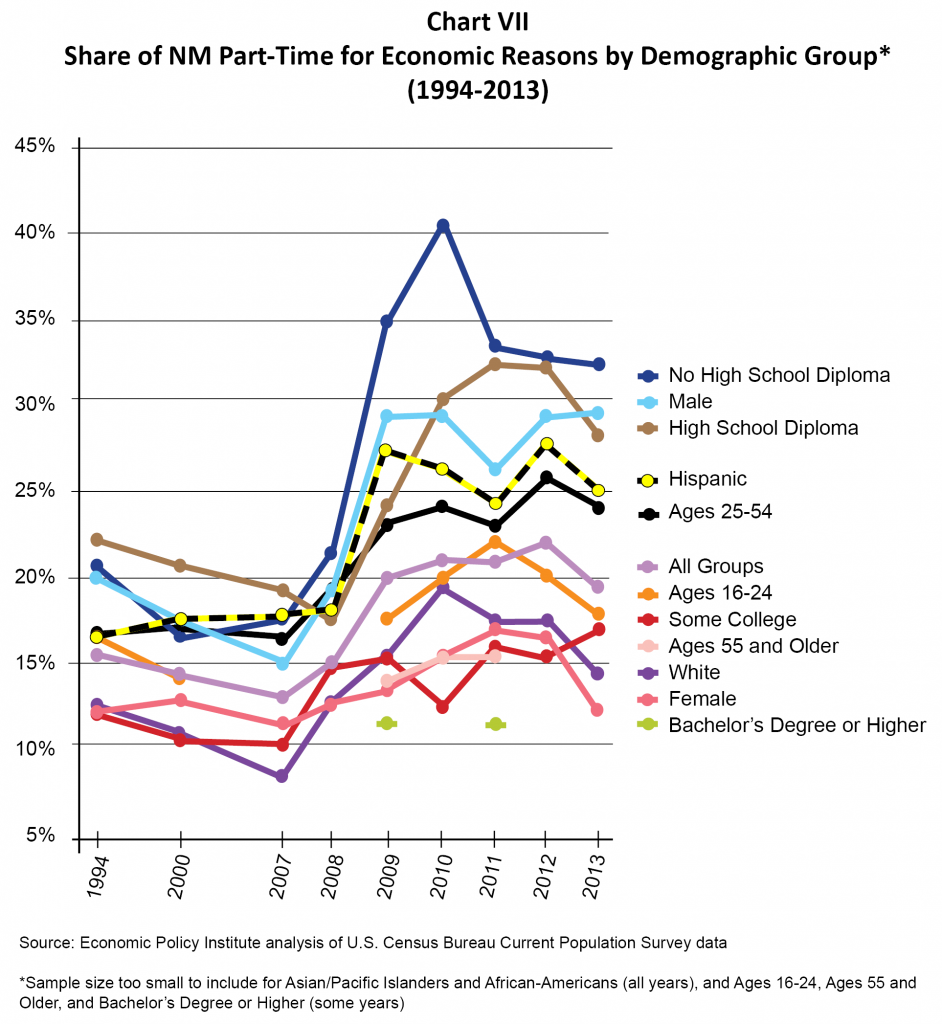

Another index of how well the state’s economy is doing is the share of part-time workers who would prefer to work full time. (Chart VII) These workers are called involuntary part-timers or “part time for economic reasons.” When many part-time workers would prefer to be working full time it is an indication of a weak demand for labor. The share of part-time workers who would prefer full-time work is trending downward. This indicator is one of the few signs that the labor market is improving in New Mexico in the wake of the recession. However, the improvement is only for women as this indicator has not yet begun to improve for men. In 2013, 12.2 percent of female part-time workers would have preferred full time work, down from 16.6 percent in 2012. For men, the 2013 figure was 29.3 percent, about the same as the 29.1 percent share in 2012.

Underemployment Rates

‘Underemployment’ includes workers who meet the official definition of unemployment as well as: involuntary part-timers; and ‘marginally attached’ workers—those who are available to work, want to work, and looked for work in the past year but have given up actively seeking work. While this is the most comprehensive measure of labor performance available from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, it does not include workers who are underemployed in a ‘skills or experience’ sense (as in, say a mechanical engineer working as a barista). Despite this limitation, underemployment reflects the reality of the labor market far better than the official unemployment rate. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics does not publish underemployment at the state level, so this measure is available only from the Economic Policy Institute (see Chart VIII).

Underemployment was at 8 percent in 2000 but reached double digits at 14 percent by 2009. Underemployment peaked at 15.6 percent in 2010 during the depths of the recession, but fell only to 13.8 percent in 2013. Underemployment for young workers followed a similar pattern, peaking at 28 percent in 2010, and falling only to 22.3 percent in 2013, still above the 18.7 percent rate in the year 2000. In other words, by 2013, New Mexico’s workers—especially young workers—had not regained the underemployment rate in 2000. The impact of the Great Recession as measured by the underemployment rate has been severe and long lasting on the New Mexico work force.

No Silver Lining

A common perception about the labor market for youth is that teenagers and young people tend to shelter in school when faced with low demand for their labor market contribution. In their recent report, The Class of 2014, the Economic Policy Institute noted that:

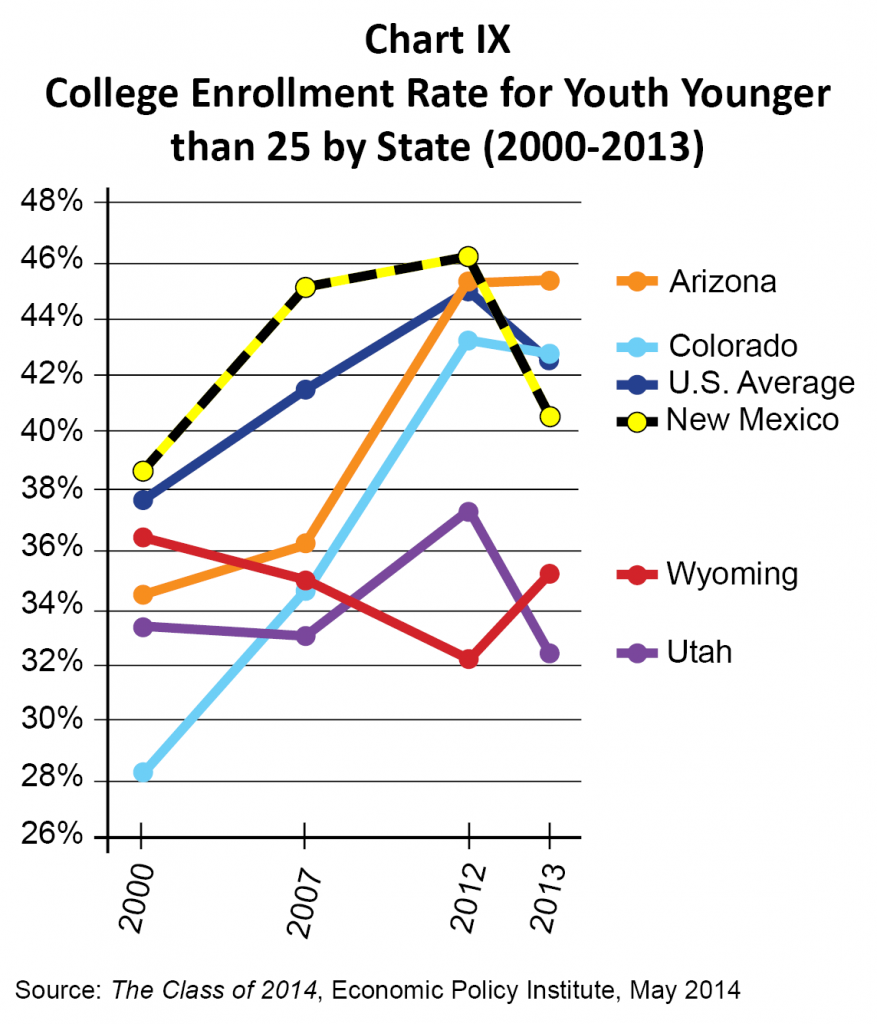

“Educational opportunity is often identified as a possible silver lining in the dark cloud of unemployment and underemployment that looms over today’s young graduates. The assumption is that a lack of job opportunities propels young people to ‘shelter’ from the downturn by attaining additional schooling. However, there is little evidence of an uptick in enrollment [for those under age 25] due to the Great Recession.”

Chart IX shows that in New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and the nation as a whole, college enrollment for youth was rising gradually between 2000 and 2007. Enrollment then dropped between 2012 and 2013, except in Wyoming and Arizona. This demonstrates that young people were not sheltering in college during the later years of the Great Recession.

Policy Recommendations

Scale up the Youth Conservation Corps to include more young people

The New Mexico Energy and Natural Resources Department manages a program called the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC). With a budget of $4.65 million, the YCC employs 800 young people to work on projects that improve New Mexico’s natural, cultural, historical, and agricultural resources. The YCC provides tuition remission for participants who complete a year in the program.

Leverage federally funded programs administered by the state

New Mexico should coordinate state policy efforts to maximize matched state funding requirements for a number of federally funded programs that have been shown to help older teens and young adults. Programs in New Mexico include: YouthBuild, a full-time paid program where young people ages 16 to 24 work on getting their high school diploma or equivalent while learning job skills as they build affordable housing in their communities; and Job Corps, an education and skills training program where at-risk and low-income young people are provided with free-of-charge housing options as they gain occupational skills and increase their educational attainment.

Increase funding and support for pre-apprenticeship and apprenticeship programs

There are several things states can do to support apprenticeship programs. Some states: provide a 50 percent discount on community college tuition for apprentices; require a 15 percent apprenticeship utilization rate on public works, transportation, and other state-funded construction projects; deploy apprenticeship consultants to help employers develop demand-driven apprenticeship programs; and/or work with contractor groups to help more women get into apprenticeship programs through job shadowing and mentorship.

Elevate the attention to issues of disconnected youth through youth advisory groups

States are required to set up Youth Councils (with various stakeholders represented) as subgroups of Workforce Investment Boards. The four Youth Councils in New Mexico should develop and disseminate state policy recommendations that are relevant to the current workforce issues and that can increase the education and employment opportunities of young persons in each of the four regions.

New Mexico’s Youth Alliance, comprised of youth representatives from every legislative district, was created to advise the Children’s Cabinet. This under-utilized resource could advise policy makers on youth participation in the workforce.

Provide more internship options for low-income young people

Subsidized internships provide low-income young adults with much-needed job experience and assistance with living expenses. Some states use Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds to subsidize employment opportunities for eligible young adults through local workforce investment agencies.

Develop a comprehensive career pathways framework

Youth with few work skills or low levels of educational attainment often need help completing high school, and earning industry-recognized credentials and college degrees. Many older teens and young adults enroll in adult basic education programs in New Mexico (about 40 percent of participants are between 16 and 24 years of age) but the state’s current system is fragmented and has low completion rates. Other states have had greater success with career pathways programs that bridge and align basic education courses with credential attainment and college courses.

Replace money diverted from the College Affordability Fund

Restoring the currently empty College Affordability Fund would provide need-based tuition assistance to those who have been out of school for more than a year and may not qualify for scholarships like the NM Lottery Scholarship. Eligibility should also be broadened to include degrees and professional certificates from two-year colleges and to allow non-traditional students to take fewer courses at a time to more easily fit school into work schedules.

Make the lottery scholarship need-based

Due to increases in tuition and a leveling-off of lottery ticket sales, the state’s lottery scholarship trust fund is in danger of being depleted. Since the eligibility criteria for the scholarship is broad—and it is available even to students who could otherwise afford the cost of college—demand remains high. Making it need-based would ensure that it was available to those who most needed it.

Increase the state minimum wage and the Working Families Tax Credit

Raising the minimum wage improves the economy because it puts money into the hands of those who are most likely to spend it—low-income workers. The state should raise the minimum wage and index it to rise with inflation. The wage for tipped workers should be raised to 60 percent of the non-tipped minimum.

Increasing the Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC) and the minimum wage together can be an effective way to encourage entrance into the work force and provide greater financial support to working families, especially those with children. The two programs overlap but reach different populations—while the minimum wage targets the lowest wage workers the WFTC reaches workers (most of whom have children) making considerably higher—but still low-wage—incomes.

Adequately fund early childhood care and learning services and K-12 education

Despite the fact that our highly technical economy has increased the demand for a better educated workforce, our educational policies have not kept up. Over the last few decades scientists have learned that 80 percent of a person’s brain development occurs during the first few years of life. Up through age four, the brain architecture that will allow for later learning is being built. When children do not receive the kind of care that supports this growth they are likely to start school already behind their peers. Remediation programs, though essential, are less effective and more costly than good prevention. While the state has increased funding for early childhood programs such as home visiting, high-quality child care, and pre-K, the need still outpaces the availability of such services.

As the recession curtailed the state’s tax revenue, deep cuts were made to spending in many programs, including K-12 education. While much of that funding has since been restored, the state is still spending less on an inflation-adjusted, per-pupil basis than before the recession.